After thorough consideration of the Latin dictum ‘books have their own destiny’ (habent sua fata libelli), I concluded, somewhat ironically, that it is not only true of books, but of book reviews, too. 1This text is the edited version of the presentation delivered at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences on 29 November 2018, the Day of Hungarian Science. As the author is not a member of the guild of art historians specializing in medieval art, how and why he had the courage to undertake the task of presenting this collective English monograph published in Rome on medieval art in Hungary—perhaps the most significant venture in this field in the last decades—warrants explanation. 2Xavier Barral i Altet, Pál Lővei, Vinni Lucherini, and Imre Takács, eds, The Art of Medieval Hungary (Roma: Viella, 2018) (Bibliotheca Academiae Hungariae – Roma, Studia 7).

The explanation for my courage is, in fact, twofold. On the one hand, the scale of this collaborative project involving all professionals in this field is demonstrated by the fact that virtually everyone qualified to present it actually participated in the project. On the other hand, as director of the Hungarian Academy in Rome between 2011 and 2016, and as editor of the series in which this volume was published, I was exceptionally fortunate to have had the opportunity to take part in the work from the time of its conception. This, of course, determines the approach of this article to a significant extent. My review will not include either an art historian’s strict criticism concerning possible gaps or withering comments on disputed assignment of dates and dubious attributions; rather it will include subjective thoughts on what this book and the road which led to it mean to me personally, since I fully subscribe to the approach proposed in the book’s introductory article by the editor-in-chief, Xavier Barral i Altet, one of the doyens in the field of the history of European medieval art: the driving forces of historiography can be grasped, mostly, in the biographical background of the authors. Contemporary methodological approaches of historiography assign an important role to personal motivations, encounters, and social networks in the study of the development of themes and the genesis of works. Our book is no exception to the rule, so the reflections thereon are, perhaps, not unnecessary.

The story began in the autumn of 2011, during the months following my arrival in Rome. In the course of the usual introductory meetings, I was visited by a Czech academician, Jaroslav Pánek, the director of the Czech Historical Institute in Rome, and I showed him around the seat of our Academy, the Palazzo Falconieri, designed by Francesco Borromini. At the end of his visit, we went up to the terrace on the roof of the loggia, which offered a magnificent view of the Eternal City. The magic of it is due to the fact that one can admire the full panorama of the city, right from its centre, and one gets the feeling that the entire Urbis is spread out at one’s feet: Rome, the patria communis, Europe condensed, Europe on a smaller scale. There, on the roof terrace of the palazzo, we can really feel, for a moment, that we are standing on top of Europe, with a clear view of the entire continent, and we can also place ourselves in it. These were the ideas swirling in my head when professor Pánek turned to me and said that we, Hungarians in Rome, with this wonderful Baroque palace and our Academy with a great past, are not a small nation at all, but are on par with the greatest nations, and our historical mission is to assume a leading role in the science and culture of Central Europe. The comments and encouragements of my Czech colleague convinced me that we—at least in Rome—should have the courage to be big, and to dream big in the limited period of time I had ahead of me in the city.

