János Pánczél Hegedűs in interview with Gergely Szilvay

Currently, the main problem of the right is that it is paralysed and it feels it has to meet the expectations of the left, says János Pánczél Hegedűs, after Thomas Molnár, the Hungarian- born American philosopher who passed away in 2010, and about whom he has recently published a monograph. Our interview addresses the questions who Thomas Molnár was, what his opinion was on the right wing and on conservatism, and what he would say about contemporary populism.

GSZ: How did Thomas Molnár see the world?

JPH: He was a Hungarian-born right-wing Catholic philosopher living in America, still regarded as a conservative by many, even though he rejected the adjective. At home, his works became known after the 1990s, finding a favourable reception among Hungarian readers in the new intellectual milieu following the political transition. The professor must have been delighted, as he had proudly referred to himself as a Hungarian all his life. The first major conference on his oeuvre was organized in Hungary in 2009, shortly before his death, after it was derailed the previous year by the Philosophical Committee of Department II of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, claiming that Tamás Molnár was, in their opinion, ‘far-right’. However, the conference hosted by Sapientia Monastic College was opened by the chairman of the Academy. In one of his best-known books, Liberal Hegemony, Molnár discusses liberalism as one of the engines of modernism. He fought against modernism all his life. For Molnár, the political right and religion are closely intertwined: the right relies on religion, protects it, draws from it, and is inseparable from religious life; what is more, right-wing politics is a kind of practical application of religion.

GSZ: What did Molnár consider a functioning social order?

JPH: I think his concept of authority is crucial. He defines authority in opposition to the leftist concept of an oppressive authority: authority for him is social cohesion which transforms and integrates at the same time, and is as natural as love. It is natural because there are differences between people; there is no equality, we were created like this, and this is what is right also from the perspective of natural law. Our task is to do our jobs well and to live our lives the right way, but at the same

time we are dependent on one another, which creates differences in society. These differences inevitably generate authority in the system of interrelations between people.

If authority is removed, something else will fill the ensuing vacuum, a distorted authority, if we are lucky, or, if we are unlucky, an abstract form of power, such as, for instance, totalitarianism, which theoretically proclaims brute equality of and for the people, but through the imposition of a simplified, ruthless hierarchy. According to Molnár, there have always been historical elements that drive and enrich modernism: popular sovereignty, the spread of the herdenmensch (the average person, one of the multitude), the turning away from the transcendent and the sacred, and the abuse/misuse thereof.

GSZ: Molnár is vilified by the left as ‘far-right’, in spite of the fact that he was sent to Dachau. What could be the reason for this?

JPH: Molnár was sent to Buchenwald and Dachau because he participated in the Belgian Catholic resistance and as a foreign student he was suspicious anyway. Molnár’s approach to the right is significantly more nuanced than that of his liberal, democratic, or leftist critics. In Europe, he was primarily in contact with French and Spanish right-wing groups, mostly with Carlists, Falangists, French monarchists, and right-wing nationalists, and, indeed, he sympathized with Franco. All this had an impact on how he was categorized, which is therefore unfairly one- sided and distorted. For Molnár, this is what the political right is. After all, he was and integralist traditionalist Catholic after the Second Vatican Council. He bought a holiday home in Spain in the last years of the Franco regime, probably with the help of his influential supporter, Alfredo Sánchez Bella, and for a long time it was there that he spent his vacations and met people who were important to him. For him, the right in Europe was represented by Carlism, Francoism, and the vivid intellectual medium of French nationalism and monarchism, which were characterized by personalities rather than political parties. In all of this, Molnár never took part without being critical, and he was also open in other directions, not only within the right—see the neopaganist French new right—but outside it as well.

GSZ: Molnár who frequently criticized liberalism and democracy, found refuge in the home of liberal democracy, the United States. Isn’t there a contradiction in this?

