An International Comparative Analysis

INTRODUCTION

This paper aims, first of all, to introduce various tax structures, as well as the criteria which may be applied by countries to the implementation of their specific tax systems. Subsequently, we will outline the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on the tax system in general, before highlighting the most relevant specific tax measures. Finally, we shall provide a summary of how the tax policies of individual countries evolved in response to the COVID crisis, and how the priorities of tax structures were altered by these measures.

1. THE CONCEPT AND CONSTITUENT ELEMENTS OF TAX STRUCTURE

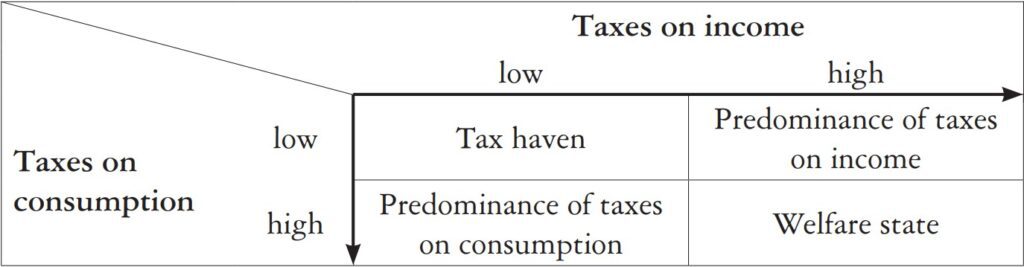

By ‘tax structure’ we mean the totality of tax types applied in a given country; that is, the tax systems of individual countries can be structured in accordance with the types of income and assets to which taxation is applied, the types of tax applied by the state, the rates of taxation, and with actual cases and extent of exemptions, if applicable. State taxes can be divided into two main categories: taxes on income and taxes on consumption. (It should be noted that certain countries also use taxes on property, charging taxes on possessing or using movable or immovable assets. However, in view of the fact that in many countries property tax either does not exist or plays an insignificant role, it will be excluded from the scope of our discussion.)

Taxes on income and taxes on consumption are linked in everyday practice, since income tax is applied to part of the generated income, while the remainder can be then used for consumption or savings. Income used for consumption or savings is subsequently also burdened with taxes on consumption (for example, value added tax, or VAT). The income–turnover interrelation can be understood as follows: all taxes on income limit opportunities for consumption, and consequently indirectly limit the opportunities for taxes on consumption. This interrelation is also demonstrable the other way round: taxes on consumption limit disposable income (income which can be used for consumption and savings).

Windfall taxes should also be mentioned. These are introduced provisionally by states to balance the budget: such taxes typically hit sectors which have benefitted from an extraordinary situation or crisis. Accordingly, the purpose of windfall taxes is to allow the state to redress the imbalance between winners and losers of a crisis by assuming a stronger role in the economy. That is, windfall taxes allow resources to be reallocated from organizations enjoying higher income and profits during a crisis to social groups which have suffered disproportionately from its effects.

1.1. Taxes on Income

A tax on income is a tax charged on the income produced either by a private individual or by an organization. Personal income tax and corporate income tax, for example, belong to this category.

To this day, the public perception of income tax is that it is the fairest of all taxation types, since it ensures a differentiated allocation of tax burdens. For example, in the case of personal income tax, the tax administration can also take personal circumstances into consideration, such as the number of children in the household. As a result, in many cases, it is also possible to achieve secondary economic policy goals through the way taxes on income are charged. Such secondary policy goals may include, in the case of personal income tax:

- increasing the consumption and savings of households;

- facilitating the repayment of household debt, and

- supporting the decision to have children.

In the case of corporate income tax:

- incentivizing entrepreneurship (investment);

- stimulating economic growth, and

- promoting employment.

1.2. Taxes on Consumption

A tax on consumption is a tax charged in relation to the consumption or purchase of certain products or services. Examples include VAT, excise tax, and customs duty.

