Anti-communism in Waugh’s Sword of Honour

Ever since Tolstoy’s magisterial presentation of the battlefields in War and Peace, writers have been keen to take on the challenge of transforming the ordinarily horrific experience of war into a narrative work of scope and grandeur. The British novelist Evelyn Waugh (Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh, 1903–1966) sought to achieve something of this sort. His earlier novel, Brideshead Revisited (1945) was embedded into a wartime episode, as its subtitle indicates: The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder. But unlike that story, which sought to evoke the golden twenties, his later trilogy was indeed a wartime story. Its aim was to make sense of the Second World War in the context of a tripartite narrative.

Sword of Honour, written during the Cold War (1952–1961), was meant to provide a general account of British participation in the Second World War, with an eye to its aftermath, since the global conflict was widely seen as having strengthened communist Russia. Its author, a popular writer of the age, was himself a traditional Conservative who was nevertheless an ardent critic of the British prime minister and wartime leader, Winston Churchill. Waugh participated in the war, and his experiences led him to a pessimistic view of the leadership of the British Army, and in particular of British participation in the Balkans. He did not agree with the shift of British support from the Kingdom of Yugoslavia to Tito’s partisans in the war’s final stage. His critical attitude towards the British war effort led him to write a report directly to the government, and his literary efforts to record what happened there included—beside the later Sword of Honour—an earlier short story entitled Compassion. 11 Evelyn Waugh, ‘Compassion’, The Month, New Series 2/1 (August 1949). A shorter version

appeared as ‘The Major Intervenes’ in The Atlantic (July 1949). This enduring interest shows that Waugh was quite interested in the topic, and that besides summarizing his experiences in different literary forms, he also tried to influence events.

The hero of his magnum opus is Guy Crouchback, the son of a well-established British Catholic family. In the first two volumes he confronts absurd experiences in the army overseas and at home, comparable to those of the author. In the third book he arrives in Begoy, a fictional city in Yugoslavia, where he almost comes into open conflict with the political line followed by the political and military

