Overview of György Matolcsy’s Economic Balance and Growth 2010–2019: From the Last to the First

SUMMARY

Certain works exploring the cultural history of mankind describe the living, regenerative economic organization of a country as a sort of ‘botanical garden’. György Matolcsy, former minister of the economy and current governor of the Hungarian National Bank (MNB), has written just such a book about Hungary. It shows the outstanding performance of the Hungarian economy, in terms of catching up with other European economies, during the years 2010–2019, while also looking back over the broad trajectory of the last century. Using an interdisciplinary method of analysis, it comprehensively outlines the social and economic support and stimulus drivers, as well as the conditions that have enabled the Hungarian economy to perform so well. Another valuable aspect of this encyclopaedic book is its presentation of the innovative economic policy approach taken by the government, with its dynamic, sustainable model, and new institutional system, which was able to generate effective responses to the challenges created by the international financial and economic crisis of 2008–2009.

SUCCESSFUL CATCH-UP

In an earlier volume, the author described the Hungarian economy during the two decades between 1990 and 2010 as characterized by failures and missed opportunities. The ‘balance or growth’ dilemma emerged periodically, with varying degrees of severity, from the early 1960s on: economic growth led to a deterioration in foreign trade and budgetary balances, while government adjustment measures taken to resolve this subsequently slowed down or stopped economic growth, which was repeatedly the case in the planned economy which existed until 1990. Similarly, in the 1990–2010 period, the Hungarian economy was characterized by a situation in which either indicators of balance developed unfavourably due to the structure of economic growth, or else growth was hindered by efforts to restore economic equilibrium. This became particularly acute during the 2002– 2010 period, when Hungary went from regional front-runner to laggard.

The impact of the international financial and economic crisis of 2007–2009 forced the country to overcome these ingrained failings, and the political turnaround of 2010 provided an opportunity to do so. This turnaround was so extensive and efficient that another work covering the economic history of post-Trianon Hungary, published last year under the auspices of the MNB, rightly calls the last ten years the most successful decade of the last hundred years.