At the same time, a major problem in the case of taxes on consumption is that the entity bearing the tax burden and the taxpayer are decoupled, thus the entity bearing the tax burden has no interest in following up the payment of the tax in relation to the specific product or service, while the organization obliged to pay the tax has a financial interest in concealing its revenue. Accordingly, the tax-gap indicator will show a difference between tax payable after actual transactions in the market and consumption taxes actually paid. It should be noted in advance that based on data issued by the European Commission, this indicator was 10.9 per cent in Hungary in 2020, as opposed to 21.6 per cent in 2009, which means that 89.1 per cent of the sum total of VAT on actual business transactions in the Hungarian economy appears in the Hungarian budget. In this, Hungary is ahead of its neighbours, including Slovakia (21.2 per cent), Poland (14.6 per cent), and the Czech Republic (15.3 per cent), and some of its major business partners, including Germany (12.1 per cent) and Austria (11.5 per cent).11 European Commission, ‘Study and Reports on the VAT Gap in the EU-28 Member States’, 2020

Final Report. European Commission Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union, Brussels,2020

Transaction taxes are perceived by many as socially insensitive, since the tax must be paid in each case, and the extent of the payment is unaffected by the identity of the entity obliged to execute it. Thus, the amount of consumption tax payable after purchasing a book, for instance, is identical in the case of a family with four children or a multinational company.

2. THE TAX STRUCTURE AND ITS VARIETIES T

axation is a basic requirement of any state, since the revenue side of its annual budget intended for the maintenance of public finances rests upon it.22 Please note that tax revenues would not be required if the revenues the state generated from its

legal relationships under private law were so high as to facilitate the financing of the state as well

as public services. Currently, the United Arab Emirates is such a state, where no tax revenues are

needed in addition to the funds generated from the sales of oil (qualified as a national asset). At the same time, it is within a state’s competence to determine the types and rates of taxation it introduces. Based on these decisions, countries fall into different categories, as presented below

2.1. Tax Haven

A country qualifies as a tax haven if:

- it does not introduce taxes on income or consumption, or introduces only very low rates of taxation,33 In general, a tax rate of or below 10 per cent is indicative of a tax haven. and

- if the country concerned does not provide information on the revenues and transactions included in the records of banks and authorities.

The OECD44 The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; French: Organisation de

Coopération et de Développement Économiques, OCDE) is an intergovernmental economic organization

with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and world trade. was the first to point out that in the field of tax law, information exchange between tax authorities is of key importance. In the last few years, a large number of agreements on information exchange have been concluded, which is of particular interest as such agreements are usually signed by countries which have no interest in concluding agreements on the prevention of double taxation. In the wake of the global financial crisis which began in 2007, countries with strong economies have put strong pressure on states with low tax rates—which typically also host offshore financial centres—in order to ensure that information exchange agreements should be concluded. The main point of such agreements is that the parties undertake to hand over information considered to be tax secrets to one another in accordance with the provisions of the agreement, for the purposes stipulated therein, within the relevant procedural framework.

Such countries include, for example, the Bahamas, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Macao, Mauritius, Panama, the Seychelles, and Samoa.55 6437/22 Conseil de l’Union européenne, ‘Conclusions du Conseil relatives à la liste révisée de

l’UE des pays et territoires non coopératifs à des fins fiscales’, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/

media/54471/council-conclusions-24-february-2022.pdf.