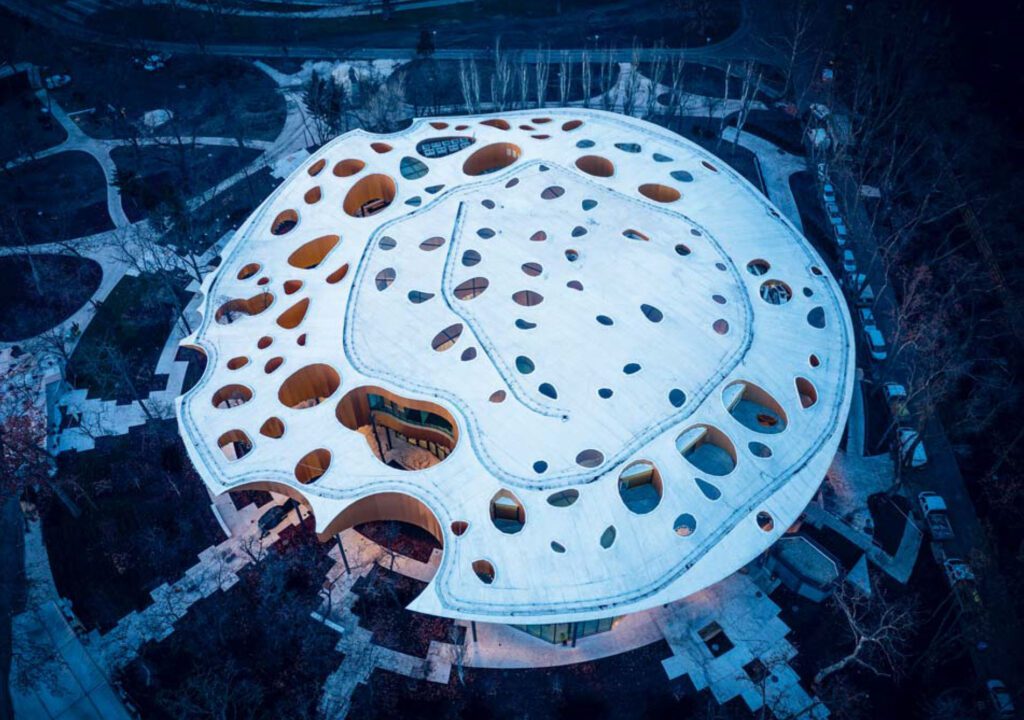

Mohai

leaders of the local forces. His most important endeavour during his mission is to defend a small group of Jewish refugees, whose fate is of no interest to the major players in a rather complex military situation. This episode has important thematic overtones—the fate of these Jewish prisoners shows the catastrophe of the Holocaust in miniature, and suggests a moral response from a Catholic perspective. Thus, the novel gives readers a glimpse into the depths of the war and its fatal consequences for most Central and Eastern European Jews, whether they fled the Nazis or were rounded up by them.

Yet Waugh also uses this narrative plot to show that the British Army did little to hinder this catastrophe. His narrative reveals the moral failure of the Brits who supported Tito’s communist policies. Crouchback, like Waugh himself at the time, tries to convince the British military commanders that they should object to the anti-Catholic measures of Tito’s partisans. In what follows I concentrate on these two episodes—the group of Jewish prisoners, and the anti-Catholic attitude of Tito’s partisans—to show that the war created a special form of human guilt and human victimhood. Waugh succeeds in presenting these two episodes both as small-scale representations of the real historical events of this phase of the war, and also as proofs that on a metaphysical level the operation of grace leaves its traces on human history.

THE RELIGIOUS DIMENSION OF THE STORY

Waugh is among those British writers with a particularly close relationship to Christianity, and in particular, to Catholicism. In this respect he resembles contemporaries like Hugh Belloc, G. K. Chesterton, Graham Greene, J. R. R. Tolkien, and C. S. Lewis. He was converted to Catholicism as an adult, which adds a special flavour to his devotion. It is interesting, however, that his refined, satirical, often sardonic style appears to be in contradiction with his Catholic background.

Take, for example, Sword of Honour. It is also written in this sardonic tone—which is quite an achievement in the case of a war novel. If there is a religious dimension to the narrative, it is hidden behind the satire, an exceptional stylistic achievement. Let us see how he builds up, step by step, this layer of the narrative. I refer here only to two of the most obvious motifs to show how the writer prepares the ground: first, the way he introduces his hero’s mission, and second, the ‘sword of honour’ itself as a key motif of the book.

The first is the background the narrator paints behind Crouchback’s decision to take up arms in defence of his country. Guy serves more or less as an alter-ego to the author, but some elements of his background are significantly different. These differences may have a certain narrative function: they provide the underlying thematic meaning behind the story.

When the war breaks out, Guy is living in Italy, at a family estate. It was established by his grandparents, Gervase and Hermione, who had first set foot on this shore after consummating their marriage on board a ship. This is how Waugh summarizes the estate’s foundation: after the event, at dawn, Gervase came on deck. He ‘called Hermione to join him and so standing together hand-in-hand, at the moist taffrail, they had their first view of Santa Dulcina delle Rocce and took the place and all its people into their exulting hearts’.22 Evelyn Waugh, Sword of Honour (Penguin Classics, 2001), 4. There they built their family home, known to the locals as ‘Castello Crauccibac’, a building which served as background to the modern history of the family, a ‘place of joy and love’.33 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 6.

