Tamás Krump, a Hungarian Christian, Founds a School

in the Most Populous Muslim Country in the World

In 2001, I sojourned at a parish home led by the Jesuit Father István Jaschkó in Taiwan. I strolled through the rooms of the institution, noting the tender care lavished on every aspect of the building. After lunch, I had a long conversation with my host about the beauties and hardships of missionary work in East Asia. The institution Father Jaschkó created, literally from the ground up, is an orphanage and foster home. It took him more than half a century to build up his empire of hope in a place where before there had been nothing but hopelessness.

Father Jaschkó of the Society of Jesus, or Ye Yo Ken as he is locally known, told me about his harrowing vicissitudes in China and then in Taiwan. We had known each other by correspondence. He had read my book on Sándor Kőrösi Csoma, in Hungarian and also in English translation. Now, in the flesh, he struck me as a self-confident but humble man as he spoke about his experiences, and the challenges he had to face during his decades-long missionary endeavour in Taiwan.

How did I end up on the island of Flores?

‘There are Hungarian missionaries working in Indonesia, under far more difficult circumstances than I do’, he remarked instead of complaining about his own hardships. ‘It would be worth your while to meet them one day.’ This put the bug in my ear. A white-haired, towering man with a beard, Jaschkó is advanced in years but mentally fresh, even quick, emanating an aura of sheer love and tolerance for humanity.

A few years on, I held a talk about Indonesia in the Hungarian town of Kalocsa. After I finished my presentation, an old woman named Mrs Lakatos approached me to say that her brother, a certain Ferenc Mészáros, was working on the Island of Flores as a missionary for the Verbite Order (officially the Divine Word Missionaries). ‘He took with him seeds of our famous paprika spice’, she recalled with a smile. ‘He told the people of Flores that ours was the finest chili in the world and advised them to grow it.’ The Kalocsa pepper did make it to remote Flores but, as it turned out, failed to thrive in the tropical climate.

These two encounters and what I had heard about the Hungarian brethren in Flores were followed by a story set in the Raja Ampat archipelago, populated mostly by the Papua people. An Indonesian chef from Flores, who had moved to Sorong, told me that he came from an all-Christian family. His mother was lying sick with a severe case of appendicitis in a small village near Ruteng. Her case was brought to the attention of a Hungarian missionary named Father ‘Mesaros’, who rushed her to hospital where she underwent a last-minute life-saving operation. The Indonesian man felt eternally indebted to the altruistic Hungarian pastor, who not only spread the Word in the jungle but showed his faith in deeds by offering help to someone in great trouble.

These stories strengthened my resolve to travel to Flores and meet my compatriots who lived, worked, and struggled in that remote corner of the world, all the while extending a helping hand to those in need.

I have made several trips to Indonesia, the largest Muslim country in the world with its 276 million inhabitants. While the hegemony of Islam nationwide is beyond a doubt, some of the country’s islands boast far-reaching and strong roots in Christianity. The first European ships to appear on the shores of the Southeast Asian archipelago, in the sixteenth century, sailed under the Portuguese flag. Magellan’s seamen erected the first crucifix in 1521 on the island of Mactan near Cebu in the Philippines. Magellan was killed by the natives, but Christianity more than survived. It is today the largest religion in the Philippines, with over 100 million believers. In Indonesia and Malaysia, the Muslim faith reigns supreme, though for different reasons.

The Island of Flores is one of the major strongholds of Christianity in Indonesia. A long-held dream of mine came true in May 2019 when my plane—it was a Garuda flight—landed in Labuan Bajo. There was no one to greet me, other than the infernal heat. All I knew was that all the Hungarian missionaries were dead, except for one named Tamás Krump, who held out somewhere deep in the jungle not far from Ruteng. I had no address or phone number, yet I was confident I had not come in vain. At the office of the county bishopric the phone kept ringing but no one answered my call.