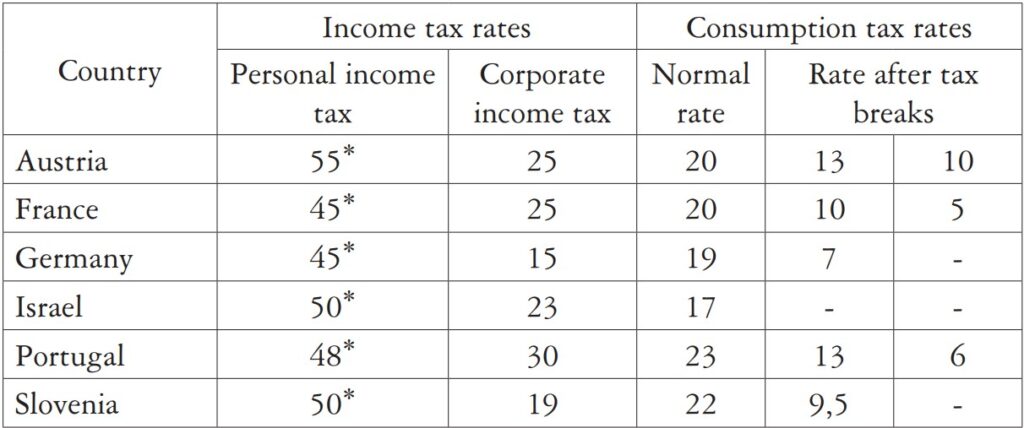

2.2. Predominance of Taxes on Income

A predominance of taxes on income means that the central element of taxation in the country concerned is that a high rate of tax is charged on the income (revenues) of private individuals and organizations there. In such cases, the respective tax rate is 25 per cent or higher. In these countries, economic development can be regarded as constant, where both private individuals and organizations typically have high annual incomes. At the same time, in these countries, private individuals habitually reside, and organizations have registered seats, operating parent companies, or holding companies, and employ various aggressive tax planning techniques that steer the income away from the country where it is actually produced. In the terminology of international tax law, such private individuals and organizations are called beneficial owners .

Countries with a predominance of taxes on income and the tax rates they apply

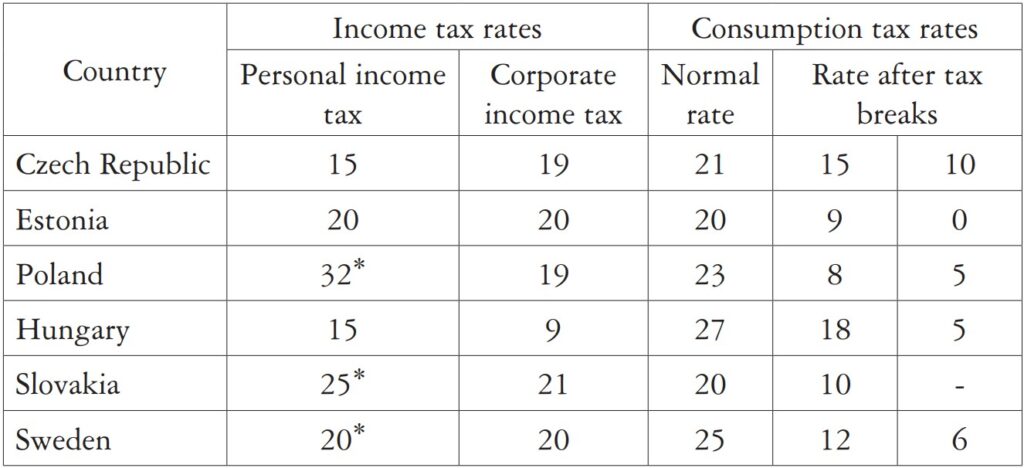

2.3. Predominance of Taxes on Consumption

The predominance of taxes on consumption means that the country concerned applies high tax rates to economic events (transactions) that take place on its territory. Importantly, this method of taxation does not slow down the development of the economy, but at the same time, economic actors participating in consumption have no interest in paying these taxes to the state.

Countries characterized by a predominance of taxes on consumption have taken major steps towards the digitalization of taxation, which has had two main effects:

- first, tax revenues appeared on the revenue side of the budget simultaneously with economic growth, in spite of the high tax rate;

- second, tax evasion became risky and difficult to pull off, and therefore expensive, which contributed to improving taxpayers’ compliance.

If there is a predominance of taxes on consumption in a given country, it also means that taxes on income are low, which makes it possible for private individuals (the population) as well as organizations to increase their savings.

Countries with a predominance of taxes on consumption and the tax rates they apply