Dreams, however, only come true if we learn and keep the rules which are indispensable for their successful realization. The most important guideline is that our past can only be placed effectively in an international environment if we present it in a European context. Against the backdrop of Rome, we can only put ourselves on the map with subjects that are suitable for Central European and European comparative historical study, and also have an Italian and Roman relevance. At the same time, these subjects should have some novelty from a historiographical perspective, and should be in the focus of current research efforts. We as a scholarly institution of a Central European nation only have a chance in the crowded milieu of national academies in Rome to stir any real interest among international scholars if we take all of these factors into consideration. Another key point is that we should only appear on the best and most prestigious forums, with an autonomous series of books from our institute, since the publisher itself positions the publication. With this objective in mind, I contacted Viella, the most dynamic publisher of historiographical works in Rome, also known in the English-language market, which, along with Italian (primarily Roman) universities, publishes, among other things, the Italian series of the German Historical Institute in Rome. In our re-started series (Bibliotheca Academiae Hungariae – Roma, Studia), we published collections of essays and the proceedings of our conferences which were also of interest from a Central European perspective, and were clearly in the focus of interest of Roman and international historical research. Our first volume examined the links between the Catholic Church and communism, followed by books on the rule of the Angevin kings in Hungary, the advance of the Observant Franciscans in Italy and Hungary, the Eastern policies of the Vatican, and the church buildings and institutions in Rome maintained by nations on the peripheries of Catholic Europe. 3András Fejérdy, ed., La Chiesa cattolica dell’Europa centro-orientale di fronte al comunismo. Atteggiamenti, strategie, tattiche (Roma: Viella, 2013) (Biblioteca Academiae Hungariae – Roma, Studia 2); Enikő Csukovitsed., L’Ungheria angioina (Roma: Viella, 2013) (Biblioteca Academiae Hungariae – Roma, Studia 3); Francesca Bartolacci, and Roberto Lambertini, eds, ‘Osservanza francescana e cultura tra Quattrocento e primo Cinquecento: Italia e Ungheria a confronto’, Atti del Convegno Macerata–Sarnano, 6–7 dicembre 2013 (Roma: Viella, 2014) (Bibliotheca Academiae Hungariae – Roma, Studia 4); András Fejérdy,ed., The Vatican ‘Ostpolitik’ 1958–1978. Responsability and Witness during John XXIII and Paul VI (Roma: Viella, 2015) (Biblioteca Academiae Hungariae – Roma, Studia 5); Antal Molnár, Giovanni Pizzorusso, and Matteo Sanfilippo, eds, Chiese e nationes a Roma: dalla Scandinavia ai Balcani. Secoli XV–XVIII (Roma: Viella, 2017) (Biblioteca Academiae Hungariae – Roma, Studia 6) Our series was not an exclusive forum of publication; the content of some of the conferences we hosted was brought out by other publishers. Here I would only refer to one conference and the corresponding book, which was organized and edited, respectively, by our colleague Marianne Sághy, who passed away at a very young age. The collection of essays on pagans and Christians in late antique Rome was published by Cambridge University Press in 2016. 4Michele Renee Salzman, Marianne Sághy, and Rita Lizzi Testa,eds, Pagans and Christians in Late Antique Rome. Conflict, Competition, and Coexistence in the Fourth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016)

I launched this venture at the beginning of 2013 hoping that by doing so I would be able to create a high-standard international academic milieu around the Hungarian Academy in Rome that would ensure a solid long-term partnership for the Hungarian academic community in the Eternal City, the most international hub of culture. The results of my initiative came more quickly and proved to be more effective than expected, demonstrating the sensitivity of the academic world in Rome, which for centuries has been characterized by openness and a value-based approach. In the autumn of 2013, we had some additional inspiration thanks to another meeting. That was when Xavier Barral i Altet, a professor at the universities of Rennes and Venice, and Vinni Luccherini, a lecturer at Federico II in Naples, prompted by the recently published collection of essays on the Angevin kings of Hungary, turned to me with a quite ambitious plan, proposing that in the series of books of the Hungarian Academy in Rome, a representative collective monograph of many authors should be published on art in medieval Hungary. Although at first glance the project appeared to be extremely large-scale in the light of the resources at our disposal, convinced by professor Barral’s persuasive arguments I quickly agreed. As a result of coordination during the summer of 2014, the list of the editors of the planned book was also soon finalized. Along with Barral i Altet and Luccherini, Imre Takács, and Pál Lővei joined the team from the Hungarian side.

