Film Snapshots of the Man Who Redefined the Tokaj Wine Region

István Szepsy is a member of the sixteenth generation of a winegrowing dynasty in Tokaj, which first left an indelible mark on Hungary’s cultural and economic history in the early seventeenth century. Although I have been following Szepsy’s work only for the last twenty years or so, the first time I met him, it became instantly clear to me that this wine region near the northeastern border of Hungary was displaying incipient signs of blossoming once again, after the destructive decades of communism, and that this soft-spoken vintner from Mád was the most influential protagonist of its renaissance. Ever since that first meeting, I have made a conscious effort— perhaps in part obeying destiny—to make his evolving thinking about the tangible but invisible world available to the public, in the form of a series of in-depth interviews made over the years. Over time, however, I came to feel a need for this unique personality, who had touched many and points far beyond the narrower field of viticulture and enology, to reach an even broader audience, and this called for a new genre.

We first came up with the idea of doing something for the screen, and in 2016 we completed shooting and editing a fifty-minute documentary entitled Stocks of Love: A Portrait of István Szepsy. The film premiered on Duna Television in 2017 and has been aired on several occasions since then. The power and intensity of our protagonist’s entire being are condensed in his inimitably wonderful wines, on which the final verdict will be delivered by our descendants fifty, one hundred, or one hundred and fifty years down the line, given the immense longevity that his Aszús are destined to enjoy. Although he and I have not yet discussed the judgement of posterity, I have no doubt in my mind that his Aszú wines captured in the bottle now will vindicate the enormous effort and sacrifice he has made in the past few decades. Will there be someone to carry on with the Tokaj tradition István Szepsy inherited and is passing down to his children, having enriched that tradition with radical innovations of his own? Someone to tailor this invaluable tradition, glued to Hungary’s national identity, to meet the economic challenges of the twenty-first century, while exploring more deeply every day the privileged uniqueness of this created environment?

Stocks of Love was filmed by the cinematographer Gábor Tóth. I attempted to organize Szepsy’s portrait around verbatim text portions marked by name tags, while striving to provide a comprehensive picture of the winemaker’s still unfolding oeuvre. I hope that the film and its transcript here succeed in drawing public attention to the struggles, innovations, and achievements of this creative mind who turns seventy this year, and whose work is one of great significance for Hungarian agriculture and the image of our nation.

* * *

István Szepsy: Tokaj has always been part of Hungarian history. Of course, we have many good wine-producing regions, which are abundant throughout the Carpathian Basin. Few people know that before the phylloxera plague [at the end of the nineteenth century] Hungary’s wine production was on a par with that of France. So the fate of Hungarian wine somehow mirrors the fate of the nation. I mean the way the quality of consumption plummeted under the communist regime, the way standards shrank in all walks of life. Then the Iron Curtain came down, and a very poor country got down to the work of reconstructing a very costly winemaking process.

The Aszú process goes back almost five hundred years. It was first recorded by Máté Lackó Szepsy, one of István’s lateral ancestors. Now a few words about what Aszú really is. The

definitive grape varieties of Tokaj are furmint, hárslevelű (‘linden leaf’), and muskotály (muscat lunel). Influenced by the River Bodrog the region’s climate creates ideal conditions for the appearance of noble rot (botrytis cinerea) in the vineyards during the harvest season. This is a type of fungus which causes the grapes to shrivel, concentrating the aromatic substance inside. During the process, the sugar content of the grapes rises to extreme levels and distinctive flavours develop. The aszú berries, individually hand-picked to this day, are macerated in base wine. Following lengthy maturation in casks and in the bottle, the naturally sweet Aszú wine is born. The principal variety supplying both the base wine and the aszú berries is furmint. The uncommonly labour-intensive Aszú—the crown jewel on the table of European monarchs throughout history and a vital source of income for financing the Hungarian War of Independence led by Prince Ferenc Rákóczi II at the turn of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—was almost entirely destroyed by the ubiquitous, tastelessness, inferior quality wine mass-produced during the decades of communist rule. It was a ravaging of resources which not only wreaked havoc in the vineyards and cellars of Tokaj, but also trampled human lives and souls under foot. The effects of this desolation are still being felt today.