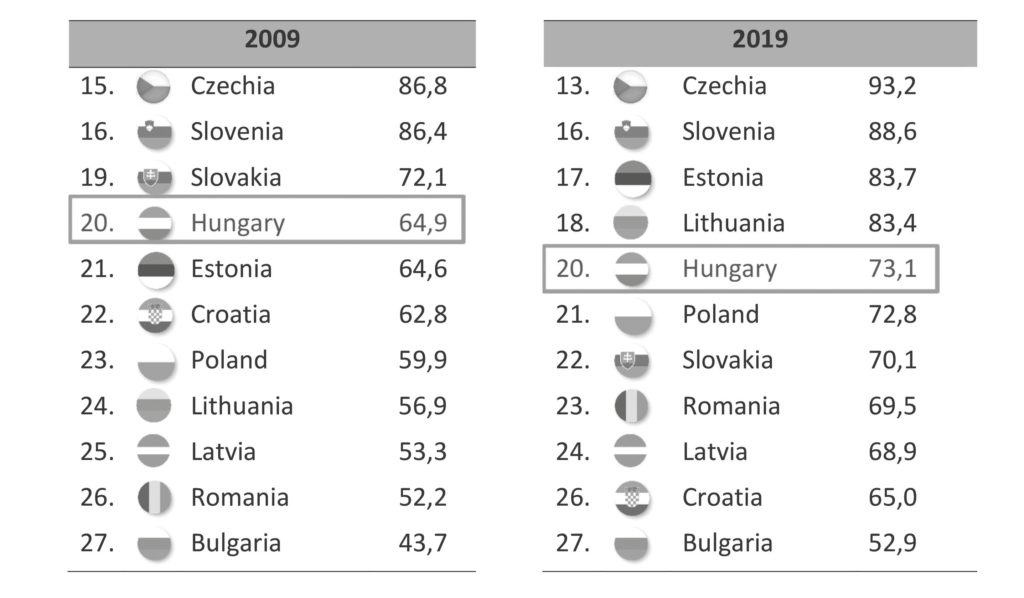

The second, updated edition of Economic Balance and Growth 2010–2019: From the Last to the First (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, 2021) shows that by 2019, Hungary’s GDP was 8.2 percentage points closer to the EU-27 average level of development compared to a decade earlier. This meant that Hungary had overtaken Greece, and had once again surpassed Poland and Slovakia. The volume published in 2019 naturally does not include 2020 data (or the statistical revisions carried out in the meantime), according to which Hungary continued to catch up in 2020, reaching 74.4 per cent of the EU average, though several Central and Eastern European countries advanced more rapidly than Hungary.

The author rightly emphasizes that Hungary’s economic performance over the past decade truly stands out among all EU economies. This is due to the following qualitative changes underlying the effort to catch up:

- The employment rate rose from 55 per cent, the worst score in the EU-27, to 70 per cent between 2010 and 2019.

- The Hungarian economy achieved the best labour market performance among EU states between 2010 and 2019. The unemployment rate fell below 4 per cent, the fourth lowest in the EU in 2019, bringing Hungary close to full employment.

- The Hungarian investment rate increased from 20.1 per cent to 27.1 per cent between 2010 and 2019, and in 2018–2019, investment accounted for nearly three quarters of economic growth.

- The government debt ratio has fallen by 15 percentage points in ten years, which is among the top four best performances in the EU.

- The general government deficit as a share of GDP was below 3 per cent between 2012 and 2019, meaning that Hungary is no longer at the bottom of EU rankings in budgetary terms; the previous period had been characterized by continual excessive deficit procedures.

- The current account was in the 0+ range between 2010 and 2018, in contrast to the long twin-deficit period which preceded it.

- With the conversion of Swiss franc loans taken out by many households into forints, a budget deficit of less than 3 per cent, declining public debt and a balance of payments of around 0+, Hungary left the group of the ten most vulnerable countries in the world economy, which is where it had been in 2010.

Based on these results, the author states that in the period under review Hungary caught up with the region, and even became the regional leader in several important respects. It is rightly stated, therefore, as a subtitle of the book, that the country has gone from being the ‘last’ to the ‘first’ once again.

REFORMS, STIMULI, AND TURNAROUNDS IN TRENDS

According to the author, Hungary was able to achieve these results, as well as the necessary stabilization and consolidation, because the government’s goal was not simply to restore financial balance in the short term, but to launch profound structural reforms, in contrast to the periodic bouts of austerity inflicted by former governments. Economic policy following the new value system is largely built on bold, innovative, non-conventional instruments.

The conditions and drivers of success are presented by the author through multifaceted, high-level analyses. One of the most important of these is the discussion of the view held by the governing party and several economic analysts in 2010 that the restructuring of the economy should be based on the creation of jobs (one million new jobs). This made it possible to effect a series of economic and monetary policy turnarounds in the 2010–2019 period. The key economic policy developments were as follows (the data may have changed since the publication of the book):

- Labour market: large-scale employment expansion (2010: 3.8 million employed people; 2019: 4.6 million employed people).

- Tax system: shifting the focus of the tax system from taxes on labour to taxes on sales.

- Incentivization: a reduction of the marginal tax wedge on labour income (2010: 64.1 per cent; 2019: 44.1 per cent).

- Public finance: reduction of the budget deficit (2010: –4.4 per cent; 2019:

–2.1 per cent of GDP).

- Government debt: reduction of gross government debt (2010: 80.2 per cent of GDP; 2019: 65.5 per cent of GDP).

- Exit from the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) in 2013.

- Monetary policy: reduction of the base rate (2010: 6 per cent; 2019: 0.9 per cent).

- Lending: ending the credit crunch, achieving growth in corporate loans (2010:

–2.5 per cent; 2019: 14.0 per cent annual growth rate).

