You are holding in your hand one of the strangest, most vivid and glamorous of verse tales, the story of a peasant boy found among corn and therefore named Johnny Grain-o’-Corn, who from early childhood has pledged his heart to an orphan girl, the beautiful Iluska (called Nelly [or Nell for short] in the translation). But misfortune befalls them both and Johnny has to flee the village and undertake extraordinary adventures before he can find his way back to his first love. Ostensibly for children, the tale can freeze a child’s marrow as it did mine, with its horrors of battles, giants, witches, ghosts, and dragons; it can dazzle with wonderful ludicrous images such as the brave Hungarian hussars carrying their horses on their backs, or crossing mountains, eating the air and squeezing water from a cloud as they go; it can even prepare a child for the onset of romantic and sexual excitement as it does right at the beginning of the poem when Johnny’s heart beats faster at the sight of Iluska’s swelling bosom and slender waist.

This complex dish is served up with a garnish of irony, nonsense, and good humour that can laugh at itself and play havoc with geography, and enough bloodthirstiness and cruelty to launch a thousand corpses. The telling of the tale is accomplished with such brio you cannot help but be swept along by it, even while noticing that the underside of the story is steeped in melancholy and death. The world Sándor Petőfi deals with is violent, magical, and utterly perilous. My own childhood’s first understanding of love, terror, gold, silver, seas and storms, monstrosities, wickedness, and fierce resolutions was rooted in this wonderful journey, as were many children’s before and after mine. Love, fidelity, courage, and wit are the victors. To an adult, the red hussar’s uniform, the warrior’s rusty sword, the red rose at the heart of the lake may serve as the scarlet relics of a breathless childhood delight. The tale is enchantment: ghost train and big dipper combined. To render the original justice is an order as tall as the gate of the giants’ castle in the twentieth episode, but John Ridland has set about the task with energy and delight—the only possible way. He has hitched his horse to Petőfi’s restless wagon, so we too may go bounding gratefully along.

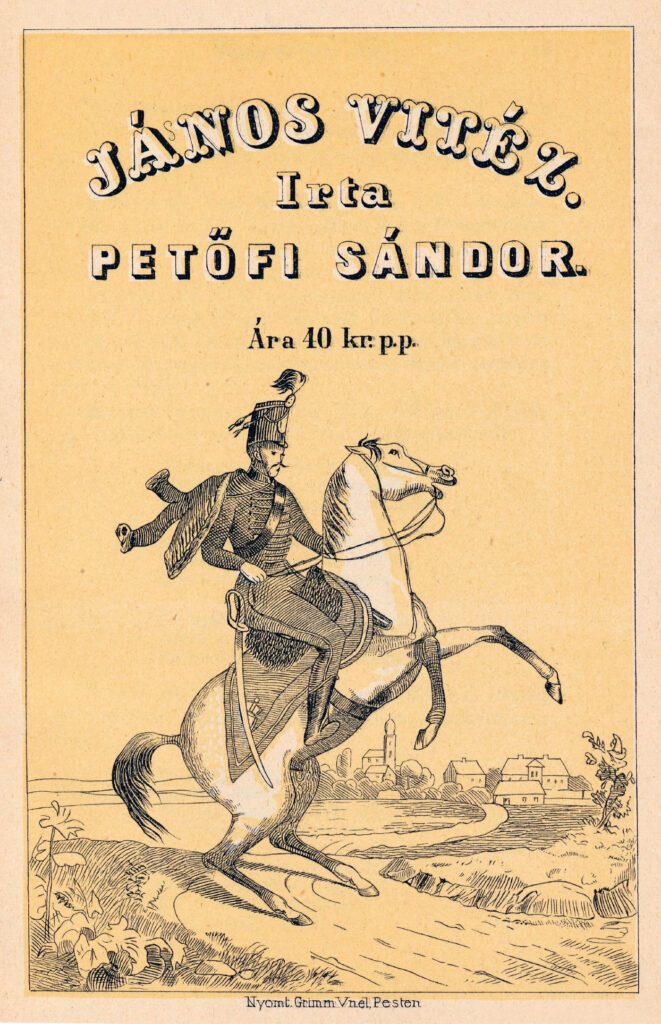

Grimm (1801–1872)

[7]

Johnny’d been to the Back of Beyond, and by then

He gave scarcely a thought to the dead bandits’ den;

Now in front of him suddenly something was gleaming,

Some weapons, off which the sun’s arrows were beaming.