István Szepsy: Value hierarchies were toppled and transformed, and the prices of produce and agricultural products fell to unprecedented lows, especially in comparison with the cost of energy. In the 1950s, we had no utility bills. Today, the annual rate of new births is less than one tenth of what it was in the fifties.

The generation or generations who were genetically bound to the land are now gone. They were the ones who could not imagine their lives without the scent of the earth, without their attachment to it, without husbanding farm animals or growing grapes. The new generation that came along could no longer produce sufficient income from the land in an economy without specialized markets, so they were deprived of the chance to cherish cultivating it. The greatest damage was done, of course, by the squandering of stock in several senses of the word, as after the war, the region lost the stocks of landed aristocratic domaines to nationalization, then the stocks of the peasantry to forced collectivization, then the stocks of state-run coops—along with other national assets—and finally the stock of trust vested by citizens in the system.

Szepsy was quite young when he lost his father, a widely respected figure in the wine region. Having completed his university studies, he fled to Paris, where the thought of leaving Hungary for good first occurred to him. However, on his third night there, he saw nothing but Tokaj in his dreams. He returned home and accepted the position of chief horticulturist at the Rákóczi Specialized Cooperative. He had to wait a decade and a half before he was able to take advantage of the opportunities afforded by the change of regime in 1990 by embarking on building an estate of his own. He quickly found himself in a radically new situation, in which he—along with the wine region and the entire country—had to face a number of hitherto unknown challenges.

István Szepsy: Many, many years ago this process started where I had to rely on others to find solutions to certain problems, and I saw that it was not going to work. We are talking about a year or two after the fall of communism, and I said to myself, there is no other way, I must take care of those things myself, things I had expected others to do for me. I mean I had to begin to appreciate our potential on a higher level, with the requisite respect and gratitude, and to work to standards that would reflect my own state of awareness at the time, rather than obeying some economic calculations. So I had to overturn a fundamental premise. I had to come out and say that we were engaged in a business enterprise, but that this enterprise was not founded on economic considerations.

Dr Gabriella Mészáros (international wine academic): We held this landmark tasting at the Yellow Wine House, which was attended by István, among others. We sampled a huge number of Aszús. We were working through item 26 or 27, I think, when an Aszú came up that was something totally different. The line-up had included many interesting and wonderful wines, but this one was a game- changer. It was the early nineties. Think wines completely different in style from what you get nowadays. When that one hit the glass, I said, hold on, something is happening here.

When the new democracy set in, it dawned on Szepsy that he had to learn the workings of global wine markets, and also relearn his own trade. He was among the first in the country to realize that the quality and value of the wine at bottling hinged on the inherent quality of the grapes as grown in the vineyard. He started limiting his yields more drastically than anyone else. During the first years, the radical steps he took in the vineyard made him the object of ridicule in Tokaj. In truth, what he set his sights on at this time was not simply the quality renewal of Tokaj in grape-growing and winemaking, but the highest possible pinnacles of quality, which he has been actively pursuing ever since—ultimately, the loftiest standards to which Tokaj is destined and compelled by its historical greatness.

István Szepsy: It is about whether you want to build a top global brand or you don’t. Our natural assets tell us that we should, no question about it. We must answer the call to demonstrate this rare innate quality of creation that is magnificent, amazing, and capable of altering the consciousness, the minds of people. For a long time, I went about my professional tasks by obeying the intuitions I had. Much of what we have been doing since 1992 is not taught in professional training, or if it is, it is taught in completely different ways. Yet here I was, telling myself to listen to my hunches.