The reader will rightfully ask at this point, why professor Barral regarded this work as something sorely needed, or indeed indispensable. And, closely related to this, what were the specific arguments which made me say yes to the proposal almost immediately, in spite of the organizational and financial challenges? The project of compiling a synthesis is justified by the fact that it would fill a gap. Was a similarly comprehensive piece published recently in a world language on the history of medieval Hungarian art? Certainly not, we knew this, but the result of a meticulous review of historiography turned out to be more disappointing than expected: the last (and first) work that can be regarded as an effort to provide a synthesis was published ninety years ago, in French, and only covered the architecture of the Árpád era. That book was, in fact, a doctoral thesis prepared by László Gál, under the supervision of Henri Focillon, one of the best art historians at the time. 5Ladislas Gal, L’Architecture religieuse en Hongrie, du XIe au XIIIe siècle (Paris: E. Leroux, 1929). The dissertation summarized, for a French audience, the results of research conducted in the last three decades of the nineteenth century, which means that the knowledge it conveyed was considered obsolete even at the time of its publication. At the same time, it introduced a yet-unknown world to European experts, triggering a number of quite positive reviews, one of which was penned by Louis Bréhier, the renowned Byzantinist. 6Journal des Savants 1 (1931), 41–43. Subsequently, only a few—but high-quality—detailed studies were published, the most notable of which was Ernő Marosi’s book written in German on early Gothic art in Hungary. 7Ernő Marosi, Die Anfänge der Gotik in Ungarn. Esztergom in der Kunst des 12.–13. Jahrhunderts (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1984).

The extremely rich and particularly original relics of medieval art in Hungary, which had been studied by several outstanding Hungarian art historians, was in stark contrast with the under-representation of the subject in international research in the past. The results of the relevant Hungarian research had only been integrated into international art historiography to a rather limited extent, in spite of all efforts made to overcome this isolation. Hungarian art historians have a periodical published in a foreign language since 1953 (Acta Historiae Artium). From the 1990s, exhibition catalogues of a high standard have also been published, usually with summaries in foreign languages, or in bilingual format. 8Árpád Mikó and Imre Takács, eds, Pannonia Regia. Művészet a Dunántúlon 1000–1541. Kiállítási katalógus (Pannonia Regia. Transdanubian Art 1000–1541. Exhibition Catalogue) (Budapest, 1994); Imre Takács, ed., Paradisum plantavit. Bencés monostorok a középkori Magyarországon. Kiállítási katalógus (Benedictine Monasteries in Medieval Hungary. Exhibition Catalogue) (Pannonhalma, 2001); Imre Takács, ed., Sigismundus Rex et Imperator. Kunst und Kultur zur Zeit Sigismunds von Luxemburg 1387 – 1437 Austellungskatalog (Mainz, 2006). In addition to some significant studies, a number of collective urban history monographs that are also important from the angle of art history were completed over the last few years. 9Gergely Buzás, József Laszlovszky, and Orsolya Mészáros, eds, The Medieval Royal Town at Visegrád. Royal Centre, Urban Settlement, Churches (Budapest: Archeolingua, 2014); Balázs Nagy, Martyn Rady, Katalin Szende, and András Vadas, eds, Medieval Buda in Context (Leiden: Brill, 2016) All this, however, despite the respectable diligence and results, fell short of a major comprehensive work, without which our medieval art is inevitably excluded from international syntheses, and is completely missing from the palette so far. The absence of such a work and the resulting exclusion from international discourse was all the more regrettable due to the fact that research efforts over the last couple of decades presented art in medieval Hungary as a quite peculiar and fascinating world in itself. To put it another way, European colleagues had been unaware of art produced in the Kingdom of Hungary in the Middle Ages not because it was completely generic or derivative, but because we had failed to do enough to make them familiar with it.