- FX loans of households: derecognition of foreign currency loans to households (2010: 65 per cent; 2019: 0 per cent ratio of retail loans).

- MNB balance sheet: narrowing of the MNB balance sheet as a share of GDP (2010: 37.2 per cent; 2019: 26.4 per cent).

- Growth: achieving renewed GDP growth after a protracted recession (2010:

1.1 per cent; 2019: 4.6 per cent GDP growth).

- Catch-up: growth above the EU average (economic growth 2 per cent above the EU average between 2013 and 2019).

Among the monetary policy developments, the following are particularly noteworthy, in addition to the low base rate:

- The introduction of the Funding for Growth Scheme (FGS) in 2013 put lending to small and medium size enterprises (SME) on a double-digit growth path.

- Repatriation and a tenfold increase of the gold reserve: the central bank rebuilt the domestic gold reserve (in 2021 the central bank tripled this figure again, thus increasing the foreign exchange reserve to thirty times its former total).

- Uniquely in the world, Hungary has succeeded in fully introducing an instant payment system that increases the speed of money transfers significantly.

- At the request of the government, the MNB developed a competitiveness strategy.

- Between 2017 and 2019, the MNB met its inflation target almost every month.

- Turnaround in profit: the new management of the MNB has been achieving significant positive profit year after year since 2013.

- Financial assistance for coronavirus crisis management in 2020: the MNB provided excess liquidity to the banking system, supported the loan and repayment moratorium, increased foreign exchange reserves, expanded and restarted the FGS, continuously stabilized the government securities market, and used its resources to help with the investment-oriented growth turnaround.

As the author points out, another important condition of the new economic policy was its internal identity: a balanced budget should be achieved without austerity, thus it would not be through the reduction of expenditure but through increased revenue that the public finance position would be improved. However, this increase in revenue would not be achieved by raising taxes, but by stimulating employment, widening public burdens, and whitening the economy, which would allow for tax reductions in key areas. Shifting the focus of the tax system from taxes on labour to taxes on sales has encouraged employment and reduced the distortionary effect of the tax system as a whole. As this reorganization had a short-term revenue- reducing effect, it was necessary to extend the burden to sectors with higher carrying capacity but lower taxes (in the form of temporary, targeted special taxes) and to activities in the grey economy. The efficiency of tax collection has been improved primarily by the introduction of the online cash register system. In the long run, the realignment between labour and sales taxes has already financed itself, as the stimulating effects of the reform have increased the tax base.

The effects of the new system of taxation, which expresses the main direction of economic policy, have played a decisive role both in restoring balance (especially to the government budgetary position) and in stimulating economic growth and employment.

Tax reform has also contributed to the growth of trust capital. Previously, low employment figures and widespread tax evasion suggested low levels of trust capital. High tax rates reduced employment, incentivizing free riders and those working in the grey economy, with consequent damage to social cohesion. Post- 2010 tax changes have encouraged employment and increased legal incomes, and this wider burden-sharing has strengthened public confidence.

Another successful achievement of the last decade has been the implementation of numerous and effective structural reforms. As many as 50 reforms were implemented during the period in question. Hungary has followed the experience of successful countries, which implemented their reforms without delay and in a concentrated manner in order to exploit the synergies between them. Therefore, in the first three and a half years of this period—i.e. by the end of 2013—43 major reforms had been implemented or launched, the most significant of which include:

- Tax reform, the introduction of a bank tax, a targeted temporary crisis tax on high-capacity sectors, small business tax cuts, the opening towards the East, and reducing the number of economically inactive people (2010: 6 reforms).

- The introduction of public employment, the possibility of preferential final repayment for families with foreign currency loans, the new Fundamental Law, increasing the weight of green taxes, the New Széchenyi Plan to support businesses, discounted cafeteria in the form of the SZÉP Card for employers, constitutional debt rule to reduce public debt, dual training, family tax relief, expansion of state assets, the Széll Kálmán Plan for the structural reform of public expenditure, and reform of private pension funds (2011: 12 reforms).