His Aszús may have elicited admiration around the world, from London to Hong Kong, but Szepsy had to confront the relentless laws of a global market and find answers to the

daily economic problems which often threatened even the survival of the undertaking. He had to take up the challenge in part to remain able to run his family winery and in part to preserve and pass on to his children a lifestyle and a grand Tokaj tradition that was fast disappearing. At the turn of the century, vinophiles had just got tired of chardonnay and begun to idolize everything else, from sauvignon blanc to malbec, offered by run-of- the-mill wines sourced from a world which had succumbed to globalization. The Old World had simply become boring, and who wanted to dip into wine from a drab corner of Europe everyone looked down on? It was around this time that Szepsy bottled his first release of dry furmint, after the grape’s adaptability had drawn his attention to the geological diversity under his feet and across the entire wine region. It was also then that the furmint variety became the focus of his endeavours.

István Szepsy: Fifteen years ago I didn’t know that I needed a part of the Szent Tamás [Saint Thomas Vineyard], let alone what kind of different parcels that vineyard might have. I didn’t even know the Úrágya.

In the right circumstances, the Szent Tamás can reveal secrets that truly make all your senses shiver. It is capable of astonishing depth due to this very special zeolite rock formation I found here, in fact three of four different types of zeolite stratified over the bedrock. The cracks and fissures of that bedrock serve as conduits for various weathered debris, some of it calcareous, which is transported to the surface. This probably has to do with the fact that this

vineyard was originally used as a sacral or ceremonial space, as the name of Szent Tamás suggests.

Hedvig Tallián: How did you discover the Úrágya vineyard?

István Szepsy: By happenstance, just the way we hit upon the Szent Tamás. Except that nothing is accidental, as you know. What happened was that someone came along who opened my eyes to it.

When dry wines moved onto my radar screen, that was actually when the vineyards began to reveal themselves to me. My vision shifted onto a different plane. I was living under the barrage of new impressions, dizzy with the astonishing wealth of new possibilities. To think what treasures had been squandered or relegated to obscurity here! Each of these plots has a different rock composition underneath, though even the one farthest out is less than two hundred metres away.

I think that the Szent Tamás probably yields the most complex wine, precisely because of those many layers of zeolite, although the Úrágya is even more characterful, because that’s the vineyard we have the most experience with. It is manly and mineral, and is among the first to become ready to drink. The Urbán needs more time. It is our most long-lived dry wine.

These vineyards and parcels have immense character, and of course the wines they make have the potential to represent the wine region and the country in a way that can lead us toward an entirely new level of knowledge, advocacy, and recognition. More generally, they can guide us to a new, deeper understanding of the treasures lying at our feet.

After implementing a series of bold measures, Szepsy managed not simply to restore the honour of the Aszú but to reform it. By redefining the potential of the wine region, he made it possible to start expressing the unique character of each location through single-vineyard dry furmint releases. His commitment to and sense of solidarity with the wine region and its broader communities drove him to help found and participate in local civil organizations of the trade. For example, the Mád Circle Society of Protected Origin undertook to set forth product specifications to define and protect the authenticity of origin, quality, and distinctive individual character of the wines. True enough, tightening regulations on the local level before 2010 was also necessitated by detractors among the officials of the national government at the time. The specifications adopted by the Society formulated expectations that were much higher than those prescribed by law. They regulated the parameters of wines labelled with a village designation, a step above the regional appellation. The most stringent of all is the category of single-vineyard wines, which can only be labelled as such if they faithfully express the character, acidity spectrum, and unique mineral composition of the given vineyard—in short, a distinct personality. But giving expression to such individual character comes at the price of strictly limited yields. Fifteen million years ago, the Tokaj foothills underwent an intense