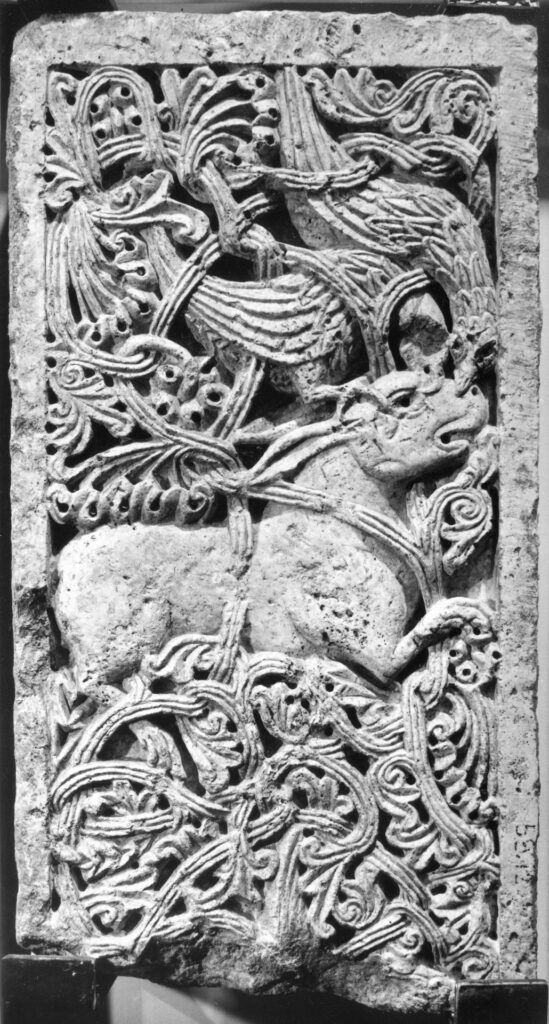

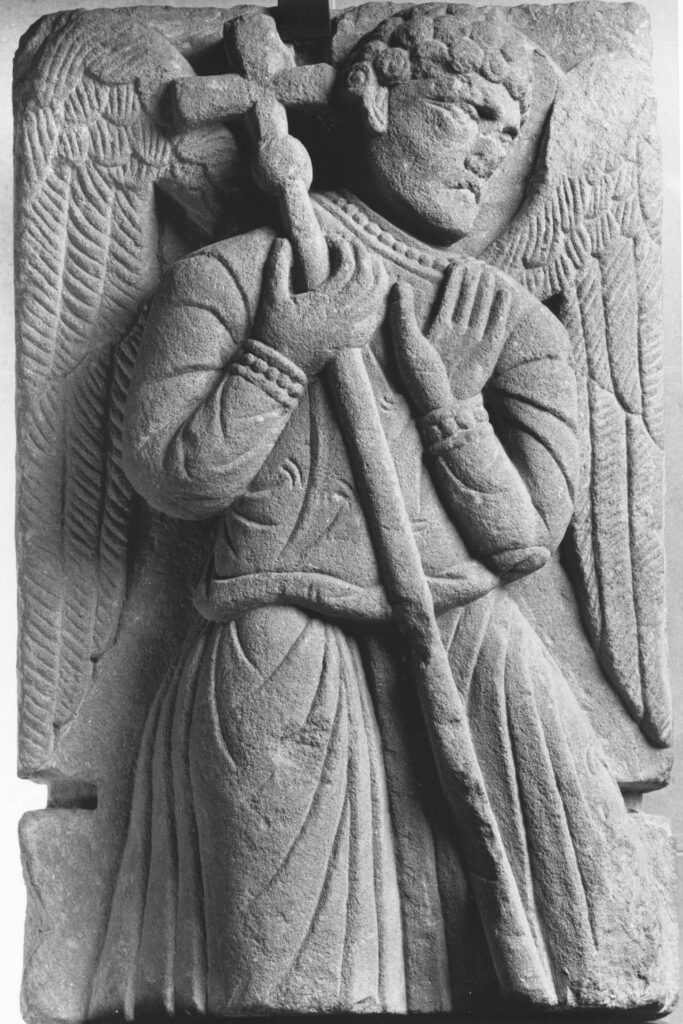

For recognizing this glaring omission, the eyes of an external party, professor Barral, proved necessary. During our conversations, a vision was outlined. He found the art of medieval Hungary singularly interesting, and worthy of international attention. In his interpretation, the Hungarian monarchy in the Middle Ages, situated in the buffer zone between the Mediterranean, the Transalpine, the Byzantine, and subsequently the Ottoman cultural realms, produced one of the most unique heritages of medieval art in Europe due to its geopolitical position as well as its weight. The Carpathian Basin was affected by uniquely diverse cultural impacts, and the artists working here responded to these impacts very creatively. The ruler of the Hungarian Kingdom and its ecclesiastical and secular elite had such financial, social, and political weight that they were in the position to order high-quality works of art. Patronage and artistic effort at the crossroads of Italian, French, German, and Byzantine art resulted in works of art of great sophistication, including the Holy Crown of Hungary, the porta speciosa in Esztergom, the Church of Ják, or the tympanum in Szentkirály. Hungarian art historians have been assessing this rich heritage since the nineteenth century, systematically and with thorough professional consciousness. A new generation also grew up after the 1980s whose research efforts meet the highest standards, and have reinvented the discipline to a considerable extent. In spite of this, their results are hardly acknowledged by European art historians. Hungary is either seriously underrepresented in compendiums of European medieval art, or is completely absent from them.