JPH: There was a period when he defended the United States. In his book The Counter-Revolution, for instance, he claims that European civilization has two pillars left: the Catholic Church and the United States. Several decades later, in his book about Atlantic culture, he turns this into criticism, as he thinks that these pillars are faltering; he considers the Second Vatican Council as the Great October Revolution of the Church, and the United States, in his view, has with the passage of time been pervaded by the spirit and practice of liberalism, which has had a negative impact on Europe too. In the West, mass democracy has become the dominant force, and also a kind of religion; people’s thinking has become too mechanical, and the United States has become the spearhead of globalism, spreading the vulgarized experience of the herdenmensch most effectively. The United States, he believes, has Americanized Europe, but Europe has been unable to properly exert its influence on America, and what used to be European there has been essentially lost, or is unable to assert itself any longer.

What Molnár liked about the United States was that the Europe which had existed before the revolutions could be transplanted and preserved there, in certain forms and with a certain content, especially in the South. He retained this conviction— which has remained popular among conservatives to this day—for an extensive period of time. But from the end of the 1970s it all changes, and Molnár gradually becomes disillusioned with the United States. The creation of the EU was always strongly criticized by Molnár, who called it the Disneyland of Europe, and in his view, it meant the end of European-ness as such, which will only benefit the United States.

GSZ: Was Molnár ungrateful to the United States?

JPH: He mentioned in several texts how grateful he was to the United States for taking him in and providing an existence for him. But he was unable not to express his criticism of what he was unable to be grateful for. As he pointed out, the gratitude of the heart does not exclude objective analysis. It was no accident that he waited three decades before formulating his critique of America in two books (L’Americanologie; The Emerging Atlantic Culture), and during the Cold War he was pro-America as he saw the United States as the main force capable of defeating communism, and until that at last happened, he was willing to put aside other considerations. He expected that once communism collapsed, nation states would become stronger. But instead, it is consumer society, consumerism, globalism, and the liberal hegemony that have become stronger.

GSZ: It is a widely held assumption that Thomas Molnár worked for the CIA. Do you know anything about that?

JPH: I think this is because he travelled extensively. He lectured in South America as well as South Africa, and returned regularly to Spain. This is why some people have presumed that perhaps he was a CIA agent, whatever that means, but I have not found any source to confirm this; it is probably just an urban legend. His biography still needs a lot of research.

GSZ: What would Molnár—who was not a fan of democracy and popular sovereignty— think of so-called ‘populism’ in our time?

JPH: First, he would certainly provide a detailed account of where the term comes from and what it initially meant. Then he would perhaps add that after 1945 the right became a mirror image of the left, and thus adopted tools and notions which the left was keen on using, such as popular sovereignty. Molnár did not consider the principle of popular sovereignty satisfactory. For him, the big question is, if the people are sovereign, who are the subjects? Populism, originally, is a neutral political term, but in terms of its reception and the scope of its application, it is rather part of the left’s arsenal, and it follows left-wing patterns of thought.

GSZ: Are subjects necessary?

JPH: There are subjects, always, but we do not always use this term to refer to them. There is always a political elite actually ruling, exercising power. And those who are below them are the subjects, even if they are not referred to as such.

GSZ: Can we compare Molnár’s aversion to popular sovereignty with the way today’s liberal–leftist technocratic elites feel aversion to the people? After all, the political right today calls itself pro-people in opposition to this.

JPH: I would say this is just a coincidence, and the two things are different in reality. Neoliberal technocratic elites have a visceral aversion to the people. Molnár, however, was against popular sovereignty as a point of principle, and, needless to say, technocrats hold diametrically opposing beliefs concerning the world. Molnár, by the way, claimed that mass democracy meant the loss of original sovereignty and authority. In his view, it is an unnecessary compromise to refer to the representation of certain people instead of referring to rule as such. In Molnár’s interpretation, mass democracy and the rule of parties cause the death of the genuine right wing. After 1945—a year he considers a historical turning point from the perspective of the right—the authentic right-wing person for him is a hero fighting against negation which has turned into a global system—that is, modernism. Adopting any tool of the left is a compromise, unnecessary in the long term. Those on the right who adopted certain tools from the left failed tragically. The consequences should be seen clearly. After 1945, right-wing politics is non- existent for a long time; it is mostly in art and culture that the right wing can evolve. This paralysis of the right, which is advantageous for the left, should not continue—the right needs to make its own culture and art, and needs to pursue its own politics.