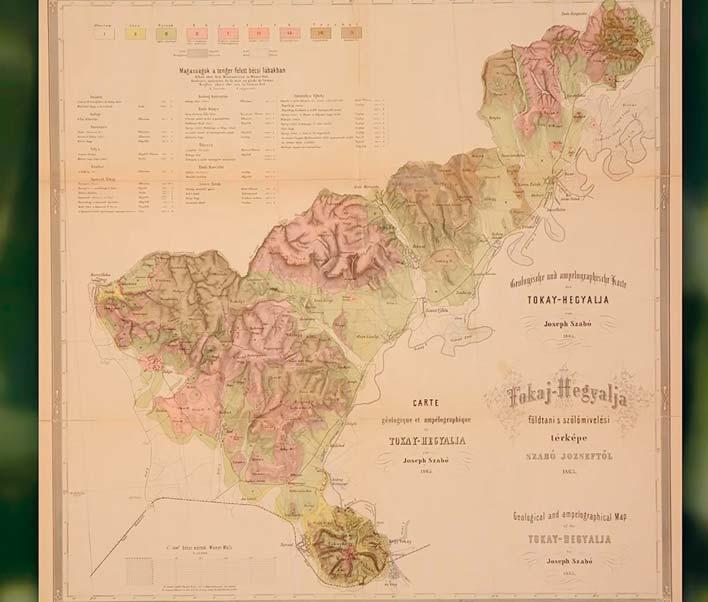

hydrothermal process in the depths of the Pannonian Sea, owing to the activity of typically smaller, puffing volcanoes under the water surface. This created the varied and stratified mineral formations without which these rare wines could never have been born in what became the wine region as we know it today, long after the Pannonian Sea had receded.

It was this geological diversity to which the furmint grape so finely adapted, with its own distinct clones and strains. Recognizing this, Szepsy set about the work of mass selection, followed by a narrower focus on clone and bunch selection. His painstaking documentation of the adaptivity of furmint serves the ultimate goal of attaining exalted wine quality.

The seemingly novel but in reality long dormant considerations he embraces have so far fallen on the wayside in the life of the wine region, if not been entirely obliterated from memory. People simply lost sight of them, and they remained hidden in the maze of historical and political upheavals, such as Hungary’s territorial losses in the wake of the Treaty of Trianon [Versailles, 4 June 1920] or the communist disdain for quality. To make things worse, the local scientific institutions failed to stand up for the growers’ interests. All of this now seems to be changing.

Szepsy continued to refine his definition of top quality based on his ever-new discoveries, which in turn intensified his desire to express the unique character of each of his vineyard holdings in Tokaj.

The entry of dry Tokaj furmint on the global stage of wine astonished even the most influential critics. In one of the spring 2010 issues of the Financial Times, Master of Wine Jancis Robinson published an article entitled ‘Hungary for Progress’, hailing the dry whites of Szepsy and other reliable growers in Tokaj as viable alternatives to fine Burgundy, the most precious white wines in the world. Even though this appraisal and other occasional accolades like Robinson’s failed to bring about the big public breakthrough, fine-dining sommeliers in Europe and across the Atlantic began to discover Hungarian wine, and notably the dry furmint of Tokaj. These days, more and more Hungarian wineries enter various international competitions, albeit Szepsy himself has been cautious enough to stay away from events that tend to pigeonhole wines and subordinate judgement to commercial considerations.

István Szepsy has garnered all wine trade awards there are to be won in Hungary, including Grower of the Year in 2001, Winemaker of Winemakers, and the Prestige Award, twice. His contribution has been recognized by two high-level state decorations, and recently he received the Lifetime Achievement Award of Hungary’s Wine Academy. He has been elected member and chair of various civil wine organizations. A few years ago, he retired from these community obligations to concentrate all of his considerable energy on his terroirs.

Ákos Forczek (Hungarian wine merchant in London): It was Szepsy’s wines that taught sommeliers during the past fifteen years what Tokaj was all about. We were the first to invite serious, Michelin-starred sommeliers to visit István in Tokaj. They all fell head over heels in love with what he was doing. He is now recognized as the ambassador of Hungarian wine not just in London but around the world. Of course, he is also the uncontested leader of the Tokaj pack. Szepsy’s is at present the only wine from Hungary in the world market which is invariably met with the utmost admiration, wherever it is served. Most importantly, everyone agrees that he is absolute world record calibre. This is why, as you will recall, he was awarded the title of Les Signeurs du Vin in 2013 at the Villa d’Este, which is practically the Nobel Prize in wine.

