On Hungary’s National Palace and Castle Programmes

Whether walking the streets of Budapest, especially in the Castle District, admiring the main squares of Hungarian towns and cities, visiting the countryside, or watching the renovation of former aristocratic castles and the ‘reconstruction’ of ruins which were once castles, it is apparent even to the outside observer that there has been a frenzy of restoration work in Hungary. Many look on this with satisfaction, while others, especially monument protection experts, view it with considerably greater scepticism, arguing that those who undertake such large-scale projects often do not possess true expertise in preserving historical, architectural, and art-historical value. Sometimes only the original facade is preserved, while the building behind it is demolished to make room for a design more suited to modern needs. Elsewhere, historicizing renovation and reconstruction work seek to give the appearance of originality while artificially evoking the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. And not only on plots left empty after the violent destruction of the Second World War and the subsequent tearing down of damaged buildings, but also on the sites of houses built in the second half of the last century, which, though often considered iconic by the architectural community, are now abruptly being earmarked for demolition.

In fifty years’ time we can be sure everyone will believe that buildings constructed from modern materials with a historical facade are all original; indeed, even today, many are already inclined to make this assumption. Just as elsewhere in the world and at other times, architecture has a way of generating debates—at times heated, at times restrained—so in Hungary there is now an agreed battlefield for this recurrent dispute, and that is the restoration of castles.

How it all began

The castles of Hungary, the vast majority of which were built during the second half of the nineteenth century on top of earlier foundations, and acquired their present form at the beginning of the twentieth century, suffered a sad fate after the Second World War. As for their owners, the Hungarian nobility, some fled abroad during the war, and those who remained and tried for a time to integrate into the new social order first lost their land to nationalization, then their castles.

National Heritage Protection and Development Non-profit Ltd.

The vast majority of more than 1,500 castles and mansions in the country were damaged and looted by the state, along with almost 8,000 cadastral acres of gardens and parks. During the final stages of the war, the buildings left behind were often looted in quick succession by retreating German and advancing Soviet troops, and the rest fell prey to the locals. The rich libraries and archives, which may have told the history of the owner’s family and the castle’s construction, were lost. The collections of paintings and sculptures, antique furniture and utensils, fared no better. A few pieces made it to museum collections, almost by chance, while others remained in place only because they were too bulky or heavy to move. Then nationalization produced still more unhappy circumstances: these buildings were used as emergency apartments, military hospitals, barracks, children’s shelters, offices, factories, or warehouses, or else the production cooperative used the ornate drawing rooms, for lack of any better function, as a grain store, or a depot for tractor trailers. In one case a neurological institute was established within a castle. It was not uncommon for the parquet to be ripped up, sometimes to be replaced with linoleum, at other times not replaced at all.

Even very well-built houses could not withstand the ravages of time and irresponsible, careless use. The houses decayed, the plaster crumbled, the murals faded, the patios became cracked and overgrown, the roof structure collapsed, and leaks became an everyday occurrence. All traces of the former beauty of the parkland surrounding the castles soon disappeared. Often they were broken up, and public roads were laid across them.

RESCUE … BUT HOW?

It was not until the 1980s that these architecturally important buildings entered the general discourse, and by then they were in an advanced state of decay; while they were often given protected heritage status, it was only rarely possible to conduct work to at least stabilize the condition of the buildings. Under a 1981 government decree, a programme for the renovation and utilization of endangered castles and the rescue of historical buildings was established, which managed to slow the rate of decay, but proved insufficient to halt, let alone reverse it.

Questions of what should be done with state-owned castles, who should care for them and how, whether they could be privatized, and if so, whether any buyer or investor could be found who would accept the horrendous costs and—naturally—stringent heritage restrictions, therefore became increasingly acute.