I got much luckier with the information service at the airport. ‘I am heading to Ruteng to see the Hungarian school and the missionaries. I need to rent a car’, I said to the desk clerk, who introduced himself as Lorenzi. His face lit up in a smile. He told me he knew about a certain ‘Father Thomas’ living in nearby Ketang, who had built a church and a school named St Stephanus in the jungle. Lorenzi had been a boarding student at the school and was ready to help. A few minutes later a driver named Timotheus materialized, wearing a crucifix on a silver chain around his neck and driving a Toyota four-wheel drive. He also knew ‘the old Hungarian father’, who taught him at the same Sanctus Stephanus School and baptized him and his siblings. ‘Father Thomas is a very good man’, he assured me. ‘Everybody loves him.’

Encounters like this are a miracle, I said to myself as the driver negotiated the steep, meandering mountain roads interspersed with landslides and fallen rock. The tidy rice fields gave way first to a coconut palm grove and then to the all-but-impenetrable jungle. It was the tropics all right, south of the Equator. On arrival, I was greeted by the sight of picturesque dwellings scattered around the hillsides, a teahouse with fibreboard walls, and a throng of cheerful children screeching and running about. The heat had subsided to become quite bearable by the time we had reached an altitude of 600 metres.

The sun sets fast at six o’clock here in the Manggarai Regency. It was dusk when, after a drive up a winding valley road, I first set my eyes on the church and the secondary school named after Saint Stephen, along with the other facilities on the grounds, including a dormitory and well-kept sports fields. There were meticulously maintained gardens and a riot of colourful flowers everywhere. This veritable Garden of Eden is called home by Tamás Krump, who first set foot on Flores in 1962, more than half a century ago.

A Hungarian priest in the Indonesian forest

First meetings, those first handshakes, are always unforgettable. Father Thomas had known nothing about me, but it took us less than ten minutes to hit the same wavelength. We felt we had known each other for decades. I handed him a few of my books and a bottle of Unicum I had brought from Hungary as a gift.

With his towering stature, charismatic personality, authoritative presence, and inimitable, impish smile, Father Thomas won me over instantly. He conveyed to me the sad news that his fellow Verbite priest Ferenc Mészáros had died, leaving him the last and only Hungarian missionary on Flores to administer sermons in both Manggarian and Bahasa Indonesia, and to care for his flock.

We talked over strong Indonesian coffee, and later over dinner. Munching on chicken fried rice, eggs, and steamed vegetables, Father Thomas eased into the mood as he spoke slowly and articulately, in impeccable Hungarian. It had been years since he last uttered a word in his native tongue, but he kept himself up to date by listening to Hungarian National Public Radio, the only Hungarian station that has reception in the southern hemisphere.

‘It is my destiny to have lived here in Flores since 1962’, he said. ‘It was God’s will.’ ‘How did you end up so far from Hungary?’, I asked him.

‘I was driven out of the country by the Second World War. In the fall of 1944, we were forced to leave our apartment in Damjanich Street in Budapest, and then the country. It all seemed so hopeless. We had no choice but to flee. We were fearful of the Soviet troops who had flooded the country, looting everywhere and deporting many innocent civilians … Our family decided not to have that happen to us. We had to start a new life, penniless, and without any prospects. My studies were in limbo. Then, as luck would have it, I met a benevolent Austrian missionary named Karl Netta, whose connections landed me in one of the best secondary schools in Austria, the one in Bischofshofen run by the Verbite Order. They gave me quarter and an education. I will remain grateful to them forever. After graduating, I entered the Order and made solemn profession in 1960. I had always been fascinated by missionary work and remote regions of the world. I loved geography, spent a lot of time poring over and perusing maps. I voraciously read travelogues and books on historic expeditions. I visited the missionary museum in Mödling. These experiences and countless conversations led me to work toward a missionary assignment of my own, even as I knew it would take a great deal more study, preparation, and “training of the soul”.’

‘How did you come to Flores of all places?’