In view of the above, the large-scale synthesis which was outlined at our meetings in Rome and Budapest intended to present the most recent results of the research of Hungarian art historians for an international audience. Such works are rarely completed; our book was to be the first of its kind in history. Therefore, the team had an immense responsibility. If our efforts failed to produce a work of the expected quality, it would be impossible to publish a new version for decades to come. We had to make laser-sharp decisions on what we would like to do and how—as well as who should do it. Clearly, the editor-in-chief, professor Barral i Altet, had a key role in formulating the concept.

The first question that was posed concerned the specific subject of the book and the choice of a title to reflect it accurately. As shown by the title and the concept, the book intends to present the art produced in the territory of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. The definition of this subject does not warrant any explanation for anyone in Hungary. In international academic discourse, however, this approach is not as obvious. In contemporary art historiography, just like in the study of history as a whole, the concept of an apparently national history of art is treated with distrust due to the burden left behind by nineteenth-century nationalism. In view of international trends, the question could be rightfully raised: how legitimate is it, in the twenty-first century, to offer a synthesis of the art history of a particular period within a national framework? Art historiography, similarly to historiography, was strongly linked to nation-building in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and has thus been compromised in the theoretical discourse. The objective used to be clear enough: art historians should reveal a nation-specific art to fit the construction of the nation, especially a medieval national artistic style in line with the theory projecting the origin of nations back into the Middle Ages. This understanding of its role, of course, is not only applicable to Hungarian art historiography, but also, even more emphatically and more extended in time, to the correlation of intellectual life and nationalism in the neighbouring nation states. The will to demonstrate the existence of independent medieval Slovakian and Romanian art was stronger, and they have represented this conception more effectively in the international arena than us. The result of this is that European colleagues nurturing an aversion to Hungarian nationalism seem a lot less bothered by the idea of an autonomous medieval Slovakian art or that of the three Romanian provinces.

We defined the core concept of the book with all this in mind. It had to examine the art of the medieval Hungarian Kingdom, or that of the Carpathian Basin in the geographical sense, in its entirety, in other words, the art which evolved in the territory of this multi-ethnic but politically and administratively coherent monarchy, regardless of ethnicity and especially of the current national borders. The significance of the fact that this core concept is endorsed and represented by an editor-in-chief who is a scholar of European renown, and who is not Hungarian, should not be underestimated, as this stance represents a very serious weight of legitimation for the book and for the history of art (Hungarian and non-Hungarian alike). This is indeed expressed by the title: The Art of Medieval Hungary.

Selection of the authors for the volume required a series of informed decisions. The objective was to convey the most up-to-date knowledge currently available, and to this end, the editor-in-chief focused on the middle generation. Barral i Altet knows old Hungarian art as well as its specialists, and the twenty-four art historians contributing to the book were selected in cooperation with the Hungarian editors. Although I did not calculate their average age, it is certainly below fifty. Great figures such as Ernő Marosi had to be included, naturally, but the best and brightest of the generation under forty also had the opportunity to contribute. The participating experts represent different schools of scholarship in a balanced way, including research institutes of the academy, universities, and museums. Even though the objective was to provide a synthesis representing research efforts in Hungary, this did not mean that we had recourse only to Hungarian scholars: we had two foreign editors (Catalan and Italian), as well as a German (Evelin Wetter) and a Slovakian author (Ivan Gerát).

While the medieval state of Hungary constituted the frame of reference, the cornerstones of the concept included a strong emphasis on the Europeanness of medieval art in Hungary. As is pointed out by the editor-in-chief in the introduction, our art before 1526—regardless of the Finno-Ugric linguistic relatedness, and, let us also add, the eastern/steppe/Turkic relation—was entirely part of the civilization of the West: all elements of Romanesque and Gothic art in Hungary are connected with Western European art. It means that the most spectacular proof, palpable also today, of our belonging to Europe and its Western half is our art. As such, it deserves an eminent place in all summaries of the history of European art, which it currently fails to occupy. We can facilitate the closing of this painful gap with a synthesis which presents medieval Hungarian art in its entirety, with all-encompassing surveys, showing the most important objects held in collections, in a world language and based on a concept that is interesting to and compatible with contemporary scholarship.