It is here that Guy Crouchback withdrew after the failure of his own marriage, and it is from here that he leaves to participate in what turns out to be the Second World War. When he says good-bye to all the local dignitaries, his last visit is to the tomb of a local hero, Roger of Waybroke, an English knight. The knight lost his life here on his way to the Holy Land, at the time of the Second Crusade, in a local fight, in which he took part after being shipwrecked on his voyage from Genoa, ‘a man with a great journey still all before him and a great vow unfulfilled’.44 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 9. ‘Guy feels a particular kinship with ‘il Santo Inglese’. Now, on his last day, he makes straight for the tomb. ‘Sir Roger, pray for me’, he says, ‘and for our endangered kingdom.5’5 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 9. On the same day he also goes to confess, in order to prepare properly for the mission of participating in the defence of his country. This episode frames the whole narrative, lending it a religious meaning: the main hero’s own—somewhat unheroic—fate is to be interpreted in the light of the crusader knight, who had the bad luck to die before reaching the battlefield in the Holy Land. With this element of the story Waugh creates a parallel between the two historical epochs—a satirico-religious dimension. This is in accordance with the writer’s original intention from 1949, that his fiction would be ‘a study of the idea of chivalry’.66 Douglas Lane Pathey, Life of Evelyn Waugh: A Critical Biography (Oxford: Blackwell, 1998), 303.

A second element to confirm this parallelism—that of the metaphorical, religious dimension, above the events of the world war—is the object which gives the trilogy its name, the publicly exhibited sword of honour. This sword was exhibited in Westminster Abbey on 29 October 1943, as a present from the United Kingdom to ‘the steel-hearted people of Stalingrad’.77 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 617. ‘[I]t had been made at the King’s command8’8 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 617. , ‘silver, gold, rock-crystal and enamel had gone to its embellishment’.99 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 617. These materials express the symbolic meaning of this royal gift: it was meant to express the fact that ‘the people were suffused with gratitude to their remote allies and they venerated the sword as the symbol of their generous and spontaneous emotion’.1010 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 617.

This is an object which would have fitted well the figure of the crusader knight. But in Waugh’s story, instead of the knight, the sword is sent to ‘Joe’ Stalin, as an expression of ‘the popular enthusiasm’ aroused by his victories.1111 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 618. The presentation of the Russian communists as the heroes of the war contrasts with the religious dimension of the framework. The figure of Joe Stalin cannot replace the medieval knight and cannot fulfil the expectations of a religious believer. He is, after all, responsible for mass murder in his own country.1212 Norman M. Naimark, Stalin’s Genocides (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010). This is why Guy Crouchback did not join the enthusiastic people queuing up to see the sword in the abbey. He was ‘unmoved by the popular enthusiasm’, ‘he was not tempted to join them in their piety’.1313 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 618. In other words, Guy’s earlier effort to understand his own participation in the war in the framework of the story of the crusader knight has obvious hermeneutic problems.

Although the war against the Nazi invaders is undoubtedly just by the tenets of the ‘just war’ theory worked out in Catholic social thought, the price to be paid by the West for victory over the National Socialists is a strategic alliance with the communist Soviet Union. This strategic coalition requires the acceptance of the Soviet propaganda machine, and transforms the Soviet totalitarian regime into a legitimate global political player. Neither Waugh nor his hero Guy Crouchback is ready to accept this price without caveats. The novel is, in fact,

nothing less than a summary of Waugh’s major objections to the communist regime, as well as against the British government’s unprincipled compromises. The third book uses two examples to show why this unprincipled compromise is a mistake: one is the fate of the Jewish refugees, who are abandoned by the Allies, which leads to the murder of their spokesperson. The second is the way the Yugoslav authorities deal with Catholic priests, who are largely of Croatian origin.

THE EXEMPLARY FATE OF THE JEWISH REFUGEES

Perhaps the most important thread of the third book of Waugh’s war novel traces the fate of the Jewish refugees. Guy Crouchback is sent to Yugoslavia, as a kind of liaison officer, to mediate between the different partners of a rather complex military state of affairs.1414 ‘Guy’s duty was to transmit reports on the military situation.’ (Waugh, Sword of Honour, 811.) This is the last phase of the war, and the British Army has already changed alliance: by then ‘Tito is their friend, not Mihajlovic.15’15 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 627. Obviously, this is a radical shift in the country’s political and military position. Yet the problem seems to be deeper for Guy. He has the impression that the British are betraying their former allies, and more than that, they are sacrificing fundamental values on the altar of a winning military strategy. The episode of the Jewish refugees, just like that of the Catholic priest, serves to illustrate the sacrifice of basic Christian European values.