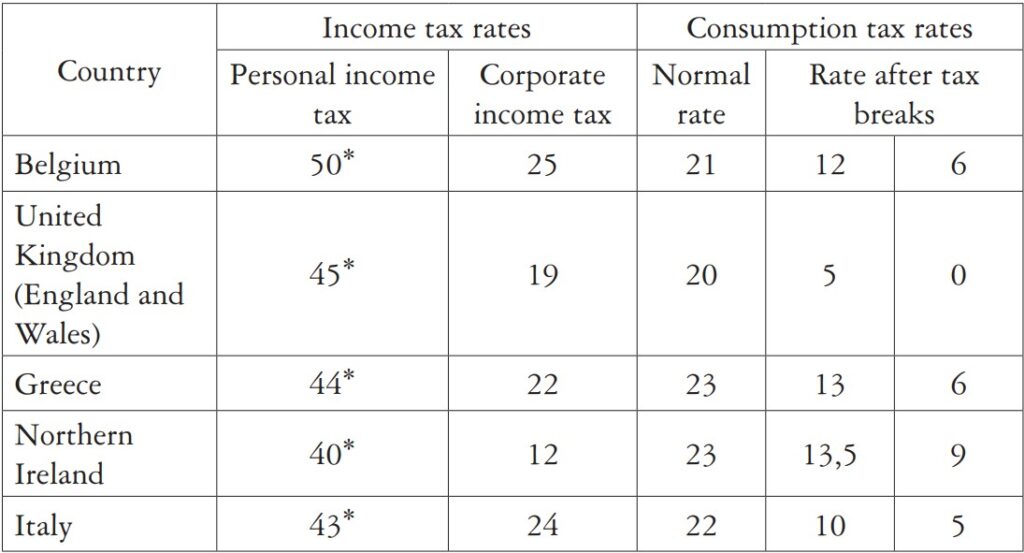

2.4. Welfare State

The welfare state is a system in which the state—based on the ideals of equal opportunity, a fair distribution of wealth and income, and social responsibility for supporting persons who are otherwise unable to provide for their basic needs— protects and supports the financial and social prosperity of its citizens. At the same time, with regard to taxation this implies that such countries are characterized by a predominance of taxes on income while also keeping consumption taxes at a high level, since this is the only way for the state to be able to finance healthcare and education in addition to maintaining the social safety net and offering direct financial aid and benefits.

In a welfare state, the expectation is that the number of its citizens below the poverty line should decrease significantly as a result of taxation and government spending.

Countries operating in line with the welfare state model and the tax rates they apply

3. THE IMPACT OF THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC IN THE FIELD OF TAXATION

Since the start of the pandemic, government response measures have been unprecedented. Decisive and timely tax measures have played a key role in saving jobs and incomes, and in ensuring the survival of companies, with an almost exclusive focus on providing emergency support. Tax measures in response to COVID-19 were aimed at mitigating cash flow challenges faced by companies in order to avoid staff layoffs, temporary insolvency of suppliers, a reluctance to lend money or, in the worst case, the bankruptcy and permanent closure of businesses. In addition, direct support for households was also a set target of the relevant tax measures.66 OECD, Tax Policy Reforms 2021, Special Edition on tax policy during the COVID-19 pandemic

(Paris: 2021).

3.1. Taxes on Income

3.1.1. Measures Affecting Corporate Income Tax

Prior to the coronavirus crisis, the number of occasions on which a country had lowered the rate of corporate income tax was very small, but in order to mitigate the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, this previously rare occurrence became common worldwide. Lowering corporate income tax became the standard practice of many countries. Croatia, for example, lowered the corporate income tax rate for taxpayers who earned annual revenues of at least 7.5 million Croatian kuna from 12 per cent to 10 per cent as of 2021. India decreased the corporate income tax charged on domestic companies from 30 per cent to 22 per cent, and in the case of newly established domestic manufacturing companies, to 15 per cent. Indonesia lowered the normal corporate income tax rate from 25 per cent to 22 per cent, and will further decrease it to 20 per cent as of 2022.

Some countries introduced targeted corporate income tax breaks and tax base reduction measures exclusively for small enterprises. France increased the revenue threshold for small- and medium-sized enterprises to EUR 7.63 million, and introduced a reduced rate of corporate income tax (15 per cent). Hungary lowered the corporate income tax rate for small enterprises from 12 per cent to 11 per cent and increased the threshold of eligibility until December 2020.