The book comprises three major blocks. The central section is made up of twenty comprehensive studies, followed by the presentation of twenty-one carefully selected objects of art, and an introduction of the seven most significant collections of medieval relics. All studies are presented without notes, but each is followed by a bibliography in which the author presents the relevant literature available in foreign languages. A combined bibliography and index of persons and places are also provided, specifying the current names of Hungarian settlements which are now under the authority of the neighbouring countries. The appendix of illustrations is just as rich as the texts, including 250 black-and-white figures and 94 coloured plates. This volume is a gapless synthesis, intended to serve as a comprehensive manual, with chapters prepared according to uniform editorial guidelines, presenting the entire medieval art of Hungary. The text does not follow the conventional art history chronology, structured according to the main periods (Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance) which could make it appear a dull textbook; instead, the studies are arranged into six major chapters based on threads of connectivity with Europe. Naturally, Professor Barral i Altet, who determined the centres of gravity for each chapter, was not guided by an approach based on the Hungarian national spirit, but rather by the issues and approaches with relevance to the European history of art. The starting points for the book include urban history, the history of cults and liturgies, and symbols of power, which facilitate an examination of the history of art from such a panoramic perspective of cultural history and sociology that it succeeds in creating its international context, employing the most relevant terminology. The result is something fresh and with European relevance, thanks to its angle and narrative, in addition to the facts presented in it.

The twenty comprehensive studies are arranged in six thematic blocks. The two texts of the first chapter present the historiography and the sources. Ernő Marosi’s magisterial essay provides an overview of the efforts of art historians specialized in Hungarian medieval art, presenting the political and cultural context of the evolution of the discipline, and its close connection with the emergence and development of architectural heritage protection, keeping an eye, all along, on both close and looser connections with international scholarly efforts. Kornél Szovák gives an analysis of the typology of written sources relevant to the history of art, embracing the entire spectrum of genres, from administrative texts through narrative sources to inscriptions on objects.

The second suite of studies approaches the subject from the perspective of different settlements, and discusses analyses within the framework of town and country. Katalin Szende, with a functional analysis, presents the development of Hungarian towns and cities in the context of the European network of cities, while Pál Lővei’s review of the art of medieval Hungarian towns builds on her results. The strong focus on urban space is justified by international research efforts in urban history, and it contributes to the study of Hungarian urban development and its aspects and relevance for art historiography. Zsombor Jékely’s piece is about architecture in the countryside, churches in villages, primarily, while István Feld gives an overview of fortresses, castles, and mansions in medieval Hungary.

The five studies in the third block discuss the liturgical context of architecture and the fine arts, providing a comprehensive description of ecclesiastic art in medieval Hungary. It is an important point that by positioning it next to the previous chapter, the traditional predominance of the ecclesiastic aspects in the works of art historians of the Middle Ages is complemented. Béla Zsolt Szakács discusses Romanesque architecture, with special regard to the personages promoting it, along with their social status and motivations. Krisztina Havasi focuses on establishing the European connections of sculpture in Hungary in that era. Imre Takács presents architecture and art in the early Gothic period, and in his study co-authored with Lővei, the late Gothic period, the period of the Angevin kings in Hungary, is organically connected with the Trecento in Italy. The picture is completed by Gábor Endrődi’s piece on winged altarpieces, a separate study warranted by the rich body of surviving artefacts of this kind. According to Endrődi, their production can be traced back to links of trade with Southern Germany, and the social and economic impact thereof.