By the time Waugh wrote the novel, it was accepted opinion in the West that the most serious breach of basic human values was the mass murder which we refer to as the Holocaust. The term itself, Holocaust, was first used in connection with the massacre of Armenian Christians by Ottoman forces at the end of the nineteenth century.1616 David M. Crowe, The Holocaust: Roots, History, and Aftermath (Boulder, CO: Westview Press,

2008), 1. Yet at the time of the Second World War it came to mean the wilful and planned extermination of the majority of the European Jewish population by the German Nazis and their allies. Waugh, whose own thought is said to have had anti-Semitic overtones,1717 David Bittner, Evelyn Waugh and the Jews, MA Thesis (Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton,

April 1989). in this novel succeeds in showing through the fate of the Jewish refugees not only the inhuman nature of Nazi rule but also the disregard of human suffering characteristic of the warring parties, including the exclusive focus of the British high command on military utility. The plotline of the Jewish refugees also shows the survival of anti-Semitic prejudices among the major European powers, as well as among the communists. This inexplicable and tragic story is important for Waugh as a Christian writer. The ill fortune of the Jews amounts to a cultic action of imitatio Christi—the destruction of a whole group of innocents, following the pattern of Christ’s crucifixion.

When the Jewish prisoners appear in the story, they are presented in a manner akin to the choir in ancient Greek drama—they are a closely-knit community of people, united into one body, embodied by their speakers, most importantly, by the ‘woman of Fiume married to a Hungarian engineer’.1818 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 814. The members of this group are distinguished from their environment by a ‘bourgeois civility19’19Waugh, Sword of Honour, 814. , and Guy has problems in understanding their actual social status in Begoy, the fictional British headquarters in Yugoslavia. In fact, it takes time until Guy’s sense of responsibility and compassion awakens. It is the fact that Guy can speak with Mme Kanyi in Italian, his second mother tongue, that establishes between the two of them a certain, almost secret sense of linguistic community, an intimacy which helps him to see things from her perspective. She explains the prior history of the group—of which the key fact is that most of them are ‘survivors of an Italian concentration camp on the island of Rab’.2020 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 815. Most of them were ‘Yugoslav nationals’, but ‘some, like herself, were refugees from Central Europe’.2121 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 815. We learn from her that when the king departed, ‘the Ustachi began massacring Jews’.2222 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 815. To save them, the Italians took the Jews with them. Later Tito’s partisans took them back to the coast, then to the mainland, selected those who were able to work, and imprisoned the rest. After escaping the German counterattack, the partisans took the Jews to Begoy.

This short overview of the tale of woe of the group of Jews in Waugh’s novel is meant to communicate something more than the individual case. The community’s Calvary is a powerful illustration of the metaphysical significance of the war. The Jews are suffering here for the whole human community—in this sense they imitate together, as one body, the suffering of the crucified God of the Christians. Step by step Guy becomes involved in their story, and saving the group becomes a test case of whether there was any well-founded reason for him to have partaken in the war. As Waugh puts it, Guy ‘felt compassion: something less than he had felt for Virginia and her child [his ex-wife and her child] but a similar sense that here again, in a world of hate and waste, he was being offered the chance of doing a single small act to redeem the times’.2323 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 835. With this last reference, to ‘a single small act to redeem the times’ the narrator refers back to a letter from Guy’s father, which had a major impact on him, because ‘To Guy his father was the best man, the only entirely good man, he had ever known’.2424 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 674. In that letter, ‘which he carried always in his pocketbook’, his father gave him the advice to attempt small, individual acts of salvation.2525 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 754. Here is a part of that letter: ‘The Mystical Body doesn’t strike

attitudes or stand on its dignity. It accepts suffering and injustice … Quantitative judgements

don’t apply.’ When he adopts Virginia’s child after her death, Guy also recalls his father’s letter:

‘Quantitative judgements don’t apply. If only one soul was saved, that is full compensation for any

amount of “loss of face”.’ Waugh, Sword of Honour, 786. Guy’s own deeds aim to be in line with this advice, but most of the time turn out to be futile. Even if there are moments when Guy thinks he is the Moses of this group, his intention to save the Jews, and in particular their spokesperson, Mme Kanyi, fails: they end up behind the wire, and Mme Kanyi is killed by the partisans, accused of sustaining an unacceptable relationship with a British officer, Guy himself. There is no way to involve oneself directly in the workings of grace: what must happen will happen, no matter how humans wish to mitigate its sledgehammer. But this is not yet the end of the story.