In order to incentivize growth, a number of countries implemented corporate income tax reductions for specific sectors or specific types of enterprises. Russia, for example, decreased the tax rate applicable to qualified IT and technology companies from 20 per cent to 3 per cent as of January 2021. Turkey introduced a five-year reduction in the rate of corporate income tax, from 22 per cent to 20 per cent from January 2021, for companies making an initial public offering of at least 20 per cent of their shares on the Istanbul Stock Exchange for the first time. Argentina lowered the corporate income tax charged on companies in knowledge based economic sectors from 25 per cent to 15 per cent. Hungary made efforts to offer a permanently favourable environment for corporate investment. This was the purpose of the full abolition of restrictions imposed on the amount of development reserves. Thanks to this measure, corporate profits may even become fully tax-exempt, if the companies in question commit themselves to implementing additional new investments within four years using the respective amounts. Investment is also incentivized by a significant reduction in the value threshold of the development tax break of small- and medium-sized enterprises: small enterprises may already realize the tax break in the case of investments of over HUF 50 million, and medium-sized enterprises can do so in the case of investment projects worth more than HUF 100 million.

3.1.2. Measures Affecting Personal Income Tax

Some countries introduced measures targeting taxpayers strongly hit by the pandemic. These included increased income tax breaks for households with children (for example, in Germany and Estonia) and vulnerable persons (for example, in Sweden and Germany), and income tax allowance for low-income households. Germany, for instance, permanently increased the annual income tax benefit for single parents from EUR 1,908 to EUR 4,008, and the basic allowance after children was increased from EUR 7,812 to EUR 8,388. Estonia introduced a supplementary basic allowance after the birth of a third child. Belgium increased the maximum amount of childcare costs which can be claimed as a tax rebate. The United States provisionally increased, for 2021, the tax rebate limit for low- and medium-income taxpayers to USD 3,600 for babies and young children, and to USD 3,000 for older children.

Some countries offered tax breaks to the elderly (for example Sweden, Canada, Honduras, and Thailand). Sweden, for instance, increased the general allowance for seniors. Ontario (Canada) introduced the Seniors’ Home Safety Tax Credit, which is worth 25 per cent of up to 10,000 Canadian dollars in eligible expenses in the case of persons with permanent residence in Ontario.

Countries such as Lithuania, the Netherlands, and the United States introduced targeted tax allowances for students and tutors, both to support employment and to develop new skills. Several countries provided targeted tax allowances in proportion to the costs of home office (for example Canada, Germany, New Zealand, and Sweden).

In Hungary, the crisis was especially burdensome for families with children and for young people. The Hungarian government therefore refunded the amount of personal income tax paid for 2021 up to the amount of the average wage as a one-off measure. All parents who are eligible to claim standard family allowance after their children are eligible to claim this repayment, which means that both parents in a family can make use of this opportunity. Tax advances were repaid even before the submission date of personal income tax returns, in February 2022. Besides, for the purpose of supporting young people’s start in life and to increase employment, those under the age of 25 are exempted from the obligation to pay personal income tax up to the amount of the average wage, as of 2022.

3.1.3. Measures Affecting Sectoral Taxes

Several countries introduced reductions of various sectoral taxes. France, for example, permanently reduced production tax for the companies in the industrial sector. As part of the long-term plan of bank tax announced in 2015, the United Kingdom decreased the bank tax to 0.1 per cent, charged on own equity and liabilities of banks over GBP 20 billion as of 2021. The bank levy was also affected: going forward, it is not applicable to overseas activities of banking groups with a registered seat in the UK. Slovakia abolished the bank tax in 2020. In order to support the transport sector, the Czech Republic decreased the road tax payable for lorries by 25 per cent. Poland postponed the entry into force of the tax on retail turnover.

Indonesia exempted revenue derived from dividends from taxation, if the beneficiary was a taxable domestic corporation or individual who reinvested such revenues in the country within a specific period of time (there are minimal investment requirements in the case of dividends received from foreign private corporations).

The commitment of the Hungarian government to long-term sustainability of the budget is also demonstrated by its efforts to mitigate the budgetary impact of the targeted measures right from the beginning, by increasing other revenues. Such additional revenues for the central budget were to be received from sectors that were less affected by the economic downturn. Accordingly, the special tax on financial institutions was provisionally doubled as of 2020, and the special tax on retail undertakings was also re-introduced as a new tax on turnover after the positive decision of the European Court of Justice on the matter.