The year 1992 arrived, and with it a law placing the protection of heritage buildings under the competence of the National Office for the Protection of Monuments, and appointing the State Preservation Board of the Monuments, in line with other international examples, as the custodian of monuments which were to remain permanently state-owned, a category made up predominantly of castles. During the first two years, only the Grassalkovich Castle in Gödöllő came under the protection of the Preservation Board, which began to develop a programme for its restoration, exhibitions, and presentation, all of which meant that, as an irony of fate, the Gödöllő Castle ultimately fell outside its purview. In its place, the Preservation Board became responsible for the Fáy Castle in Fáj, the Károlyi Palaces in Fehérvárcsurgó and Füzérradvány, the Nádasdy Castle in Nádasdladány, the Ráday Castle in Pécel, and the De la Motte Palace in the Buda Castle District. From 2004, it likewise became responsible for the Festetics Castle in Dég, the L’Huillier–Coburg Castle in Edelény, the Esterházy Palaces in Fertőd and Tata, the Lónyay Castle in Tuzsér, the Zichy Castle in Fertőrákos, the Károlyi Castle in Szegvár, the Cziráky Castle in Lovasberény, the Camaldolese Hermitage in Majk, the Episcopal Palace in Sümeg, and the Becsky–Kossuth Manor in Komlódtótfalus. The principal task at the time was to furnish them with historical furniture and objects, in order to present these houses as aristocratic residences, or to create a new function for them as event venues.

© Zoltán Kovács / National Heritage Protection and Development Non-profit Ltd. (NÖF)

From the beginning of the 2000s, a series of castle programmes of varying scope took possession of properties which had not been brought under state heritage protection. The programmes included one which sought to bring castles into the international tourist circuit, one which planned to turn them into luxury hotels, and another that would have turned them into museums. Both large and small-scale renovation work was carried out, mostly to preserve the condition of the buildings. However, aside from an absence of clear goals, these projects typically lacked the funds to achieve their aims, at least until the National Palace and Castle Programmes were launched in 2014. This programme, chiefly financed by the EU but also relying on national funding, systematized the cultural and tourist development, uniform management, and utilization of thirty—five (later forty-five—the precise number has fluctuated over time) heritage buildings. The custodian of this castle programme is the legal successor to the Office for the Protection of Cultural Heritage and the Heritage Protection Officer, the Forster Centre. Professional restorers, art historians, archaeologists, and architects approached the work with renewed vigour, but efforts to ‘restructure’ Hungarian heritage protection, or, to put it bluntly, to terminate it, led to the closure of the Forster Centre, and with it the end of this programme, though it was resurrected a few years later, this time under the name National Heritage Protection Development Non-profit Ltd. And perhaps now, having seen the restored main buildings handed over last year (the renovation of outbuildings has not yet commenced anywhere), we can say that the reconstituted castle renovation programme is at last bearing fruit. However, the question of how the edifices will be maintained in the long run, after the initial publicity has faded, still remains unanswered: their functions as museums or event venues will hardly suffice to cover the upkeep of these castles in the long run. But let us not be killjoys, and instead take a closer look at these renovated buildings, and attempt to give a brief, potted history.

The Castle at Tata

The Baroque residence of the comital branch of the Esterházy family, which dates back two and a half centuries, stands amid beautiful parkland above the Old Lake in Tata. Viktor Szentkuti and M Architect Office, which are overseeing the work, evoke the building’s past through a sensitive renovation which respects architectural heritage.

The history of the aristocratic residence dates back to the eighteenth century, when the Tata–Gesztes estate became the property of Count József Esterházy, a seneschal. His successor, the diplomat Ferenc Esterházy, began construction, entrusting Jakab Fellner with the design. What had been the manor-house of an official was expanded into a palace, while a smaller, two-storey residence with two corner towers was built to accommodate aristocratic guests. According to chronicles, the garden contained a sculpted fountain by Antal Schweiger, depicting the nymph Amphitrite and a dolphin projecting a jet of water from its mouth. The statue, which had been supposed lost, was discovered during the landscaping of the castle park, and was re-carved by sculptor Attila Csák on the basis of a surviving photograph from the 1930s.