GUY CROUCHBACK IN THE HANDS OF WOMEN

It is not by chance that the narrator compares Guy’s relationship to Mme Kanyi to the one which connects him to Virginia. Although Guy’s marriage failed due to the infidelity of his wife, their reunion marks the peak of the novel. Virginia appears for most of the trilogy to be a lost soul, but at the end the reader learns to esteem her.

Guy’s generous act to accept her child as his own is indeed that small act to redeem the times. The couple’s fate leads the reader from despair to a certain kind of eschatological hope. Waugh’s art of writing is at its best when the narrative transforms this uncouth and unsophisticated woman into one of the most likeable characters of the novel. The genre of the novel allows the unexpected and improbable to happen. This is where the historical dimension can connect to the metaphysical: what is hard to explain in the context of historical reality might be much easier to comprehend in the context of the eternal and the divine, which is by definition beyond human understanding, yet still potentially an important novelistic dimension. Guy’s relationship with Virginia is not the only one he has with women. Guy Crouchback is presented as a somewhat grey personality. And yet he has that human quality which allows others, particularly women, to trust him. Waugh’s women have a special talent to sense this sort of trustworthiness, and although Guy’s character has an element of the everyday loser, they find in him something else: a reliable and helpful nature. In fact, Guy’s relationship with these women reveals that there is something extraordinary in this otherwise ordinary individual.

Waugh is able to connect Guy’s character to his Catholic belief. To be sure, it is not his masculine sex appeal, but rather a trustworthiness rooted in his Christian faith, which attracts women to him. This female sensibility, which reveals Guy’s own direct connection to the divine, can be traced back to the patron saint of the settlement in Italy where the castello of Guy’s family stands: Santa Dulcina. The name of the Italian commune is also the name of one of the saints of the church. Santa Dulcina turns out to be Guy’s personal patron saint. The relationship between them reminds us of the relationship between Cervantes’s Dulcinea and Don Quixote. Both of these women called Dulcinea are absent from the life of their respective heroes, and exercise their influence indirectly, through the specific attachment they show towards their heroes, as a response to those heroes’ sensibility towards the divine.

THE ORDINARY AND THE SAINTLY IN GUY’S CHARACTER

While Guy serves as an alter ego of the author, he is also a representative of the majority of humankind, confronting the challenges of wartime. He is a modern

equivalent of Everyman, the famous title character of the medieval morality play. His character connects not only to the symbolic dramas of the Middle Ages, but also to John Bunyan’s 1678 Christian novel, The Pilgrim’s Progress: it is an allegory of the human condition. Waugh’s novel is also an allegory of human life. What he is most interested in is the quest for human salvation. At first sight, the middle of a war seems to be quite an unsuitable time for this quest. This explains Guy’s sustained effort to understand his own cause as that of a latter-day English knight—he wants to turn the brutal mass murders of his time into a chance for salvation.

Everyman embodies humankind—he is not exceptional, unlike the heroes of the ancient Greek drama. Guy Crouchback needs to be essentially average in order to represent humankind on the symbolic level of the novel. He is the ordinary human being, who tries to make sense of his or her own fate, but does not succeed easily. He is the average Englishman, who did not distinguish himself before the war broke out. In fact, he was not much more than a lost soul. He is middle class (in fact, a declining aristocrat), middle aged, and mediocre in a number of other ways too.