Magnificent hussars approached him, astride

Magnificent steeds, shining swords by their sides;

Each proud charger was shaking its delicate mane

And stamping and neighing in noble disdain.

As he saw them draw near him in all of their pride,

Johnny felt his heart swell up to bursting inside,

For here’s what he thought: “If they only would take me,

A soldier indeed I gladly would make me!”

With the horses on top of him nearly, he heard

Their leader yell out at him this warning word:

“Fellow countryman, watch it! you’ll step on your head …

What the devil so fills you with sorrow and dread?”

Johnny answered the captain in one pleading breath:

“I’m an exile who wanders the world till my death;

If you’d let me join up with your worships, I think

I could stare down the sun with nary a blink.”

Said the officer: “Think again, friend, if you will!

We’re not going to a party, we’re marching to kill.

The Turks have attacked the good people of France;

To the aid of the Frenchmen we make our advance.”

“Well sir, war won’t make me the least little bit sad;

Set me onto a saddle and horse, I’ll be glad —

Since, if I can’t kill someone, my sorrow will kill me,

Fighting’s the lifework that most will fulfill me.”

“It’s true, I could only ride donkeys to date,

Since the lot of a sheepherder’s been my hard fate.

But a Magyar I am, God made us for the horse,

And made horses and saddles for Magyars, of course.”

Johnny spoke a great deal as he let his tongue fly,

But he gave more away with his glittering eye;

It’s no wonder the leader should quickly contrive it

(He took such a liking) to make him a private.

You’d have to invent some quite elegant speeches,

To tell how Johnny felt in his bright scarlet breeches,

And how, when he’d slipped on his hussar’s red jacket,

He flashed his sword up at the sun, trying to hack it.

His bold steed was kicking up stars with its shoes,

As it bucked and reared, hoping to bounce Johnny loose,

But he sat on it firm as a post, and so tough,

An earthquake could never have shaken him off.

His soldier companions soon held him in awe,

When his strength and his handsome appearance they saw,

In whatever direction they marched and took quarters,

When they left, tears were shed by the whole region’s daughters.

But none of these young women mattered to Johnny,

Not one of them ever appeared really bonny

Though he travelled through many a land, truth to tell,

He nowhere found one girl the equal of Nell.

[8]

Now slowly, now quickly, they marched in formation,

Till they came to the heart of the Tartary nation;

But here a great peril awaited: toward

Them, the dog-headed Tartars advanced in a horde.

The dog-headed Tartars’ commander-in-chief

Barked out to the Magyars his challenge in brief:

“Do you think you can stand against us and survive?

Don’t you know that it’s man-flesh on which we thrive?”

At this the poor Magyars were shaking with fear,

As they saw many thousands of Tartars draw near;

They were lucky that into that countryside came

The Saracen king, of benevolent fame.

He instantly sprang to the Magyars’ defense,

Since he’d taken a journey through Hungary once,

And the friendly, good-hearted Hungarians then

Had seemed to that Icing the most decent of men.

The Saracen had not forgotten it since,

Which is why he stepped up to the fierce Tartar prince,

And with these kindly words he attempted to bend

To the cause of the Magyars his good Tartar friend:

“Dear friend of mine, pray, meet these soldiers in peace,

They will do you no injury, none in the least,

The Hungarian people are well known to me,

Please grant me this favor and let them pass free.”

“Well I’ll do it, but only for you, friend, alone,”

The head Tartar said in a mollified tone,

And what’s more, wrote a safe conduct pass for their group,

So that no one would trouble the brave Magyar troop.

It is true that they met with no fuss or disorder,

But still they rejoiced when they came to the border,

How not rejoice? Tartar land’s too poor to dig,

Yielding nothing to chew on but bear meat and fig.