Molnár observed that the right is always showing a forgiving attitude to the left, but this is a one-sided affair, as the left has thus always managed to preserve its political seeds in periods of right-wing dominance, which would spring up again in more favourable circumstances. Molnár uses a remarkable simile: in his view, right-wingers have been living in constant fear since 1945, dreading the moment when a left-winger would issue a warning that you are not a democrat, that you are a fascist, or anything else that horrifies the public. But, asks Molnár, why should anyone care about this? His answer is that he is not a democrat, and does not want to meet the expectations of the left. He is an independent right-winger. In his opinion, the right should simply try to exercise authority instead of giving consideration to whether it is a bad thing in the eyes of the left or the democrats. These things follow from one another. As a Catholic, he was against abortion, for instance. In his view, if we say yes to abortion, then we should not be surprised that the father’s authority or the parents’ authority in the family crumbles, and sexual libertinism spreads. And, before his time, he raised the question: if abortion is allowed, will we also allow changing one’s gender? So, if we accept an unnecessary compromise once, then we will be faced with new ones, one after the other, and, at the end of the process, the essence of our political creed will be lost.

GSZ: It is interesting that even though Molnár was a combative right-winger who would not be called a ‘whiner’ today—he argued that Louis XVI’s unwillingness to order the troops to open fire was the original sin of the right, that is, surrendering in mental combat. He did not really see any room for action in the political arena.

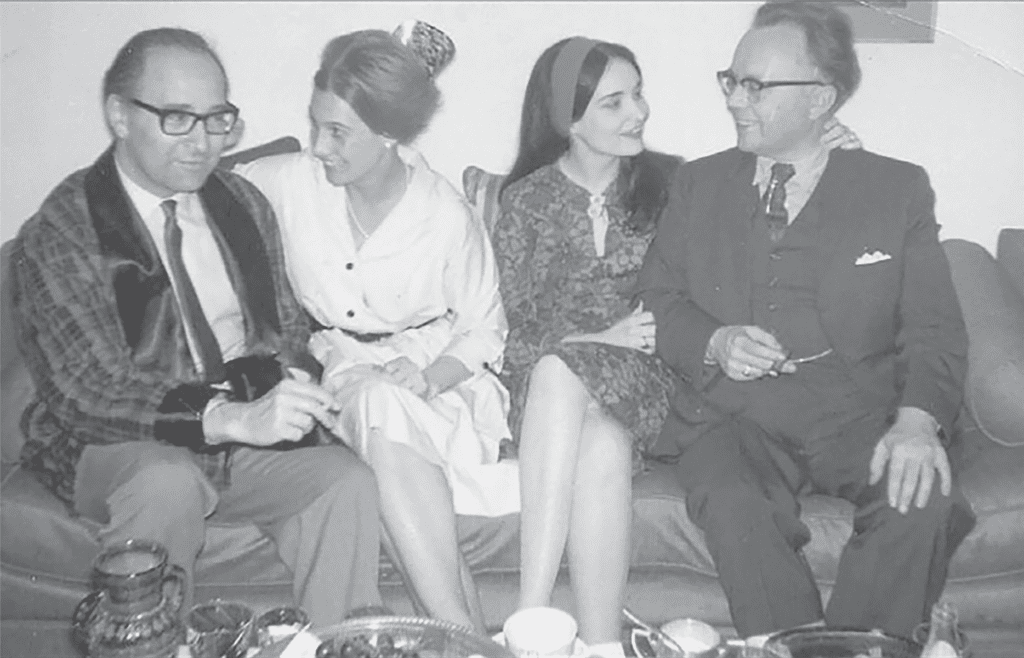

JPH: Molnár only appears to be combative compared with those who you call ‘whiners’. He was, in fact, a highly sophisticated man of society, a real gentleman. His first wife was a ballet dancer, and with his second wife—another Hungarian emigrant—they had a circle of people where he enjoyed exchanging ideas, and not only with right-wingers. He wrote one of his most famous books in collaboration with the neopaganist new-right Alain de Benoist, polemicizing with him.

