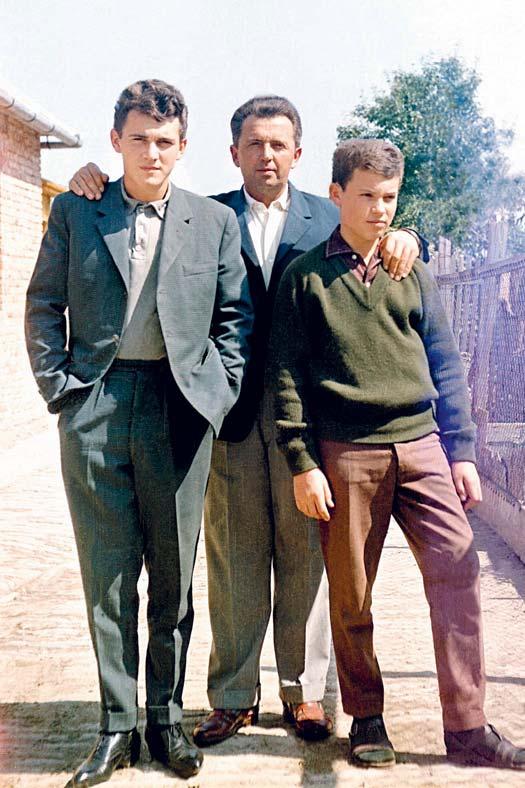

A Portrait of Winemaker Ferenc Takler

Ferenc Takler was born in 1950, during the most hellish period of communism, into a family based in the city of Szekszárd which traced its lineage of peasant proprietors with a consummate mastery of farming going back two hundred and fifty years. However, when he was born as a member of the ninth generation, and for decades thereafter, it seemed that even the last vestiges of the vast knowledge amassed by the family for centuries would be eradicated by the ruthless communist power. At every stage of the first half of his life—as a small child, teenager, and then young father— Takler had to learn the bitter lesson that whatever he and his family started would eventually be turned against them and thwarted by red tape, with the ultimate aim of divesting them of the modest assets they had managed to shore up. Takler’s early life is not unique: the overwhelming majority of farmers in Hungary suffered the same fate, fraught with humiliation. Many perished in forced labour camps; others went insane, succumbed to self-destruction, or left the country. Beyond the human tragedies that continue to haunt families today, an invaluable body of knowledge also fell victim to the communist frenzy. Yet Takler remained one of the few the dictatorship was unable to break. His proactive talent, hard-working habits, and profound religious faith endow him with staunch determination and exceptional stamina. The character of the man is reflected in his outstanding wines and the environment he builds with his sons. Takler’s almost superhuman achievement is corroborated by his friends from all walks of life, who have one thing in common: they have all created something great and enduring.

Attila Vitéz, a keen-sighted and deeply committed local patriot and publisher of several books on the heritage of Szekszárd, decided that the story and exploits of Takler and his sons had to be recorded for posterity. He was the one who proposed that I write a volume of interviews, and the book entitled TAKLER: I Was Always Pushing My Luck … soon went to print. I was more than happy to oblige, as I had nourished a relationship of mutual trust with the family since the first time I met Takler, when he was awarded the title of Winemaker of the Year in 2004. Thanks to the contribution of the typographer Tibor Erky-Nagy, known for his innovative respect for tradition, the attractive volume is now available in a format readily appreciated by the eye trained on digital reading.

In what follows I will augment quotes from the protagonists with historical details, in an attempt to present the life of Ferenc Takler, one of the foremost winemakers in Hungary, and the pinnacles he has achieved in collaboration with his sons.

* * *

FT: From 1949 onward, we were harassed daily and robbed of our assets step by step. My mother’s uncle left the country in 1950 to escape the gallows. Half of the family now lives in Canada. My father was blacklisted as a kulak since he owned about eight hectares of cropland. Today, in 2019, we have seventy hectares of fruit-bearing vines. The last phase of our dispossession came in 1978, when our house, our family home, was taken away from us.

The vehemence with which Takler begins the interview, as we are seated in the main hall of his elegant manor house, speaks of a man eager to spill all the anguish and bitterness visited on him across decades.