‘I was ordained by Bishop Franz Jachym on 18 March 1961. I was soon elated to learn that I would be dispatched to remote Indonesia in the company of fellow priests of the Order. Our ship sailed from Genoa and made a stopover in Naples, where we disembarked to discover the city. As Ferenc Mészáros and I tried to find our ways in the crowded Neapolitan alleys, both of us had our wallets stolen in the tumult. We lost all the money we had, but our passports were saved because we had not kept them in our wallets. So you might say the journey was hardly off to a good start, but I decided it was not so bad after all. At least the mishap made it easier to say farewell to Europe. I have now spent a much greater portion of my life in Indonesia than in Europe, but I have not been robbed once. The journey by sea took weeks, and we felt completely exhausted by the time we reached the port of Jakarta. A few weeks later, we found ourselves in the Manggarai Regency on the Island of Flores, where we had to learn the local language. Rutang was very underdeveloped at the time, without piped water, electricity, or roads. If you wanted to reach a village some way out of the city, you had to walk or ride a horse.’

Father Thomas is a humble man who will never brag about his achievements. If last rites had to be administered to a dying person, or a baby had to be baptized, he had to go to the remotest village even if the land was drenched in torrential monsoon rains because the believers needed him and he was the only one around.

The parish of Tamás Krump and Ferenc Mészáros included more than twenty thousand people. The two priests toured the villages on horseback. It was much later that they switched to motorcycles. These days, Father Thomas drives a Toyota four-wheel drive nicknamed Sanctus Stephanus. On one occasion, he baptized a newborn by candlelight in a storm. Later that day, he had to administer extreme unction in another village. He made it at the very last minute after considerable delays caused by the fierce winds and heavy rain.

Apart from tending to his congregations, Father Thomas has devoted all of his energy to organizing schools. He built several schools and churches with the help of his connections and efficient financial support from his Verbite Order back in Europe. ‘We had to lay every single brick of the church wall ourselves because we had no one else to do it for us’, Father Thomas explained.

The missionary does far more than just see to the spiritual needs of his followers. The community turns to him for help with all kinds of troubles and affairs, from land transactions to plumbing repair, nursing, tooth extraction, health problems, and financial matters. The mission also supplied basic medication to the locals in a humanitarian effort that was not without precedent. Back in the Dutch colonial times, in the 1930s, Hungarian sisters worked as hospital nurses in Larantuka, on the islands of Adonara and Lembata, and even served at leper colonies in Mulawato and Lamalewar. Many of them died of malaria; some fled to Australia before the Japanese invasion.