- Budget turnaround, the repayment of general government foreign currency debt in forints, the renewal of the residential government securities strategy, innovative planning for the EU budget cycle 2014–2020, achieving a surplus in the primary budget balance, 60 per cent of EU subsidies for economic development, strategic agreements with key companies, flexible student loan formats, an exchange rate barrier to protect families with foreign currency loans, reform of the Labour Code, reduction of public debt (2012: 10 reforms).

- Monetary policy turnaround, introduction of a toll proportional to the distance travelled in the freight transport sector, introduction of the Funding for Growth Scheme by the MNB, introduction of online cash registers to increase tax collection efficiency, repayment of the last tranche of the IMF loan, a new land law, the beginning of education reform, central debt assumption of local governments, completion of crisis management with sovereign assets, expansion of free enterprise zones, introduction of a financial transaction tax, reduction of taxes on labour for targeted groups as part of the Workplace Protection Action Plan, integration of financial supervision into the central bank, termination of EDP procedure, a reduction in the cost of overheads for families (2013: 15 reforms).

Regarding the critical quantitative and qualitative reforms, the author notes that Hungary benefitted from the implementation of concentrated, wide-ranging changes, instead of adopting the practice prevalent in pre-2010 Hungary, as well as in the southern states of the Eurozone, of introducing only gradual and piecemeal reform, and only after a series of progressively larger trials.

The book also provides a comprehensive overview and analysis of the impact mechanisms of the central bank, especially regarding the monetary policy turnaround. This shift—effected under the direction of the author, György Matolcsy—was launched by the MNB in the spring of 2013 and implemented in a series of steps through to the end of 2019. These included: lowering the price of money while maintaining price stability, facilitating access to credit, extending the term of credit, increasing the availability of resources for business and family investments, encouraging savings, financing the national economy from domestic sources, establishing new areas in the internal financial market (for instance the capital market), and strengthening competition throughout the entire Hungarian financial sector.

Central banking experts have calculated that these initiatives may have accounted for as much as half of total GDP growth between 2013 and 2019, while helping to maintain fiscal balance through lower interest on government debt and revenue from increased growth. After the balance turnaround between 2010 and 2012, there was a growth turnaround and then a catching-up turnaround starting from 2013, because the MNB programmes supported the government’s measures and a strategic alliance between the government and the central bank was formed.

The author emphasizes the importance of coordination between internal and external resources as being among the most important conditions and driving forces determining the performance of the Hungarian economy. He notes that in the 2010–2019 period, new internal sources helped bolster GDP growth at least as much as external sources (EU funds, inflows of foreign direct investment), contradicting the view that most or all of the support was attributable to external factors.

The MNB’s programmes supplied HUF 12,400 billion in financial resources to the economy between 2013 and 2019. Of this, the budget’s interest savings were HUF 3,600 billion, the private sector’s interest savings HUF 3,500 billion, the Funding for Growth Scheme HUF 3,200 and the conversion of foreign currency loans HUF 2,100 billion. The total Hungarian budget for the 2014–2020 EU budget cycle was about HUF 11,000 billion.

This financing success is the result of decisions taken in the realm of politics and economic policy, especially monetary policy, as access to external resources would not have been possible had past imbalances continued. The author also points out, with the example of Hungary, that the key to solving the problems of financing development is to be found in internal sources, as the efficiency of external sources also largely depends on them.

In addition, a stable and growing economy has generated confidence among foreign investors. Between 2009 and 2011, the inflow of working capital through foreign direct investment was only €4.5 billion (an annual average of only €1.5 billion). The recovery from the crisis and the restoration of macroeconomic balance strengthened foreign investors’ confidence in Hungary, which was reflected in the dynamic inflow of direct capital investments. As a result, the inflow of direct investment rose to several times the levels seen during the crisis and exceeded €31 billion between 2012 and 2019 (an annual average of almost €3.9 billion), the highest as a ratio of GDP in the entire East Central European region.