Guy’s most salient distinguishing characteristic is his Catholicism, which marks him off among his own compatriots, the British, while it fits very well into the context of his second home country, Italy. In Waugh’s earlier novel, Brideshead Revisited, Catholicism served as a stage background to the grandiose fall of the upper class in traditional British society.2626 Laura Coffey, ‘Evelyn Waugh’s Country House Trinity: Memory, History and Catholicism in

Brideshead Revisited’, Literature and History, 15/1 (2006), 59–73. In Sword of Honour the story is less sublime—the key figure is able to represent all of us, in his efforts to somehow redeem his own fragility, weaknesses, and inclination to guilt. He is left out from the most important events of the war, but his character in any case excludes the possibility of turning him into a war hero.

The emotional economy of his somewhat cool and reserved temper is close to the ennui or even nausée of the new French existentialist novels of the same period. Guy is like these French novels’ heroes: he is alienated from his own life. He calls this feeling the emptiness of one’s life.2727 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 676. Yet the question Waugh raises is not philosophical, like those of the novels by Gide, Camus, or Sartre, but theological. And unlike most of the heroes of those contemporary French novels, Guy can rely on his unwavering Catholic belief. Thus he has to face a new challenge in Yugoslavia, when he realizes how savagely the communists are persecuting Catholic priests in the territories they occupy.

WAUGH’S REPORT ON ANTI-CATHOLCISM IN COMMUNIST YUGOSLAVIA

Milena Borden dedicated a study to Waugh’s experience of the persecution of Catholics by the communist forces of Yugoslavia.2828 See also Donat Gallagher, ‘Captain Evelyn Waugh and the Special Operations Executive (SOE)’,

Evelyn Waugh Studies, 43/2. She is concerned more with Waugh’s own personal experiences, and less with the literary rendering of that experience. Her research is based on ‘Waugh’s diaries, letters, political, polemical writings and biographies of him, but most importantly, on the government report written by Waugh, and entitled “Church and State in Liberated Croatia” (30 March, 1945)’.2929 Milena Borden, ‘Evelyn Waugh’s Yugoslav Mission: Politics and Religion’, Evelyn Waugh Studies,

49/1 (Spring 2018), 2–25. In it, she claims, ‘the novelist presented documentary evidence for his concerns about the alliance of British with the Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito during the Second World War, recording the killing of 17 Catholic priests as human rights violations’.3030 Borden, ‘Evelyn Waugh’s Yugoslav Mission’. According to Waugh, the Catholic priests were killed as an act of political revenge, in preparation for the creation of an atheist, communist regime.

Waugh’s critical opposition to Churchill’s wartime policies can be explained by the difference between the politician’s and the intellectual’s point of view. While the politician’s decision is based on calculations of short-term interests, the job of the intellectual is to consider long-term interests. Churchill’s effort to win the trust of Stalin and Tito had a well-considered basis, but according to Waugh the price he was ready to pay was unacceptably high. Waugh’s situation was complicated by the fact that his partner in his mission in Yugoslavia was Churchill’s son, Major Randolph Churchill. They remained good friends even after the ‘victorious conclusion’ of the war, when Waugh’s critical objections to Churchill’s strategy were confirmed by the facts. The writer could accept Churchill’s overall aim: to keep Stalin in the alliance against the Nazis. Yet Waugh as a Catholic was able to discover what was happening behind the scenes: that the priests of the Roman Catholic Church were falling victim to communist political persecution. The blindness of the British, who had the single aim of preserving the newly gained alliance, blinded them to some realities of the political situation. The intention of Waugh’s report was not only to reveal the basic facts behind the scenes, but also to argue that the price paid was too high. ‘Waugh thought that Tito’s anti-Catholic policy should not be accepted as part of the price of the alliance to defeat the Nazis.31’31 Borden, ‘Evelyn Waugh’s Yugoslav Mission’.

There is more than one reason behind Waugh’s defence of the Croatian Catholics and their priests, and his attempt to try to convince British political decision makers of the truth. Certainly, as a Catholic, he could not be indifferent to the fate of Catholicism in post-war Yugoslavia. As a British patriot, he also had good reason to be concerned about the path British military and civil leadership took in the global arena. And as a political theorist, he was certainly right to emphasize that the victory over Nazism was not the end of the game and that communism was just as much an opponent of Christian European values as Nazism. Borden rightly claims that Waugh’s worries were well-founded: the Cold War broke out immediately after the war between the West and the totalitarian Stalinist regime. Any reader of Churchill’s Fulton speech will suspect that he himself had a bad conscience over his close alliance with Stalin.