Molnár always craved a vibrant cultural and academic life, both in the United States and in Europe. He once defined what a perfect right-wing cultural experience was for him: to watch a film of one of the former students of Mircea Eliade about the French royal palace, to attend traditional Latin mass, and to go to a play in a French theatre in the evening. This is not a combative attitude. He wrote all his books from his heart, not from an urge to justify himself as a philosopher. He was always ready for discourse, believing he should not use any arguments he was unable to defend. He accepted Elemér Hankiss’s invitation to Hungarian television, accepted an invitation to a leftist forum of debate, and also appeared on Pannon Rádió. He had his own column in Havi Magyar Fórum (Monthly Hungarian Forum), and published articles in the journal Jel (Sign). He had an open intellect: he did not know me when I went up to him after one of his seminars, but we talked for an hour. I was a twenty-something nobody, but he honoured me by paying attention to me anyway.

GSZ: Did he enjoy life?

JPH: He certainly did. He was very into smoking, for example. He told me once that he was infuriated at an airport when he was asked to put out his cigarette. I think he was a chain smoker. If cultural pleasures are part of the enjoyment of life, then he certainly enjoyed life. He went to the theatre regularly, travelled, and sought the forums of social life. I would not say he was a hidebound man of letters, tied to his desk. His appearance, however, made him a typical conservative professor for me, even though he did not consider himself to be one. I will never forget how he walked in the streets of Budapest in perfectly ironed white shirts, cane in hand, and with a jacket thrown over one shoulder, even in the summer.

GSZ: For the right in the twenty-first century, how relevant is the suit-and-tie Thomas Molnár criticizing popular sovereignty and democracy?

JPH: In 2019, I wrote my book A rend bástyái. Molnár Tamás politikai filozófiájának alapelvei (The Bastions of Order. Thomas Molnár’s Principles of Political Philosophy) about him partly because the internationally recognized Thomas Molnár had hardly any impact on and in politics. In the 1990s, in the predominantly liberal climate of opinion, he was simply too much for the realpolitik of the age. At the same time, two thirds of his works were published in Hungarian, including the most important ones. It has always appeared rather strange to me that it is impossible to trace any direct impact of his on politics, thus I also tried to outline the practicability of policies based on Molnár’s approach. One good question is, does a political community exist that would be able to identify with this?

I think all philosophers who refer to everlasting things and ideas continue to be relevant. According to Molnár, the political communities which shape humankind only offer us the immanent, while the left and modernism have cut us off from the transcendent. I believe Molnár’s ideas are easy and beneficial to translate into practical considerations. He himself practised this: he regularly wrote articles on current affairs, triggering the indignation of the intellectual community every time.

Molnár’s concerns included the eternal values as well as the current issues of the right, the theory of authority and the practical applications thereof, modernism, the challenge posed by the left and liberalism, the right-wing segments of culture, the counter-revolution as the activity and existence of the right, and so on. A politician may avoid these issues, but in that case he or she is a right-winger only according to the current political setup, which merely means not being a leftist, or being someone the left does not consider one of their own.

GSZ: In today’s intellectual life, the first thing we think of when we hear ‘critique of modernism’ is postmodernism. Is there any connection between Molnár’s critique of modernism and postmodernism’s critique of modernism? Or is this merely a coincidence of terms?

JPH: This is just a superficial coincidence of terms. According to Molnár, postmodernism had a chance to transcend modernism, but instead merely radicalized it. Molnár believes the most beneficial outcome would have been if postmodernism, by transcending modernism, had brought back pre-modern interpretations and practical possibilities. But instead, modernism reached a new stage, with technocracy and the mechanization of human thinking attempting to usurp the role of the soul. Postmodernism, however, for those of us who live in it more and more, is more favourable in that it has pushed the boundaries a little further, and so now it is not mandatory for us to accept all the interpretations of classical modernism at face value, we can deviate from them, although by doing so we perhaps sink even deeper into postmodernism.

GSZ: You have mentioned that Molnár did not consider himself a conservative. It has always been a popular thing among thinkers regarded as conservative to emphatically declare, referring to minor differences, that they are not conservative: think of John Lukács, for instance. However, based on the most commonly applied criteria, many, including Molnár, can be called conservative. What was his problem with the adjective?