3.2. Measures Affecting Taxes on Consumption

A few countries provisionally lowered their general VAT rates. In Germany and Ireland, the rate of VAT was lowered for six months, from 19 per cent to 16 per cent until the end of 2020, and from 23 per cent to 21 per cent until the end of February 2021. In Poland, on the other hand, the planned lowering of the VAT rate from 23 per cent to 22 per cent was postponed, because of concerns that it would adversely affect the national budget.

More than half of countries temporarily introduced zero (or reduced) VAT on supplying medical equipment and products (for example, gloves, masks, hand sanitizers). In several countries, zero VAT was introduced in the case of healthcare employees deployed in medical institutions, and measures were taken to ensure the deduction of VAT charged in advance after items donated to healthcare institutions by companies, and/or in order to prevent donations that would trigger the obligation to pay VAT (Belgium, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Thailand).

Hungary also tried to help sectors in trouble by reducing public dues on particularly indispensable products. Since a significant number of restaurants tried to adjust to the new circumstances by increasing home delivery volumes, the VAT on home deliveries was reduced to 5 per cent, a rate similar to that on food consumed on the spot, from the second wave until the end of the lockdowns. Although its impact was felt primarily in the reopening phase, it already offered some help to companies in tourism and the hospitality industry. In addition, Hungary also placed special emphasis on maintaining investment levels, extending a 5-per cent VAT rate on the home construction industry until the end of 2022.

4. EXPECTED DEVELOPMENTS IN THE SYSTEM OF TAX STRUCTURES

Despite a few common trends, significant variations can be seen between regions and countries in terms of tax measures introduced, when, and for how long, since the coronavirus pandemic and related restrictions impacted each country differently and at different times. For example, a number of countries of the Asia–Pacific region which were at the epicentre of the pandemic at the end of February and the beginning of March 2020 managed to control the virus earlier, and subsequently introduced more tax incentives than other countries which were or are still struggling with a high number of infections. The impact of tax packages reflected the fiscal room for manoeuvre of each country, and also the extent to which they were able to lean on the central bank, as many developing and emerging economies had more constricted manoeuvring room regarding fiscal support to be extended to households and business undertakings than did more wealthy countries. The scope and types of tax allowances depended on the architecture of the tax systems of the countries concerned, as well as on the size of their informal sectors and the administrative capacities of their governments.

As lockdowns and other restrictive measures were beginning to be lifted after the first wave of the pandemic, countries started to introduce tax measures aimed at supporting their recovery, including corporate income tax breaks on investment and reduced VAT rates in sectors that had been severely hit by the crisis.

The other major tendency in that period was that an increasing number of countries introduced or announced new tax hikes. While some of these were one-off or provisional measures, most are intended for the long term. A number represent a continuation of pre-crisis tendencies, for example the increase of the excise tax on fuels and CO2 emissions, which have been the most frequently announced tax hikes. The common feature of these rate increases is that they are intended to promote sustainability and the green turn.

Although countries should avoid any premature revocation of allowances and exemptions introduced to combat the COVID crisis, new tax measures must aim to primarily benefit companies and households which were heavily hit by the crisis. Providing support to heavily affected households is indispensable for mitigating the unequal impacts of the crisis and the risk of increased poverty. Similarly, relief should continue to be available for companies operating in heavily affected sectors of the economy

With the economic restart, recovery incentives—through effectively planned tax measures—may have a key role, if consumption and investment levels remain low permanently once restrictions are lifted.77 Györgyi Nyikos and Attila Béres, ‘Entrepreneurial Resilience in Times of COVID-19 Crisis—

Evidence from Hungary’, in Zsolt Becsey Jr, Erzsébet Czakó, Klára Katona, Gábor Kutasi, László

Radácsi, Balázs Szepesi, László Szerb, Enikő Virágh, eds, I. Vállalkozáskutatási Konferencia: Vállalatok

helyzete és a jövő kihívásai – a járványhelyzetre adható válaszok (1st Conference on Entrepreneurship

Research: The Position of Companies and the Challenges of the Future—Possible Responses to the

Pandemic) (Budapest: Iparfejleszté si Kö zhasznú Nonprofit Kft., 2020), 31, 40, 1. In order to ensure the effectiveness of the measures and/or their execution, special attention is warranted in areas where a lack of state involvement may cause significant damage to the economy.