Mr Forczek is referring to the award conferred upon István Szepsy in Como, in November 2013, by a body of some of the world’s most prestigious winemakers, including Aubert de Villaine (Domaine de La Romanée-Conti, France), Egon Müller (Weingut Egon Müller, Germany), Angelo Gaja (Gaja, Italy), Alain Vauthier (Château Ausone, France), and Pablo Álvarez (Vega Sicilia, Spain). In a letter written in support of François Mauss, the founder of the prize, these distinguished vintners explain that in the course of history wine has faced, and continues to face today, enormous challenges amidst rampant globalization and the emergence of new markets, and that wine must be regarded not simply as a commercial commodity but as a medium conveying historical and cultural dimensions, and as such its protection and support as a product of human endeavour is an obvious imperative. The explanation attached to the award underlines the historical glory of Tokaj, the devastation that communism visited upon that glory, and the efforts of both Szepsy and the region at large for the past two decades to re-establish a culture-building luxury product.

At present there are a few dozen wineries making high quality dry whites and Aszú in a region where farm work, and particularly the extremely labour-intensive cultivation of vineyards, is shirked by most apart from members of the older generations, and the exodus is growing at an alarming rate. Meanwhile, the wineries still running and fit to produce wines of excellence continue to struggle with sales. The world has turned its back on sweet wines, to the point where consumers have become unable to distinguish artificially fortified sweet wines from the naturally sweet ones that originally made Tokaj famous. As for dry furmint, it is still a newcomer in the sea of wine the world consumes today. It is hardly more of a guarantee than Aszú for the long-term survival of family-owned wineries in Tokaj. Indeed, the recent global crisis has forced Szepsy himself to scale back his own vineyard holdings.

Szepsy’s symbiosis with his vines is a well-known fact in trade circles. He is a man who will probably never be completely satisfied with his own work and achievements. In light

of his character, it is hardly surprising that the geological diversity revealed to him by dry furmint has made him reconsider his views on the potential inherent in the Aszú for some time.

Resuscitated from the ashes in the 1990s, Aszú is a magnificent wine that can hold its own solo, as a separate course served without food at any fine-dining establishment. But István Szepsy would not be the man he is if he did not glimpse in it the opportunity for a paradigm shift, based on a synthesis of his decades-long experiences with this wine style. The notions he is entertaining will take long years to yield tangible results, partly because not every year produces a commercially viable quantity of botrytized grapes, so certain vintages must be skipped altogether. This only shows what a rare gift of nature an Aszú is. The other factor is that a new plantation needs twenty years or so to reach full productive maturity. The contemplated paradigm shift requires specific geological conditions and certain properties of the right furmint clone (compact, loosely packed bunches of small berries). Only when all these prerequisites are in place can a few (long-anticipated) lot-selected Aszú wines be made. These will be genuine rarities, for now exemplified by the 2017 Aszús selected from special parcels in the Szent Tamás and the Betsek, released in late 2020. What message can such a magnificent wine send to the future? We cannot tell for now, except to say that they are veritable works of art, on the order of a piano concerto by Liszt or a painting by Munkácsy. They possess the power to inspire awe and marvel at the Hungarian genius without the obstacles of our difficult language. The way Szepsy sees it, quality has no limit. This is no wonder coming from a man who has long integrated a spiritual vision into the way he lives and operates his enterprise. As he noted earlier in this film, and as he has affirmed in any number of private and public discussions, István Szepsy is conducting a business, but his decisions are never based on mere commercial considerations.

Gabriella Mészáros: He makes me feel I am in the presence of a superior calmness, proper to those who always have a hand to hold, even if his level of serenity is a sphere above mine.

István Szepsy: It is all about resonance, there is nothing but resonance. If you dig down to the heart of matter, you will find nothing but waves of resonance. The most important of them all is the resonance that is human love.

It would be vital for us Hungarians, people with a sense of their Hungarian identity, to remain connected to the land. You are what you consume, and not just in terms of material intake, on the level of trace elements and chemical compounds, but in terms of self-growth. This is what man really needs: to consume products created with love.

Translated by Péter Balikó Lengyel

Images by Gábor Tóth, photographer of the film Stocks of Love