FT: My father was constantly hounded, arraigned, and hauled over the coals. They kept telling him he would be removed from the kulak list if he relinquished his vineyards. He was reckoned to be a man of independent mind who stood out

from the rural world around him. He had to be watched. My father would tell us to always hold our heads high, no matter the odds. This was his motto. He was a tech school graduate, a man of common sense and resolve whose word carried weight. No wonder he was stigmatized as a ‘class alien’. He never found favour with the communist authorities, to put it mildly. It made no difference when he offered to hand over to the state the newly planted olaszrizling vineyard in Alsóbakta, in the hope that in return he would finally be left alone. Barely a week later he saw his name on the kulak list again. And this went on and on. We lived in constant terror. I cannot begin to tell you about the daily humiliation and stress of having to share your lunch or dinner with political agitators. They would sit at our table until nightfall. They wouldn’t stop pestering us until my father agreed to join the local co-op. Then, in 1964, they appropriated a wonderful farmstead property from my Neiner grandmother. I was fourteen at the time. I was walking home from school on a fine September morning and saw a digger uprooting her vines loaded with ripe black fruit. They didn’t even have the decency to wait until harvest time. But our deprivation didn’t end there. The state farm was organized in 1965. They knew that our estate comprised several holdings scattered around Szekszárd, so we were always in the way. The next one they set their eyes on was our Róka Vineyard, a one-and-a-half acre [about 0.6 hectare] parcel with a beautiful farm building, some of it planted to olaszrizling and kadarka vines and the rest consisting of my grandmother’s vegetable garden from where she sold her produce in markets to feed her three children. This whole property was taken away from her.

FT: Up until 1960, my mother would send me to the local store for four things only: salt, sugar, yeast, and chicory Ferenc Takler’s grandmother with her daughters Erzsébet and Rozika

coffee substitute. We grew or made everything else ourselves: bread, lard, peppers, butter, farmer’s cheese, sour cream, meat, you name it. My mother would mix the dough using our own flour, cover it with cloth, then tear it into loaf-sized lumps. In the morning, when the dough had risen, I would put it all in a large wicker basket and bring it to the baker to bake. Small kids of six or seven, like myself at the time, were routinely dispatched at dawn to deliver fresh milk to neighbours in the street. We processed most of our milk, though, making butter and farmer’s cheese. My mother continued to bake our own bread after 1960, but by then we were buying the wheat for it, and all our livestock and horses had been seized by the co-op.

As was the custom in rural society those days, Ferenc was put to work as a young boy, sent off to the dark of the cellar, candle in hand, to de-eye potatoes or, a few years later, to work as a day labourer stacking hay by the machine. Around 1968, when the communist regime seemed to relax its stranglehold on private property and efforts were made to restore the frayed prestige of market gardening, the emboldened Taklers started to husband pigs and chickens. The local party potentates, however, never left them alone.

FT: The system was so corrupt—taxes were assessed by estimation—that the profit they determined was the multiple of what we actually made. The comrades singled us out, and we even went to court about it, but the judges ruled against us. My father quit it all, pigs and chicken, the works. All we were left with was a tiny vineyard to our name. It was for a reason that the communists bent over backwards to eradicate the traditional self-reliant lifestyle of the peasants who nurtured a symbiotic relationship with the land they cultivated. Takler puts it this way:

FT: The farmer knew how to do almost everything himself, he didn’t need anyone’s help. He couldn’t be misled. All his thoughts revolved around the farm, the machines he knew well, the seeds he had to sow, the animals he tended to. He would never hire consultants or agrochemists. He produced his own seed and knew plant diseases intimately. He was a complex man. This was what made him a threat in the eyes of the bullying communist gang. They never managed to deter me from my work, but they did leave a mark.

Takler was sixteen when he woke up to the potential of life as a wine grower and decided to prove to his forebears that resurrection was possible.