SUMMARY

In the aftermath of the crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic, countries will have the opportunity to perform a fundamental reassessment of their tax structures as well as the role of tax measures introduced during the crisis. In this respect, three aspects should be mentioned, which will have a central role in the transformation of tax structures:

- the necessity of the green turn;

- strengthening the role of digitalization, and

- increasing the weight of consumption taxes.88 Based on Governor of the National Bank of Hungary György Matolcsy’s fundamental ideas, which were expounded in relation to the subject of a new tax reform on 26 April 2022.

The essence of the green turn is that the environmental protection angle should appear in the tax structure; that is, each type of tax must be analysed in terms of how the criteria of sustainability and environmental protection can be built into the system of tax rates, tax allowances, and tax exemptions. The relevant tax measures should be introduced on every occasion in a way that ensures that the benefits can only be claimed by taxpayers who act in a way that protects the environment, and that this should give them a competitive advantage against others who fail to act in an environmentally friendly manner (implementing an investment project that pollutes the environment, for example).

Strengthening the role of digitalization means, first of all, that each tax should be analysed based on which types of tax incentives could be introduced to inspire an increasing number of organizations to adopt digital solutions. As a consequence, a set of criteria must be worked out to make it more worthwhile to finance the digital transformation of the organization than to maintain its existing, conventional operation. Secondly, tax procedures should be assessed on the basis that each procedure should be conducted electronically, primarily, and it should only shift to a conventional, paper-based procedure, or personal administration at the taxpayer’s specific request.

The task in relation to increasing the predominance of consumption taxes means that instead of revenues and profits, only tax rates linked to economic processes should be increased. Since consumption taxes do not hinder productivity, they likewise do not curb economic development. And, importantly, undoing the damages caused by the pandemic can only be accomplished via economic development.

As a side note, it should be briefly mentioned that the introduction and/or increase of sector-specific (sectoral) taxes, the broadening of the tax base, and the expansion of the circle of taxable persons and entities also represent potential solutions. In such a case, however, careful consideration is required when determining which sector should be burdened with a windfall tax, since hitting an erroneously selected sector with a crisis tax may also have undesired spill-over effects.

Translated by Balázs Sümegi

- 11 European Commission, ‘Study and Reports on the VAT Gap in the EU-28 Member States’, 2020

Final Report. European Commission Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union, Brussels,2020 - 22 Please note that tax revenues would not be required if the revenues the state generated from its

legal relationships under private law were so high as to facilitate the financing of the state as well

as public services. Currently, the United Arab Emirates is such a state, where no tax revenues are

needed in addition to the funds generated from the sales of oil (qualified as a national asset). - 33 In general, a tax rate of or below 10 per cent is indicative of a tax haven.

- 44 The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; French: Organisation de

Coopération et de Développement Économiques, OCDE) is an intergovernmental economic organization

with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and world trade. - 55 6437/22 Conseil de l’Union européenne, ‘Conclusions du Conseil relatives à la liste révisée de

l’UE des pays et territoires non coopératifs à des fins fiscales’, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/

media/54471/council-conclusions-24-february-2022.pdf. - 66 OECD, Tax Policy Reforms 2021, Special Edition on tax policy during the COVID-19 pandemic

(Paris: 2021). - 77 Györgyi Nyikos and Attila Béres, ‘Entrepreneurial Resilience in Times of COVID-19 Crisis—

Evidence from Hungary’, in Zsolt Becsey Jr, Erzsébet Czakó, Klára Katona, Gábor Kutasi, László

Radácsi, Balázs Szepesi, László Szerb, Enikő Virágh, eds, I. Vállalkozáskutatási Konferencia: Vállalatok

helyzete és a jövő kihívásai – a járványhelyzetre adható válaszok (1st Conference on Entrepreneurship

Research: The Position of Companies and the Challenges of the Future—Possible Responses to the

Pandemic) (Budapest: Iparfejleszté si Kö zhasznú Nonprofit Kft., 2020), 31, 40, 1. - 88 Based on Governor of the National Bank of Hungary György Matolcsy’s fundamental ideas, which were expounded in relation to the subject of a new tax reform on 26 April 2022.