[9]

The hills and the hollows of Tartar terrain

For a long time gazed after our troop’s little train,

Indeed they were now well inside Italy,

In its shadowy forests of dark rosemary.

Here nothing unusual needs to be told,

Except how they battled against the fierce cold,

Since Italy’s always in winter’s harsh vise;

Our soldiers were marching on sheer snow and ice.

All the same, though, the Magyars by nature are tough,

Whatever the chill, they were hardy enough;

And they thought of this trick: when it got a bit colder,

Each dismounted and carried his horse on his shoulder.

[10]

They arrived in the land of the Poles in this way,

And from Pole-land they rode through to Indi-ay;

France is the nearest of lndi-ay’s neighbors,

Though to travel between them’s the hardest of labors.

In Indi-ay’s heart you climb hill after hill,

And these hills pile up higher and higher, until

By the time that you reach the two countries’ frontier,

Up as high as the heavens the mountain peaks rear.

At that height how the soldiers’ sweat rolled off,

And their capes and neckerchiefs, they did doff …

How on earth could they help it? the sun, so they said,

Hung just one hour’s march above their heads.

They had nothing at all for their rations but air,

Stacked so thickly that they could bite into it there.

And their drink was peculiar, it must be allowed:

When thirsty, they squeezed water out of a cloud.

At last they had climbed to the top of the crest;

It was so hot that traveling by night was the best.

But the going was slow for our gallant Magyars:

Why? Their horses kept stumbling over the stars.

In the midst of the stars, as they shuffled along,

Johnny Grain-o’-Corn pondered both hard and strong:

“They say, when a star slips and falls from the sky,

The person on earth whose it is — has to die.”

“How lucky you are, my poor Nelly’s stepmother,

That I can’t tell one star up here from another;

You would torture my dove not a single hour more —

Since I’d kick your detestable star to the floor.”

A little while later they had to descend,

As the mountain range gradually sank to an end,

And the terrible heat now began to subside,

The further they marched through the French countryside.

[11]

The land of the French is both splendid and grand,

Quite a paradise really, a true Promised Land,

Which the Turks had long coveted, whose whole intent

Was to ravage and pillage wherever they went.

When the Magyars arrived in the country, that day

The Turks were hard at it, plundering away,

They were burgling many a precious church treasure,

And draining each wine cellar dry at their pleasure.

You could see the flames flaring from many a town,

Whoever they faced, with their swords they cut down,

They routed the French king from his great chateau,

And they captured his dear only daughter also.

That is how our men came on the sovereign of France,

Up and down he was wandering in his wide lands;

The Hungarian hussars, when they saw the king’s fate,

Let fall tears of compassion for his sorry state.

The fugitive king said to them without airs:

“So, my friends, isn’t this a sad state of affairs?

My treasures once vied with the treasures of Darius,

And now I am tried with vexations so various.”

The officer answered encouragingly:

“Cheer up, your royal Majesty!

We’ll make these Ottomans dance a jig,

Who’ve chased the King of France like a pig.”

“Tonight we must take a good rest and recoup,

The journey was long, we’re a weary troop;

Tomorrow, as sure as the sun shall rise,

We will recapture your territories.”

“But what of my daughter, my darling daughter?

The vizier of the Turks has caught her …

Where will I find her?” The French king was quaking;

“Whoever retrieves her, she’s yours for the taking.”

The Magyars were stirred to a buzz by this speech,

And hope was aroused in the heartstrings of each.

This became the resolve in every man’s eye:

“I shall carry her back to her father or die.”

Johnny Grain-o’-Corn may have been wholly alone

In ignoring this offer the French king made known;

For Johnny’s attention was hard to compel:

His thoughts were filled up with his beautiful Nell.

[12]

The sun, as it will do, rose out of the night,

Though it won’t often rise to behold such a sight

As now it beheld what the day brought to birth,

All at once, when it paused on the rim of the earth.

The troopers’ loud trumpet call piercingly rang out,

At its shrill proclamation the soldiers all sprang out;

They ground a keen edge on their sabers of steel,

And they hurriedly saddled their horses with zeal.