FT: I was kept going by my love of the land and respect for the wine. As a sixteen-year-old, I realized that the kadarka grape had no name, and was vastly underestimated. At that time, I vowed to devote my life to changing that, no matter what it took. Then I had my first own harvest, in a vineyard my father had planted in 1964 for me and my older brother. As I cultivated it, I got a taste of the proprietor’s pride, the sense of being in control of one’s own wine. I had a nine-hectolitre barrel stock full of my own wine! I was in heaven. I tapped it, treated it, and sold it retail. Earned a little money. The following year we tilled that vineyard again. I began to lay the cornerstones of cultivating and managing my own estate. It felt good. I enjoyed doing it. You cannot break a Swabian.1 The Swabian wants to stay alive. He is frugal and hard-working. They couldn’t even break us in 1978, when I was a young father holding my year-and-a-half old Andris on my arm, watching our house being taken away from us, along with the backyard, farm buildings, and pigsties. We were relocated to a flat in a concrete block. We didn’t mind that downturn in living conditions so much as we worried about the fate of the press, casks, vats, and all the other assets we used in running the farm.

The family of Ottó Légli, the renowned grower in the Balatonboglár wine district south of Lake Balaton (who serves as President of the National Council of Wine Communities) was also tormented by the communists. He has been a close friend and comrade-in-arms of Takler’s for decades.

OL: Feri says we get along as well as we do because we both went through similar things at roughly the same time. My family had almost half a hectare of vines ‘nationalized’ in 1975. It was a relatively new plot my father had planted, encouraged by the New Economic Mechanism introduced in 1968. He was confident he would pull it off, but the comrades disregarded their own new laws and descended on us. It was all very hard for my father, who had seen his family ‘blasted out’ of its property three times in less than three decades. […] In our corner of the world, here in Transdanubia, everyone had his own ‘hillside’, as we say. Men not yet old enough to marry would already have a share of cellar space. They instinctively brought from home their palate for food and wine. Good taste was evident in gastronomy and local architecture. Just look at those old press houses among the vineyards in the hills. Then communism came and the landscape was desecrated by unspeakable buildings. The peasant of the old days amassed a huge storehouse of knowledge. My great-grandfather had only primary school education, but he knew beauty when he saw it. He made his own tools, and had a way with plants, crops, animals, and wine. He fed five or six children. The women worked all day without the benefit of electricity or household appliances. On Sunday, they went to hear Mass, accompanied by children dressed in meticulously ironed white shirts. Rural culture thrived on this enormous body of expertise and heritage, handed down from one generation to the next. My great-grandfather had lived his life out on the hill as a free man. Unlike house servants, who had a reliable stipend based on precisely kept books, free peasants always ran risks. They were in possession of a broad-ranging, profound knowledge base, which was their only strength. It was this powerful group that the communists aimed to destroy in a deliberate manner. Because they were afraid of them.

Another family in Szekszárd with Swabian roots are the Eszterbauers, growers and winemakers for generations. Like their peers, they were not spared by the decades of communist depredation. János Eszterbauer, another good friend of Takler’s, resuscitated his family legacy later in life, establishing his own winery after he had consolidated his venture in the machine industry. He has this story to tell:

JE: I had nothing left of the once flourishing family estate. They had grabbed it all. This meant a massive moral and material loss for the family. The despair of being dispossessed caused many tragedies on the paternal side. My maternal grandfather agreed to join the co-op through gritted teeth. I remember when they came to take his horse away. He chose to send it to the slaughterhouse rather than to have it end up in their hands. At three years old, I was the last person to ever ride Csillag. My father slowly merged in with the co-op and was eventually appointed cellar master. My family had to toe the line unless they wanted to starve to death.

The uprooting of the traditional rural way of life, aggressive industrialization, the defacing of Szekszárd’s architecture, and the campaign to cram Swabian and southern Slav Hungarians into concrete blocks of flats damaged the entire historical wine region in ways that are still being felt today. To add insult to injury, the communists even denied the town the right to continue to label their top red blends under the famous bikavér brand name. It was from this state of having been bled to death that Takler and his friends, like other growers in Szekszárd and indeed the entire community of winemakers in Hungary, had to resurrect themselves and their trade after the Iron Curtain finally came down.

Ferenc Takler is a qualified machine technician by trade. Adapting to the exigencies of communism, he rose to be manager of the state-owned Construction and Forwarding Company in Szekszárd, but could hardly wait to strike out on his own. He responded instantly to the slightest sign of market relaxation that preceded the fall of the communist regime, buying light farm machinery and pouncing on every opportunity to buy a plot of land. He focused on improving efficiency in vineyard work and on achieving superior wine quality. At first, he sold his wines in taverns, but soon began to deliver to restaurants in Budapest.