Among the factors explaining the successes of the past decade, we should not discount the importance of the fact that political, economic, and monetary policymaking has been carefully adapted to the fluctuating shifts in manoeuvring room. Thus, by adapting to the restricted manoeuvring room which resulted from the 2007–2009 crisis, and which still pertained in 2010–2012, then, from 2013 onwards, focusing on expansion, growth, and catching up, Hungary was able to take advantage of the opportunities offered by seven good years. The tenth decade of Hungarian economic history after 1920 was successful because, according to the author, the country made good use of the most important resource: time!

ECONOMIC POLICY SYNTHESIS

The economic and economic policy results outlined above could not have been achieved without the Hungarian value system orientating both communities and individuals, without, as György Matolcsy emphasizes, the spirit of competition, the desire for harmony, growth, and the presence of truth. The idea and the construction of a work-based society opened the door to a spirit of competition, generated prosperity, fairly distributed burdens, and thus strengthened social harmony. Over the past decade, the state, politics, and governance have all operated in this spirit.

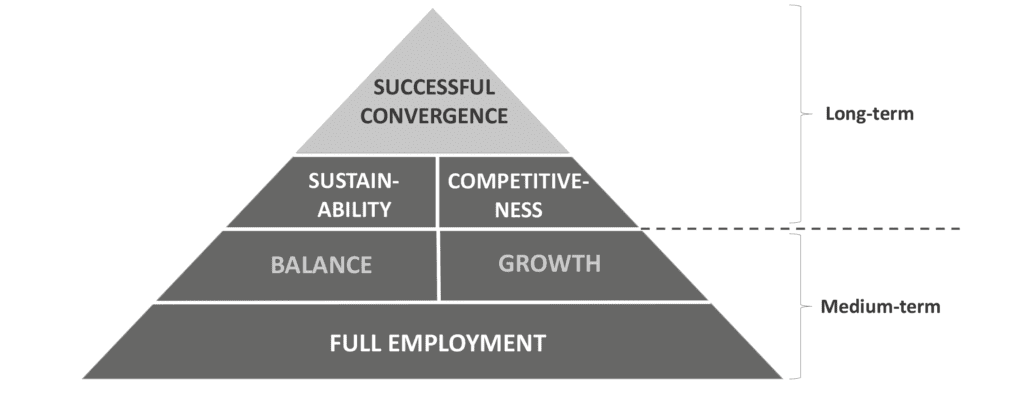

The other, economic side of the economic policy synthesis outlined in this book— in contrast to the ‘balance or growth’ approach—was based on the ‘balance and growth’ plus employment equals sustainable balance approach, on the basis of which action programmes to ensure that that balance remains sustainable can be built.

Though the book deals with economic policy during the 2010–2019 period, its central messages are also valid for the longer term: just as the country can, in the medium term, successfully catch up economically by virtue of a strategy of balance and growth, the same principles can ensure its sustainability and competitiveness in the long term.

Hungary should continue to pursue the types of economic policies that have proved so successful over the last decade, while of course adapting to the requirements of

the new decade. The big challenge is to maintain balance and growth in the long run. The requirements of sustainability must be met in order to maintain balance over decades. Sustainability can assume a number of forms: ecological, financial, social, and economic sustainability must be achieved at the same time. Should any single pillar of this system fall, the complex balance would be upset. On the other hand, long-term economic growth requires competitiveness. Competitiveness is about anticipating economic growth: whoever is competitive today is also assured of economic growth for several years to come. Just like sustainability, competitiveness is a very multifarious concept, since it must cover not only the competitiveness of the economy and individual companies, but also that of the state and human capital. If similar developments take place in Hungary in the fields of competitiveness and sustainability as we saw in the areas of balance and growth in the early 2010s, then Hungary may be among the winners of the 2020s.

Translated by Thomas Sneddon