The French king insisted on his royal right

To march with the soldiers along to the fight;

But the hussars’ commander was canny and wise,

And offered the King this hard-headed advice:

“Your Majesty, no! it is better you stay,

Your arm is too weak to be raised in the fray;

I know, time has left you with plenty of grit,

But what use, when your strength has departed from it?”

“You may trust your affairs to us and to God;

I’ll wager, by sunset myself and my squad

Will have driven the foe from the lands that you own,

And your highness will sit once again on your throne.”

The Magyars leapt onto their steeds at his order,

And started to hunt out the Turkish marauder;

They didn’t search long till they came on their corps,

And by means of an envoy at once declared war.

The envoy returned, the bugle call sounded,

And the terrible uproar of battle resounded:

Steel clanged against steel, while a wild yell and a shout

Were the fierce battle cry that the Magyars sent out.

They dug in their spurs for all they were worth,

And their steeds’ iron shoes drummed so hard on the earth,

That the earth’s heart was quaking down deep in its fold,

Out of fear of the storm that this clamor foretold.

A seven-tailed pasha was the Turkish vizier,

With a belly as big as a barrel of beer;

His nose was rose-red from drafts without number,

And stuck out from his cheeks like a ripened cucumber.

Well, this potbellied vizier of the Turkish troops

At the battle call gathered his men into groups;

But his well-ordered squads halted dead in their tracks,

At the first of the Magyar hussars’ attacks.

These attacks were the real thing, and not children’s play,

And suddenly terrible chaos held sway,

The Turks were perspiring with blood in their sweat,

Which turned the green battlefield ruddy and wet.

Hi-dee-ho, what a job! our men piled them up deep,

Till the corpses of Turks made a mountainous heap,

But the big-bellied pasha gave out a huge bellow,

And leveled his weapon at Johnny, poor fellow.

Johnny Grain-o’-Corn didn’t take this as a jest,

At the great Turkish pasha with these words he pressed:

“Halt, brother! you’ve far too much bulk for one man;

I’m going to make two out of you if I can.”

And he acted then just as he said he would do,

The poor Turkish pasha was cloven in two,

Right and left from their sweat-bedecked steed they were hurled

And in this way both halves took their leave of this world.

When the timorous Turkish troops saw this, they wheeled,

And yelling, “Retreat!” the men took to their heels,

And they ran and they ran and might be on the run

To this day, if the hussars had not chased them down.

But catch them they did, and they swept like a mower,

The heads fell before them, like poppies in flower.

One single horse galloped away at full speed;

Johnny Grain-o’-Corn chased after him on his steed.

Well, the son of the pasha was galloping there,

Holding something so white on his lap and so fair.

That whiteness in fact was the princess of France,

Who knew nothing of this, in a faint like a trance.

Johnny galloped a long while until, alongside,

“Halt, by my faith!” was the challenge he cried.

“Halt, or I’ll open a gate in your shell,

Through which your damned soul can go gallop to Hell.”

But the son of the pasha would never have stopped,

Had the horse underneath him not suddenly dropped,

It crashed to the ground, and gave up its last breath.

The pasha’s son pleaded, half frightened to death:

“Have mercy, have mercy, oh noble-souled knight!

If nothing else moves you, consider my plight;

I’m a young fellow still, life has so much to give …

Take all my possessions, but allow me to live!”

“You can keep your possessions, you cowardly knave!

You’re not worth my hand sending you into your grave.

And take this word back, if you’re not too afraid,

This will show how the sons of marauders are paid.”

Johnny swung from his horse, to the princess advanced,

And into her beautiful blue eyes he glanced,

Which the princess in safety had opened up wide,

To his questioning gaze now she softly replied:

“My dear liberator! I don’t know who you are,

I can tell you, my gratitude ought to go far.

I’d do anything for you, in thanks for my life,

If you feel so inclined, you can make me your wife.”

Not water but blood in our Johnny’s veins flows,

In his heart an enormous great tussle arose;

But his heart’s mighty tussle he was able to quell,

By bringing to mind his Iluska — his Nell.

He spoke thus with kindliness to the princess:

“My dear, let us do what we ought, nothing less:

We must talk to your father before we decide.”

And he chose to walk back with the girl, not to ride.

Translation by John M. Ridland