FT: To think of all the effort I put into it, by myself … I would load my small trailer with forty crates of grapes, then do the destemming and pressing all by myself. I knew that if I turned the pump on I had to run to make it to the nozzle of the hose by the time the must arrived, so that not a single drop would go to waste. All this knee-deep in mud. Then I upended the tanker so that it was parked almost vertically, and goosed the must straight down into the cellar using gravity. I had no help. None. The kids were still in school, after all.

Following the democratic turn, the first freely elected Hungarian government did not return the properties seized by the communists directly to their rightful owners, but chose instead to issue so-called compensation notes to them. The awkwardness of the solution and the extent of the havoc the communists had wreaked are indicated by the fact that most of these

compensation notes ended up in the hands of beneficiaries who had long severed their ties with the land and had no desire to return to the farmer’s life. Under the circumstances, Takler—who, by contrast, wanted all the land he could get—had to act bravely to obtain compensation notes in the quantity he needed.

FT: I took the wildest, craziest risks just to bid. One day I offered fifty-six thousand forints for what was then a plot of mud. I didn’t stop bugging the owner until he handed his notes to me. I promised to pay him on a short deadline. Two days before the agreed date he called me. I told him he would get his money on time and hung up. My wife was crying. Two days I needed to be comforted myself. And then help from heaven came. The phone rang. It was a client placing an order for wine worth exactly fifty-six thousand! This was a miracle. The largest order I had had before was thirty thousand at the most. This one would go for fifty-six, and they wanted it delivered the following morning!

This was not the only time that Takler courted disaster to achieve his goal of rebuilding his family’s wine estate. As he puts it, he always pushed his luck hard, in an effort to complement

his wines—which turned out finer every year—by offering food and accommodation to match, attaining the highest standards of hospitality by 2021. It was an enterprise of massive property development in which he could always count on his sons András and Ferenc. He pressed a hoe in their hands well before they were ten, and they obeyed their stern father, helping out wherever they could. It was this collaboration between father and sons which guided the family enterprise onto the path of premium quality wines in the 1990s. Planning for the long haul as demanded by the very nature of growing grapes and making wine, and seeing the change of generations around the corner with a keen sense of timing, Takler steered his sons with consummate skill over a sea of career choices and assignments tailored to their respective talents. This is how first-born András became the estate director responsible for marketing, communication, and representation, while Ferenc Jr distinguished himself in viticulture and enology.

After the initial streak of well-earned success, Ferenc Takler was awarded the highest wine industry honour in Hungary. András recalls his father’s acceptance speech in these words:

AT: When Dad was elected Winemaker of the Year in 2004, at the award ceremony he started his speech by saying, ‘It is not my success alone, my sons have a major share in it. Ferenc has put in his shifts in the cellar, András in marketing and the rest of the business. We have always made a fine team, despite a few inevitable conflicts once in a while.’

Szekszárd’s own famous grape is the kadarka. Ferenc Takler is convinced that this grape variety was responsible for promoting the town to the status of county seat. As kadarka is a finicky and labour-intensive variety, it virtually disappeared under the mass production ethos of the state co-op era. The Taklers were the first to pick it up again in an attempt to

restore the grape to its former glory—a vow Ferenc had made as a young man. Also, they took bikavér, the district’s famous red blend, very seriously from the outset. Cellar master Ferenc Jr has this to say about the vision they first had over two decades ago:

FT Jr: Unlike others, we focused on kadarka when we began to plant in 2000. We had this gut feeling that it was unacceptable to let kadarka fall by the wayside, and we did sense a certain market demand. We continue to devote a lot of attention to the grape. Its sensitivity to rot makes it a difficult proposition for the winemaker. Bush training used to be the norm back then, but now we train it on the high cordon and the umbrella as well. The old folk used to say that bush training was the only way to go, but it’s not true. It’s just that kadarka did not tolerate industrial methods and responded by producing inferior quality. But when it’s pruned selectively and the yield is kept low, it can make a fine, pure-flavoured wine. We would argue endlessly with colleagues about the true nature of the kadarka. Today, nothing can be labelled Szekszárd wine that has not been passed by a jury we elect from among us. The aim is not to release a single bottle of wine unless it has typicity and varietal character as well. The hallmark of kadarka is its spice, this is what makes it unique. Whenever I open a bottle of kadarka, I usually have fisherman’s soup on the table, and I immediately look for that sophisticated spiciness to match it.