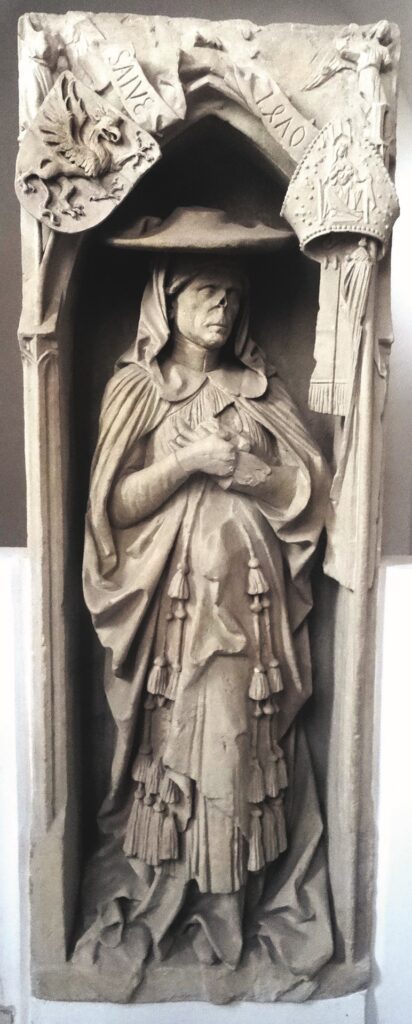

The three articles in the fourth major chapter take the reader to the world of religious cults and symbols of power. Here the authors move away from the conventional framework of interpretation of art historiography in a strict sense and use the latest methods applied in European research: they interpret the symbolic functions which the commissioning patrons wanted the artworks to convey. Gábor Klaniczay, one of the top scholars studying the sanctity surrounding European monarchs, explores the last thirty years of research in hagiography in Hungary. Vinni Luccherini introduces the symbols of power of Angevin rulers and the rhetorical and political functions of artworks by a thorough analysis of the Holy Crown and The Illuminated Chronicle. Pál Lővei discusses tombs and their inscriptions, magisterially summing up three decades of research into epigraphic relics. The significance of this unit of the book is demonstrated by the fact that the image on the cover, as requested by the editor-in-chief, is associated with it. The same image was displayed on the cover of the catalogue of the memorable Pannonia regia exhibition, showing the large seal of the Esztergom chapter, from the beginning of the 1320s. A point of interest of the seal is that it does not feature Saint Adalbert, the patron of the basilica, but the Archbishop of Esztergom who crowned the sovereign, Charles Robert, which is a unique manifestation of the representation of a European ruler’s sovereignty.

The two articles under the fifth chapter, going beyond the sacral–secular dichotomy, survey artwork intended for public and private use. Evelin Wetter presents jewellery and textiles, and Anna Boreczky discusses books. In spite of their usually high rate of destruction, the body of artwork surviving to this day in Hungary is significant by European standards in all three categories, but especially in those of jewellery and books.

Finally, the three essays in the sixth block explore how the Middle Ages lived on. Within the conceptual framework of the book, the end of the Middle Ages is marked by the rule of Emperor Sigismund. With this decision, the editors joined the trend in European art historiography which maintains that medieval art ended with the Trecento, while the Quattrocento was already the beginning of a new period, from which point the development of European culture can be described as essentially linear. According to Imre Takács, art under Sigismund reflects the decline of the Middle Ages (or the dawn of the Modern Era). Let me quote just one example. Sigismund’s propaganda already followed patterns that could be considered modern, with the ruler’s portraits as one of its most characteristic manifestation. Thus the Hungarian Renaissance can be called a dream (see Árpád Mikó’s essay), confined to the royal and a few ecclesiastical courts, lacking a solid foundation, and remaining without significant continuation. The significance of the all’antica art in King Matthias’s court lies in its uniqueness, as it is pointed out by Árpád Mikó. The closing study is connected with the first one, completing the circle: Gábor György Papp explores how the Middle Ages lived on in nineteenth-century architecture, stressing the symbolic significance of references made to the medieval Kingdom of Hungary in shaping Hungarian national identity in the nineteenth century.