The castle tells its own story: the rooms have been carefully restored, supplemented, or reconstructed on the basis of old photographs. The Baroque panelled doors, library book cabinets, five hundred square metres of wide-plank parquet hidden under glued linoleum, and bathrooms tiled in Delft or in rustic pink marble, are all once again in place. Many details are known from the series of photographs taken by Oszkár Kallós in 1930, at the behest of the family. Today, in one of the salons where replacing the original furniture and paintings was deemed impossible, a large-scale Kallós photograph on the wall shows how the room once looked. In the ancestors’ gallery, commemorating the counts Esterházy, the lost family portraits have been replaced with new acquisitions, which were miraculously preserved in the gold-decorated, green wooden cladding frames. The first portrait in this gallery is of Count-Palatine Miklós Esterházy (1582–1645) of the Forchtestein branch, and the last is of imperial chamberlain Miklós Esterházy (1775–1856).

Various historical events are linked to this castle. It was in the tower room that on 14 October 1809 Francis II, Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary—who had fled here from the French—signed the peace treaty which Napoleon would later countersign at Schönbrunn. After this defeat, the emperor and his wife, Archduchess Maria Ludovika, were guests in the Esterházy Palace for three months. Ninety years later, between 12 and 15 September 1897, as part of ‘joint imperial manoeuvres’, both King-Emperor Franz Joseph I and Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany were the guests of Count Miklós József Esterházy at his estates in Tata. The twentieth century did not prove uneventful either: after his ill-fated second attempt to regain the throne of Hungary, the last Habsburg monarch, Charles

I of Austria (Charles IV of Hungary) was taken into custody in Tata together with Queen Zita and their companion Count Gyula Andrássy, in October 1921.

The home of the Devil Rider

Hungarian legend remembers Count Móric Sándor as the Ördöglovas, or Devil Rider, about whom numerous equestrian stories circulated in the nineteenth century. He swam his horse across the icy Danube, rode into a ballroom on horseback, and introduced himself to his future wife by simply leaping into the driver’s seat of her carriage in Vienna. And the lady in question was not just anyone, but Leontine, the daughter of the infamous imperial chancellor, Prince Metternich.