JPH: I think we often say ‘conservative’ when we want to say someone does not belong to the left and we want to put it mildly, trying to say something that is more acceptable. According to Molnár, every conservative sooner or later becomes a defender of the status quo, but he did not want to preserve the status quo of modernism. Besides, in his view, conservatism is a mask in the modern era, with classical or modern liberalism hiding behind it.

GSZ: This may only be said of the Anglo-Saxon world.

JPH: Yes, but he was more familiar with Anglo-Saxon conservative circles, while he was a Francophile all his life, with a preference for continental counter- revolutionaries and right-wingers. At home he was also categorized by many as an Anglo-Saxon conservative, a charge against which he protested vehemently. And there is an additional difference between his thought and conservatism. In his view, conservatism is contemplation, but the right wing is action, and he preferred action. I would say he was a right-wing philosopher who also identified with the conservative position. He had the ability to adopt the conservative position in a pamphlet, in discourse—for instance, he examined fascism from a conservative angle in one of his writings—but politically he was a right-winger, essentially, a European Catholic right-winger, in the original sense of the term.

GSZ: In The Counter-Revolution he writes that those on the right have been afraid of taking action ever since Louis XVI, due to some hang-up, to some inhibition. How might it be possible to do away with this hang-up?

JPH: I can see you really like this reference. It is often asked about our own Blessed King Charles IV how he failed to issue an order to open fire in 1918 when he wanted to do it—but he did not have any soldiers left to carry out his orders. He did want to give such an order when the revolution broke out in Budapest, and the commanding officer of the city was also on his side initially. In my opinion, this really is a paralysis of the right. But we are discussing this in 2019, with several paralyses of the right behind us. When Molnár stated here in Hungary in the 1990s that he subscribed to the right, it needed extensive explanation in any circle of people. The paralysis of the right is manifested in that it has tried to defeat the left and modernism several times, but always with tragic results. There was the classical elitist attempt in the nineteenth century, then at the beginning of the twentieth century the right tried to adopt the tools of the left and relied on the masses, with mostly Faustian personalities at the helm who spoke and led the way in their own names but wanted to do something for the nation. After 1945, according to Molnár, there were only two roads to take: in the East, the gulag, the gallows, and internment; and in the West, consumerism and conformism, which devoured the right.

We have been over this same ground many times. Today, there is a stronger urge in you to comply when you say you are a right-winger than in 1990.

GSZ: I would dispute that. It is the other way round.

JPH: I do think the urge is stronger. Isn’t populism an urge to comply?

GSZ: According to its own narrative, populism today equals taking people’s problems seriously as opposed to looking down on them, and stripping off the earlier right-wing elite’s compulsion to comply.

JPH: But populism includes saying yes to mass democracy. Isn’t it also an urge to comply? In the thirties, no moderate conservative—such as Count István Bethlen—accepted democracy, and they did not have to provide an explanation for it. They were in a position to speak their minds to anyone. Democracy today is a religion or a substitute for religion, something to be aligned with, something to comply with first and foremost.

GSZ: But you cannot say publicly that you are not a democrat if you want to take action in the given political situation. And why shouldn’t anyone be free to identify himself with right-wing values, saying he would like to promote them in a democratic climate? This is the framework for action today, and if you do not accept it, all you can do is shout from the side of the field in vain, no matter how right-wing your principles are.

JPH: That is probably right, you cannot reject democracy even if you are on the right. But let’s make this clear: this is a symptom of the paralysis we referred to. You should add, without saying it aloud, that you simply refrain from doing it because you are in power or you want to exercise your power and govern, and democracy is a tool for all this.

GSZ: To what extent were the necessary compromises of realpolitik, which the right used to emphasize the contrast with intellectuals’ navel-gazing, respected by Molnár?