It took many years of hard work and Ferenc Takler’s widely respected probity of character to forge a solid community of Szekszárd growers whose wines speak for themselves today. The region-wide cooperation yielded important results, such as renewed interest in the kadarka and kékfrankos varieties, or the new Szekszárd wine bottle design which guarantees premium quality for the consumer. That the Taklers have the touch of the virtuoso with the kékfrankos as well is shown by their range using this grape, from a light table wine to an estate flagship bottling. Károly Áts, former winemaker for Royal Tokaj, lauds the latter wine in my book as follows:

KÁ: The Taklers’ kékfrankos selection named Minden 50. évben (Once in 50 Years) is a miracle. If such miracles exist, we had better believe they will come round more often than that. Yet here we are pusillanimous, even as we know that Hungarian wine was once one of the hardest currencies around.

As I have emphasized before, the effects of the communist devastation remain with us today. The centrally forced urbanization deprived Szekszárd of its most precious vineyards. Yet the city continues to expand and reclaim sites from the vines. As Ferenc Jr points out:

FT Jr: The Porkoláb, the Baranya, the Őcsény, the Decsi are all succumbing to new construction step by step. I have asked all the other growers, how much longer are we going to take this? We can’t just retreat to the next valley, because there you cannot make the kind of great red wine Szekszárd is destined for. If we fail to declare protection for these sites, the whole wine district may go down the drain.

A part of Hungarian tradition, wines labelled bikavér can be made only in Eger and Szekszárd, according to regulations approved by each wine region. The Szekszárd bikavér was the pet cause of the Taklers long before the local community reached an agreement on the composition of the blend. Today, more than 50 per cent of bikavér must come from varieties unique to the Carpathian Basin (kékfrankos and kadarka). Everything else must take second place, and that applies to cabernet and its compatriots. Ferenc Jr explains:

FT Jr: The bikavér should be a national cause and a time-honoured tradition, but it has been corrupted and abused. When we made our first, there was instant demand for it. It takes a long time before a blend of five or six varieties comes into its own and reveals harmony. My ideal bikavér is a stylish, rich, complex, but easy- drinking red whose precise inner proportions are dictated by the given vintage. It’s a particularly soft spot for the Hungarian consumer. We make bikavér in the premium category only.

Takler’s character and performance are reflected by the friends he keeps, some of whom are outstanding and internationally recognized masters of their own trade. The neurobiologist Dr Tamás Freund, recipient of the 2011 Brain Prize and President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, counts himself among them. He befriended the Taklers in the mid-1990s, during the halcyon days of the Hungarian wine renaissance. As Professor Freund recalls:

TF: I was introduced to Ferenc by winemakers based in Villány. Our fields of interest could not be further apart. He is a sports fan, a former soccer player. In my life, the formative passion apart from my profession has been music. Yet we struck up this intimate friendship, perhaps because both of us regarded the international vanguard as the yardstick to live up to in our respective trades, and by doing so, we wanted to bolster the reputation of our country. This is what I myself wanted to achieve all my life, so it’s no wonder I have had nothing but the deepest respect for winemakers who do not chase profit in the first place, but rather the pinnacles of quality in what they do, and want to elicit a response from the world. Ferenc Takler is one of those people. […] I have no doubt in my mind that the last Renaissance profession is that of the winemaker. During the Renaissance, it was natural for a scientist to be a bit of an artist, and for an artist to be a bit of a scientist. Like Leonardo de Vinci. The winemaker has recourse to many scientific disciplines, including breeding and clone selection, growing technologies, soil analysis, and so on. Yet a wine made with nothing but sheer scientific precision will never be anything more than a simple commercial product. A wine can only be truly good and a source of pleasure if it reflects the personality of its maker. And this is where the artistic aspect comes in, because a winemaker’s character will not be truly rich unless he manages to transmute and convey through his own person the traditions of his nation and narrower region while expressing the depths of his own emotions and sentiments. The winemaker par excellence in my view is the one who can afford a glimpse into both of these worlds through his wines. Ferenc Takler and his sons are like that.