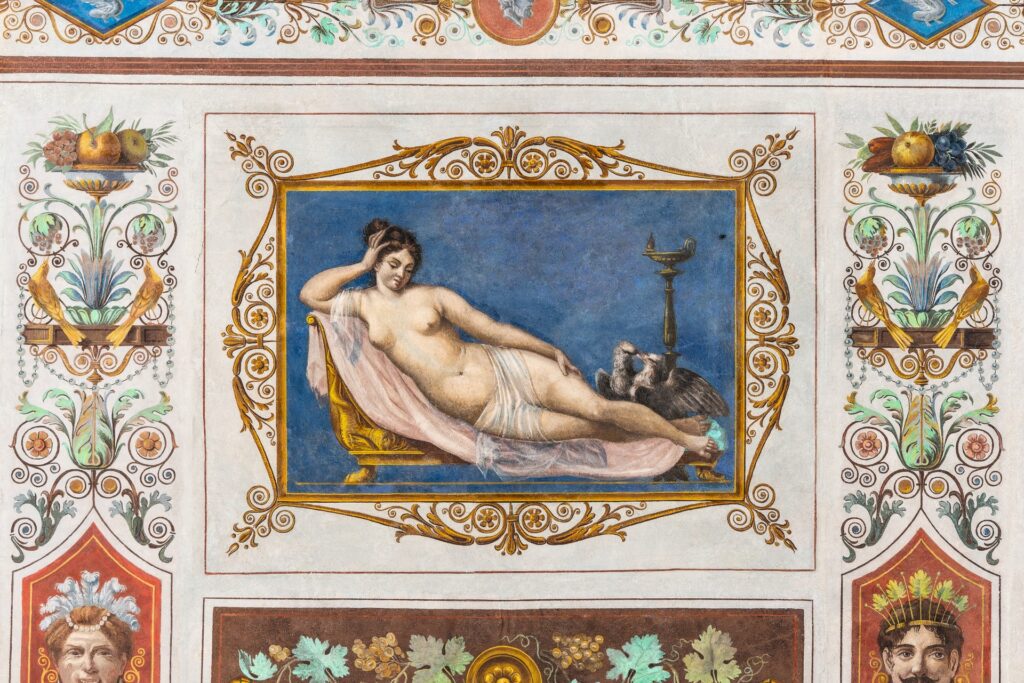

Móric Sándor commissioned József Hild, a famous architect of his time, to rebuild the family castle in Bajna. Hild adapted the Baroque hunting lodge to the classical style, connecting the ground-floor outbuildings to the single-storey main wing with its four-columned portico. Historical records indicate that the count met Alessandro Sanquirico, the set designer for La Scala in Milan, in Italy in 1833, and asked him to decorate the castle. To this day, his art in the so-called ‘Rafael’ and ‘Etruscan’ halls are highly praised. The meticulous, brightly coloured ceiling paintings of the Rafael Hall depict mounted tritons and the Olympian gods. The other room is decorated with Etruscan vase patterns, shaded with yellow and ochre tones. The only surviving sofa of the completely looted castle, also designed by Sanquirico, is in a ragged and decayed state, but remains on display today just as it was discovered, as an eternal memento.

One incredible but true story concerns the rescue from near-terminal destruction of a ceiling fresco in the castle. When the ceiling and roof were replaced in the 1970s to preserve them, this ceiling had to be demolished, and two restorers, Róza Szentesi and János Illés, removed at their own discretion the frescoes from the Raphael Hall and carefully stored them away in pieces in the belief that they could be returned to their original place after the ceiling had been replaced. This was not the case, but they kept the pieces, which were later re-assembled by the painter-restorer Péter Boromisza, the son of Róza Szentesi, when the house was restored.

The planners of the restoration were architect Zoltán Erő and interior designer Klára Szilágyi, who strove for authenticity and a renovation which would show the various construction periods. The exhibitions in the ground floor spaces relate the history of the castle, while the exhibition in the upstairs halls tells the story of the passionate count and his no less remarkable daughter, Paulina, who became the wife of a diplomat and was admired by many writers, composers, and painters.

Tudor-style romance

Nádasdladány, the former home of the counts Nádasdy, is unique among the historical castles of Hungary. This building, then a Baroque manor house, was where the scions of two ancient noble families, Count Ferenc Nádasdy and Countess Ilona Zichy, fell in love. They were married, and in the early 1870s they began the planning and construction of a castle, in conjunction with István Linzbauer, an architect from Kassa (now Košice, Slovakia) who worked in Budapest, and Nándor Hübner, an architect from Székesfehérvár. At their request, the old one-storey mansion was not demolished, but was supplemented with a two-storey main building with a large basement. This is how, in the middle of an English-style parkland rich in exotic plants and made spectacular by a waterfall and an ornamental water tower, the busy, almost whimsical, neo-gothic building complex with a corner tower and crenelated buildings was created.

After the death of Linzbauer, Ferenc Nádasdy entrusted the design of the interiors—the library, the chapel and the ancestors’ gallery—to Alajos Hauszmann, who would later go on to complete the redesign of the Buda Castle. Following the plans of Samu Pecz, the carpenter Endre Thék and two glassworkers named Ede Kratzmann and István Forgó created the wooden masterpieces of the library and the stained-glass windows of the ancestors’ gallery, while the ornamental metalworker Gyula Jungfer, following plans laid down by the most illustrious masters of national historicism, created the ornate, wrought-iron chandeliers.

Although the lady of the house did not live to see the rebuilding of the castle—after five years of marriage, she was taken away by cholera at the age of twenty-four—her husband finished everything just as they had planned it together. Ferenc Nádasdy raised their three children, and mourned his wife for the rest of his life.

The fate of this castle, which was nationalized and allowed to disintegrate like the rest, was borne at a distance by the last member of the family, Count Ferenc Nádasdy, the great-grandson of the builder, who established the Nádasdy Foundation for Art and the Environment in Canada and the United States in 1992. Its principal patrons have included the president of the Hungarian Republic, the governor general of Canada, the governor of New York State, and Otto von Habsburg. It was Ferenc Nádasdy’s wish that the castle should never cease to be the property of the state, but should once again shine with its old light, through its establishment as a lively intellectual centre. In this spirit he founded the ecological academy. According to his original plans, after the renovation the castle would have housed a residential teaching, research, and conference centre.