This is Waugh, the politically active citizen and self-conscious officer of the British Army. Yet, for us the question is how this topic is elaborated in the novel within the framework of the narrative.

THE FATE OF THE CATHOLIC PRIEST IN WAUGH’S NOVEL

Unlike Waugh himself, Guy takes seriously the strict regulations in the Army, and keeps clear of politics for as long as he can. He concentrates on his simple duty, i.e. ‘to transmit reports on the military situation’.3232 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 811. Arguably, his interest in the fate of the group of Jews, and his efforts to support them, were legitimate parts of his military mission. Yet they were not welcomed by his military superiors, who repeatedly reminded him to ‘Keep clear of civilians’.3333 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 818.

Yet Guy is unable to follow this last injunction. When he hears about Virginia’s death from a V1 bomb strike on the house in London where she lived with her child, Gervase, Guy wants a mass offered in her memory. He makes the Croatian priest a present of some canned food and chocolate for doing so. However, Guy thus becomes suspect in the eyes of those watching his activities. They think he is conspiring with the priest and suspect a criminal offence. He is informed that a complaint was made against him, saying that he ‘had been guilty of “incorrect” behaviour’.3434 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 853. His old acquaintance and present boss, the secret communist De Souza, tells him that luckily the priest was not arrested ‘or worse’. This failure, which almost turned out to be fatal for the priest, reminds Guy of the fact that his efforts to perform that little good deed, of which his father spoke, have again failed. As in the case of the accusation against Mme Kanyi, this time too, the charge was occasioned by Guy himself—he caused Mme Kanyi’s tragic fate, and almost caused the same to the old priest. The priest too might have been condemned to death by the communists because of Guy’s simple request to offer a mass to the memory of his wife. Although we hear no more about the Croatian Catholic priest, this example, together with that of the story of Mme Kanyi, reveals the brutality of the newly emerging communist regime. Thus they serve to underline the political message of the novel: that it was a mistake to take the words of the communist allies seriously, and that the post-war situation would inevitably lead to a bipolar global conflict between the West and the communist world.

Guy Crouchback was unable to come out of the war as a real hero. He could not fulfil his dream of becoming a modern crusader, as he intended to, when he stood at the tomb of the medieval English knight soon after the outbreak of war. He was crushed by history. And yet, in his personal life, by accepting his wife’s return and adopting her child Gervase as his own, he was in fact able to redeem himself. Waugh’s story seems at first to be one of disillusionment: the brutal historical events of the Second World War did not allow his hero to distinguish himself. Yet if we have the patience to uncover some of the hidden dimensions of the novel, we find that, at last, grace found his hero.

CONCLUSION: WAUGH’S CATHOLIC, ANTI-TOTALITARIAN STANCE

Waugh was one of the most remarkable British Catholic writers of his age, the first half of the twentieth century, which was also the age of Chesterton, C. S. Lewis, and Tolkien. While Brideshead Revisited is usually considered his best novel, Sword of Honour is perhaps the most complex and mature of his works. It is a grand panorama of the Second World War from a British Catholic perspective. But it is neither tragic nor sublime. Instead, it is mostly satirical: an eyewitness of that horrible war, Waugh’s aim was to show how history plays its game with the individual. The novel is also a scathing criticism of the British Army and its bureaucratic structures.

Yet the satirical surface hides a more substantial theologico-philosophical substratum. Like the French existentialist novelists, or, for that matter, the authors of the medieval morality plays or absurdist dramas, Waugh is interested in the fate of the human being in the present, and in what happens to the everyday man during the upheavals of crisis and war. Although he is disillusioned and pessimistic, as many modern writers tend to be, his intricate narrative uncovers the hidden operations of grace and its effects on human life. God takes care of Guy: he remains unscathed on the battlefields, and finally finds his place in the world, in loyal service to his returned, prodigal wife by adopting her child and bringing him up as his father, after the death of the boy’s mother.