JPH: Well, he regarded those right-wing politicians of the twentieth century as valuable personalities who did not make compromises, or made only a few, and also managed to avoid falling into the modern trap of totalitarianism: Franco, Pinochet, de Gaulle, although the last one made several compromises. As for Hungarians, he appreciated Miklós Horthy, Béla Imrédy, and Otto von Habsburg, and he also mentioned József Antall after the political transition. They are very different personalities, but what he appreciated in all of them was that they carried out a kind of restoration, attempting to create an organic social order.

It was quite fitting that in the middle of the 1960s he became the editor of Triumph, a journal supporting Carlism and traditionalism, in addition to Anglo- Saxon conservative organs in the United States. By the way, he also broke with them after a while, as he had broken with almost all other communities, because his personality was too strong.

GSZ: You mean he was not a team player?

JPH: He was not, or he was, but only for a short time. He was able to align himself with and fertilize a community with his ideas, but after a while he distanced himself from almost all of them. There were no more than two or three people who enjoyed his permanent friendship over several decades, but he kept in touch with a lot of people. He did have an extensive social network.

GSZ: Was he a doctrinaire, to some extent?

JPH: Molnár was not a doctrinaire—he was independent. As regards ideas and concepts, he refused to make compromises just to maintain good relations with anyone.

GSZ: What did his religiosity, which determined his work so strongly, entail? I am asking only because in Moi, Symmaque he wrote that if he had lived at the time of the emergence of Christianity, perhaps he would have been a pagan, in order to preserve and conserve the old faith.

JPH: It is one of his most personal works, with arresting symbolism. His deep religiousness was due to the influence and strong faith of an Irish-born American nun, Helen Casey, who confronted him by saying that the lukewarm, formal religiosity of his childhood was not sufficient, and he should start to live his faith. This was a protracted process for him. His long first marriage was not a holy matrimony, but his second marriage was. Thus, from the 1970s, for him, religious practice and existence merged. From then on, he was persistent. He had been an adult for a long time when his faith crystallized in him, and many people say he lived a bohemian life beforehand. Subsequently, however, his faith led to an apologetic religiosity, and he also defended the institution of the church. He wrote several important volumes on the philosophy of religion. He constantly defended Catholic doctrines, and believed that everything he claimed could be deduced from his Catholicism, so he was not very forgiving towards Protestant denominations or other religions. I do not share his perception of Catholic mysticism, for instance, as he strongly criticized Meister Eckhardt, a Christian mystic of the early Middle Ages. Molnár claims mysticism makes us believe that man can become god-like or part of the divine, which goes against the belief that God exists and the world created by Him exists, independently from man’s consciousness, and man tries to grasp it with his consciousness. So I think Molnár is a moderate realist Christian, who can be rather associated with neo-Thomism. In my opinion, however, there are so many positive things in Christian mysticism that purely by its existence it offers an alternative to modernism which negates and neglects the transcendent.

GSZ: Is it not possible that Molnár also overvalued reason and rationality, and that his approach to faith was too rational?

JPH: Certainly not. It is important to understand a thinker’s influence, the fruits of his efforts. According to Molnár, Christian mysticism may result in an intellectual heresy, which in turn can in many cases lead to self-deification. He tried to seize problems by their roots. This is why he is so unforgiving towards Kant, Locke, and Hegel. In his view, Locke’s concept of private property was already one of the pillars of modernism. So the impact of philosophy on society cannot be neglected. The left had established its philosophical foundations before they were put into action, which demonstrates how abstract the left is. The right, on the other hand, stands for everything against which the left was established, and therefore the entire pre-modern society and worldview can be regarded as inherently right-wing.

The political right managed to work out its philosophy only by the time the left had established its own hegemony. Thus, the right is always a step behind the left. The right maintains that there are existing, created things, and those things have their own properties. The left maintains there are processes and conditions, which change constantly. According to Molnár, the right and the left have always existed, as both approaches have existed and will always exist. Once this dichotomy ceases, it will only benefit the left, because then equalization and levelling will come, which will replace natural inequality with distorted inequalities. What those who today say there is no longer any right or left really mean is that only the left exists or only the left is necessary. Since Creation, there have been differences between men. Denying differences means the denying of Creation. Therefore, if there is a right and a left, Molnár prefers to choose the right.

Translated by Balázs Sümegi