While this dream has not yet been realized, the main building in the renovated parkland has at least regained its original splendour. The generous interiors—under the supervision of lead renovation designer Lajos Ónodi Szabó—have been revitalized, with many decorative period elements and exhibitions reconstructing family life, curated by historian Balázs Bányai. Full-length portraits which had been preserved, either in walled hiding places or, chiefly, in the Hungarian National Museum, were returned to the ancestors’ gallery. The three paintings absent from the National Museum’s permanent exhibition have been replaced by copies, while those that have disappeared entirely have been replaced by blown-up black-and-white images from contemporary photographs. The two portraits by Gyula Benczúr, depicting the couple who built the castle, are of particularly high artistic value. The library, with its coffered wood ceiling and panelling is stunning, but unfortunately only 1,500 of the former 25,000 books with the Nádasdy seal can be found here.

What has been achieved thus far is worthy of the former owners, but the restoration is not over, and only if the ‘utilitarian’ planners can go beyond the thinking which sees the house simply as an attractive background for weddings and film shoots, will the dream of Count Ferenc Nádasdy be fulfilled.

Life in Füzérradvány

The Károlyi Palace in Füzérradvány was built in a vast, forested park in the north-eastern corner of Hungary, nestled amid the Zemplén hills. The basis of today’s building complex, the presumably L-shaped, two-storey, towered, late Renaissance mansion, dates back to the second half of the sixteenth century, and records suggest that when it became the property of the Károlyi family at the end of the seventeenth century it was already in ruins. The building took its present shape between 1857 and 1859, according to the plans of Miklós Ybl, who also designed the Budapest Opera House, the Castle Garden Bazaar, and many other castles and palaces. The legends of Füzérradvány tell how the owner, Count Ede Károlyi, who had something of a reputation as an amateur architect, was always trying to get involved in the design of this spectacular castle, so that ultimately, the F-shaped structure with its octagonal tower and historicist loggia were completed in 1877 largely in accordance with his ideas, and the plans of János Zitterbarth. However, the construction of the castle did not stop here: Ede Károly’s son László commissioned the Viennese architect Alberto Pio to replace the south wing with a much higher two-storey structure, with a special emphasis on incorporating antique and Baroque elements, including twisting columns, carvings, fireplaces, and artefacts which he and his wife, Countess Franciska Apponyi, had purchased in France and Italy.

The castle entered a new era when, in the 1930s, it passed to László’s son, István Károlyi, and his wife, Princess Maria Magdolna Windischgrätz. Inspired by twentieth-century ideas, and based on the plans of György Lehoczky, they turned the castle into a luxury hotel, introducing electricity, installing suites, constructing villa buildings, and adding sports facilities in the park. Count Károlyi was a keen hunter, and so exotic trophies were also hung in the castle at the time. Those pieces which still remained in the middle of the 2010s were fortunately able to be housed in a museum, at the request of Count László Károlyi, a descendant who now lives in Fót. Statesmen and artists spent time at Füzérradvány in its heyday, and scenes from films shot there preserve the life of the aristocratic castle during the last years of peace.

The designers of the exhibitions in the renovated castle have chosen an experimental approach to presentation. They employ the possibilities of twenty-first-century technology and interactive software to tell the story of the castle and introduce visitors to the secrets of the aristocratic world.

And what is to be done after restoration?

After several decades of vicissitudes, the Castle Programme now appears to be on the right track, and with a number of renovation projects having been successfully completed and handed over last year, the hope is that this year new projects will be embarked upon. But without any wish to spoil the mood, the question of ‘what then?’, what is to be done after the restoration is completed, still looms as the eternal problem of renovated castles. Undoubtedly, restoration is the necessary first step, but it is worth anticipating these questions in advance, because in the long run it is inconceivable that a castle can exist simply as a museum: it is essential for each property to develop a unique programme and function of its own, such as the ecological academy of the Nádasdy Foundation, to plug the structure into the currents of intellectual thought both in Hungary and internationally. This is the real task of the future.

Translated by Thomas Sneddon