Tamás Freund’s deep commitment to the cause of Hungarian wine is evident in his actions, not just in his fine words. He has organized blind tastings for his research colleagues and invited guests to Hungary to gain a first-hand experience of the country’s wines.

TF: Barry Everitt, former dean of Cambridge University, once accompanied me on a trip to the Taklers, and became so enchanted by the family (and also by winemakers in Villány, Tokaj, Balaton, and Eger) that he invited them to Cambridge for a presentation. Incidentally, Everitt chaired the committee in charge of procuring wines for every college of his famous university. He introduced his estimable colleagues to Hungarian winemakers and their wines. I can say without exaggeration that they swooned. The last thing they expected from Hungary was wines of this calibre.

The Cziffra Festival was launched in 2016 and has since become increasingly popular in Hungary. The Kossuth Prize laureate pianist János Balázs was inspired to mastermind

the festival by the work of György Cziffra, the great virtuoso of his own instrument, who had left his native Hungary during the 1956 Revolution. Seeking to enrich this major musical event through gastronomic delights, Balázs was putting the finishing touches to his plan when he was introduced to the Taklers by Tamás Freund. The mutual sympathy between them soon developed into earnest collaboration aimed at creating the festival’s official wine, dubbed Rubato. The artist begins to relate the story by retracing his steps in music history.

JB: Szekszárd wine was Franz Liszt’s favourite, and because his music is so readily associated with the mastery of György Cziffra, everything seemed to suggest that I had to get to know the Taklers. As Ferenc showed me the estate and we began to talk at length, I instantly sensed great human stature and intelligence. There and then, the question of the ‘Cziffra wine’ was settled. The result is the Rubato, a red blend based on an equal proportion of the dazzling syrah and the local hero, kékfrankos, augmented with some merlot and both cabernets. The actual work of blending was performed in the presence of the three Taklers, Tamás Freund, and myself. Rubato is a term of musical interpretation which means expressive freedom employed by the performer of a piece. As such, it befits the style of both Cziffra and this wine perfectly.

Liszt resorted to a synesthetic metaphor when he once said he wanted more blue in a piece of music. Reversing the image, this is how János Balázs describes what the ideal Szekszárd wine means to him:

JB: I associate Szekszárd wine with a velvety, smooth, and warm sound playing mostly in the higher registers, which is neither too soft nor too strong. It is comforting rather than overwhelming, like an elegant velvet armchair in which it feels wonderful to cuddle up. It has a firm spine and a festive mood. For me, Szekszárd wine is like Rachmaninov among the great composers, despite his profoundly Russian soul. It is masculine yet generous, lush and emotional, without ever becoming trite or flattering. Take the first sip or listen to the first note, and you will be enveloped in an emanating warmth.

After decades of indiscriminate taste and mass production, the winemakers of Hungary, and thus the Taklers, have been granted less than the span of a generation to get back on their feet, survey real market demand, and adopt the latest technologies in the vineyard and the cellar, while safeguarding the traditions of Hungarian wine in general and Szekszárd wine in particular. The Taklers made a long journey, sometimes straying off into blind alleys, before they arrived at the finely honed style that is the hallmark of this family and that of genuine Szekszárd wine. Ferenc Takler sums up the birth of a great wine eloquently:

FT: The secret of the very best you can get out of that handful of grape varieties lies on the palate. It cannot be put into words. You must feel it. I only feel relaxed— and this is true of my sons, Andris and Feri too—we only get along with the wine we have made when we know we have done everything possible, as professionals and human beings. Looking back at our 2006 Cabernet Franc Reserve, or the 2007 Regnum, when we said that’s it and gave them the green light, I predicted they would be a success. And they were. I am not sure I can conjure that kind of magic any day or any year, but I always set my sights on the very best I can achieve under the circumstances. The rest is up to the gods.

Translated by Péter Balikó Lengyel

1 Hungarians used the term svábok (Swabs) to designate ethnic Germans settled in Hungary in the eighteenth century, although not all of them came from Swabia. A few generations later even ethnic Germans referred to themselves as svábok, without respect to the place of origin of their ancestors. (The editors.)