If we look at the novel from a political point of view, it turns out to be a harsh criticism of the fickle policy of Churchill’s Britain during the war. Waugh presents the shift of alliances—Britain abandoning the king of Yugoslavia in favour of Tito, the communist leader of the future Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia—as a betrayal. While Churchill, the pragmatic political leader, was ready to weigh everything from the perspective of how to defeat Nazi Germany, Waugh, the intellectual, could not help looking at the long-term effects of an alliance with communist countries like the Soviet Union or Tito’s Yugoslavia. Without Churchill’s political about-face, the British could not have played such a pivotal role in the course of the war. Yet without the perspective offered by Waugh’s narrative, we would forget the fact that there are two sorts of totalitarian rule, and the victory over one does not solve the problem of how to get rid of the other.

Waugh’s alertness to the problem of the global threat of totalitarian rule makes his novel a lasting achievement. It is specifically relevant to those societies which had direct experience of both Nazi German and communist Russian occupation. For a Hungarian reader, for instance, who was brought up before the fall of the Iron Curtain, Guy’s rejection of communism needs no explanation. Beyond the aspects mentioned above, which make Sword of Honour a remarkable moral and theological inquiry, his brilliant political insight makes Waugh the author of one of the most important historical novels of his age—a novel which turns out to be not only to have religious overtones, but also to be remarkably politically far-sighted

- 11 Evelyn Waugh, ‘Compassion’, The Month, New Series 2/1 (August 1949). A shorter version

appeared as ‘The Major Intervenes’ in The Atlantic (July 1949). - 22 Evelyn Waugh, Sword of Honour (Penguin Classics, 2001), 4.

- 33 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 6.

- 44 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 9.

- 5’5 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 9.

- 66 Douglas Lane Pathey, Life of Evelyn Waugh: A Critical Biography (Oxford: Blackwell, 1998), 303.

- 77 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 617.

- 8’8 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 617.

- 99 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 617.

- 1010 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 617.

- 1111 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 618.

- 1212 Norman M. Naimark, Stalin’s Genocides (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010).

- 1313 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 618.

- 1414 ‘Guy’s duty was to transmit reports on the military situation.’ (Waugh, Sword of Honour, 811.)

- 15’15 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 627.

- 1616 David M. Crowe, The Holocaust: Roots, History, and Aftermath (Boulder, CO: Westview Press,

2008), 1. - 1717 David Bittner, Evelyn Waugh and the Jews, MA Thesis (Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton,

April 1989). - 1818 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 814.

- 19’19Waugh, Sword of Honour, 814.

- 2020 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 815.

- 2121 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 815.

- 2222 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 815.

- 2323 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 835.

- 2424 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 674.

- 2525 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 754. Here is a part of that letter: ‘The Mystical Body doesn’t strike

attitudes or stand on its dignity. It accepts suffering and injustice … Quantitative judgements

don’t apply.’ When he adopts Virginia’s child after her death, Guy also recalls his father’s letter:

‘Quantitative judgements don’t apply. If only one soul was saved, that is full compensation for any

amount of “loss of face”.’ Waugh, Sword of Honour, 786. - 2626 Laura Coffey, ‘Evelyn Waugh’s Country House Trinity: Memory, History and Catholicism in

Brideshead Revisited’, Literature and History, 15/1 (2006), 59–73. - 2727 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 676.

- 2828 See also Donat Gallagher, ‘Captain Evelyn Waugh and the Special Operations Executive (SOE)’,

Evelyn Waugh Studies, 43/2. - 2929 Milena Borden, ‘Evelyn Waugh’s Yugoslav Mission: Politics and Religion’, Evelyn Waugh Studies,

49/1 (Spring 2018), 2–25. - 3030 Borden, ‘Evelyn Waugh’s Yugoslav Mission’.

- 31’31 Borden, ‘Evelyn Waugh’s Yugoslav Mission’.

- 3232 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 811.

- 3333 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 818.

- 3434 Waugh, Sword of Honour, 853.