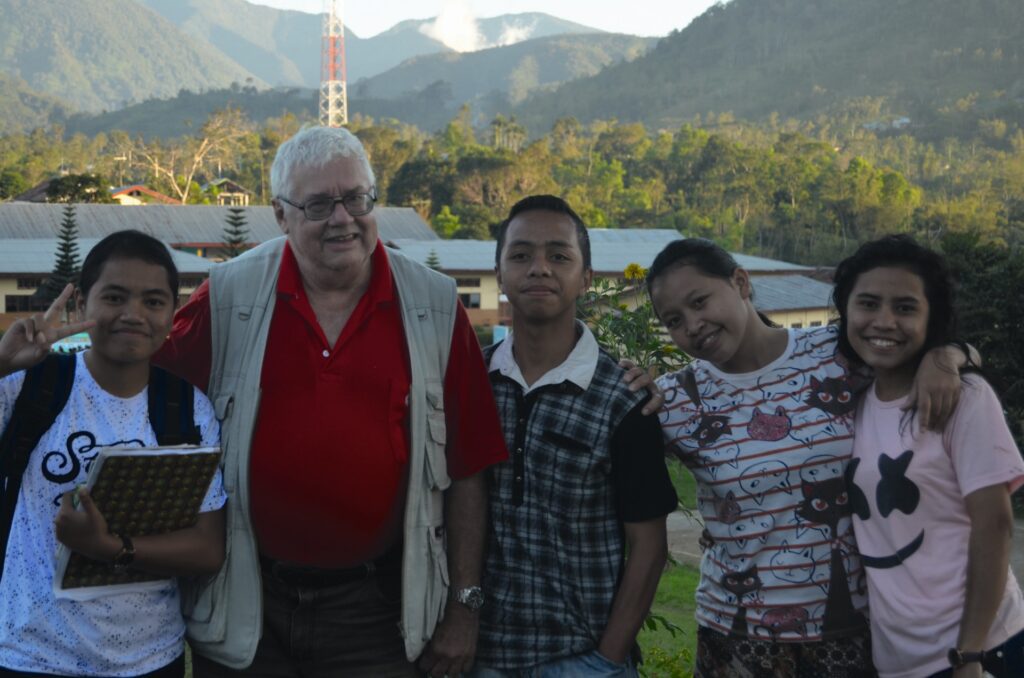

Among the students of Saint Stephen School

The days I spent with the teachers and students of the Saint Stephen Catholic School were an experience I shall never forget. The students, more than 500 in total, wear the name of St Stephanus on their uniform and pride themselves on attending the institution. Each morning they line up in the square in front of the school to raise the national flag while singing, in Bahasa Indonesia, the Saint Stephen march they composed themselves, and the Indonesian national anthem.

A painting by the main school building pays tribute to the Hungarian king who founded the Hungarian state. It is the work of an Indonesian artist, based on a picture postcard portrait given to him by Father Thomas. I had the opportunity to sit in on various classes, library seminars, and discussions. Curious to find out more, I asked the students what they knew about Saint Stephen.

‘He was a Hungarian king. He was Christian.’ ‘He was a good man. He founded a country.’ ‘He was brave and he defended his people from the enemy.’ ‘He lived where Father Thomas was born.’ ‘Father Thomas loves Saint Stephen very much, and we love Father Thomas very much, too!’ The answers differ slightly, but all the students are proud of their patron saint. The name of St Stephanus is present everywhere, on jerseys, in classrooms, and on the school’s crest.

As a testimony to the high teaching standards and the enthusiasm of the educators, many children are fluent in English at the age of fourteen or fifteen, although the official language of teaching remains Bahasa Indonesia. The schoolmaster asked me to hold a presentation illustrated by slides about Hungary and Hungarian explorers and researchers of Indonesia. More than five hundred chairs had to be brought into the gym for the occasion, as everyone was eager to hear what this distant visitor had to say. My presentation was rewarded by thunderous applause, and the children formed a long line in front of me. I had to shake hands with every one of them, one by one. They placed my hand on their foreheads as a sign of their respect. I had never been granted such honour before. The ceremony of shaking hands with five hundred children lasted well over an hour.

The school in the jungle offers children from needy families the opportunity to study and rise in the world—something that no other institution around here can provide. Those unable to pay the monthly fee for boarding send a bag of rice. In the village of Ruang, I witnessed twenty-one children take their first communion in the presence of their parents and extensive families.

Having built several schools and churches, Father Thomas still often takes to the road of trust and love to reach his flock in barely accessible villages. More than a priest, he is someone to whom the humble farmers can and do turn for advice regarding property issues, financial problems, and even family feuds.

Father Thomas rises at six each morning and sounds the bronze bell of his church. He celebrates mass in the Bahasa Indonesia language in the Paroki Santa Perawan Maria Yang Diangkat Ke Surga, that is, the Parish Church of the Assumption of Virgin Mary. Beside the traditional psalms, the church resounds with a song lauding Saint Stephen, sung ardently by a choir of one hundred to one hundred and fifty children. In Flores, where 90 per cent of inhabitants profess the Catholic faith, the long-term viability of Christianity is signalled by the fact that more than two hundred Verbite novices studying at the Saint Paul Major Seminary at Ledalero have chosen to serve God as their lifelong calling.

It is a miracle to hear Ketang, this tiny village in the tropical forest less than a thousand kilometres south of the Equator, reverberate with the peal of a bronze church bell brought here halfway across the globe by the Hungarian Verbite missionary, who has sounded it every 20 August, on Saint Stephen’s Day, for more than half a century.

Translated by Péter Balikó Lengyel