The second major structural unit, Appendix I, presents twenty-one artworks, the result of a carefully targeted, well-considered selection process, with the primary objective of offering a representative set of artefacts which illustrate the evolution of medieval art phenomena in Hungary and the relationships analysed in the comprehensive essays. Accordingly, the majority of the contributors here were selected from among the authors of the essays in the first part, together with Szilárd Papp, Ivan Gerát, and Péter Farbaky. These shorter articles, in no more than four pages on average, describe our two coronation insignia, the mantle and the Holy Crown, thirteen buildings including sacral and secular centres as well as monasteries (Tihany, Székesfehérvár, Esztergom, Buda, Gyulafehérvár, Lébény, Ják, Siklós, Visegrád, and Vajdahunyad), the Gothic statues of the Royal Palace of Buda, the altar in Kassa, the sepulchral monument of Saint Margaret, the Angevin Legendary, and The Illuminated Chronicle. In Appendix II, seven public collections are introduced by the authors (Piroska Biczó, Györgyi Poszler, Emese Sarkadi Nagy, and Ágnes Ziegler-Bálint, in addition to those already mentioned): the Hungarian National Museum, the Old Hungarian Collection of the Hungarian National Gallery, the Christian Museum of Esztergom, the Treasury of Esztergom Cathedral, the Budapest History Museum, the Brukenthal Museum in Nagyszeben, and the collections of stone carvings (lapidaries) in Hungary.

Now, towards the end, let me go back to the starting point, the story of how this book was conceived and executed. When the concept was finalized in the winter of 2014 and 2015, it became obvious for all of us that our venture was truly special, since with the synthesis we were about to provide, Hungarian art historiography, thereby Hungarian humanities, and in fact the position of Hungary within Europe (its national image) could take several steps forward. We can make up for the default of several generations—and do a lot more than that. The editors’ enthusiasm was contagious. Only three of the authors requested to contribute were unable to make a commitment, and the twenty-four contributing authors completed their essays in record time. Almost all of them gave us completely new texts, as requested by the editors; instead of earlier articles dusted off and patched up, we received synthetic new articles intended for an international audience.

We all know that the attic is filled with great ideas and enthusiasm, but fortunately our ambitious plan was immediately embraced by Pál Fodor, the director general of the Research Centre for the Humanities of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and the project was added to its large-scale programme of publications in English. With Fodor’s support and the funding of the Hungarian National Bank, the book was out by the autumn of 2018. The careful and thorough work of the publisher in Rome, Viella, should also be noted; they took all our requests into account, and implemented them at a very high level of quality. Cecilia Palombelli and her team are eminent representatives of that very ambitious and generous editorial and publishing ethos which is becoming increasingly rare both in Europe and overseas.

What does the story of this book prove for me, for us? It proves, first of all, that if we want to present, outside our borders, a part of our past closely connected with and significantly enriching European history, then we can find serious allies among our colleagues abroad. In 2013, a renowned scholar who is European from head to toe (in terms of attitude and authority), one of the top researchers of medieval art in Europe, offered to help his Hungarian colleagues with the aim of introducing the treasures of medieval Hungarian art to an international audience. The reason for this was that what survived from art produced in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary is unique, interesting, and valuable from a European perspective. And this means that our heritage—mostly destroyed, standing over the ruins of which we usually grieve and feel ashamed, and rarely believe anyone on the other side of our western border could be interested in—is considerable and far from uninteresting for those who know what to look for in what was left from medieval art in Europe. The essence of Europe consists of learning and creatively adapting one another’s cultures. It is not a one-way reception and making copies with a servile and provincial shoddiness, but a constant cultural interaction to which Central Europe and Hungary made their own contributions. Hungarian historians are faced with the task of presenting this process in a language compatible with European scholarship—that is the task we were asked to fulfil, with the friendly encouragement of Professor Barral i Altet.

Another aspect of the experience was that for this national cause, members of the Hungarian community of experts in this field were also willing and able to join forces in an exemplary way. As the editor-in-chief highlights in his introductory article, this book would not have seen the light of day without networks and intellectual friendships of scholars similar to what our humanist predecessors once operated throughout Europe. If we fail to realize this, we will not understand the genesis and execution of this book either. And this explains how it was possible for this multi-author venture to be realized so smoothly, without the slightest of conflicts. One might even say, if it was not a blasphemy in the light of all the hard work that went into it, that it all just happened by itself. To put it another way, without joining forces and thinking together, we can only cover a much shorter distance with a lot more effort.

And finally, for me, the main lesson of producing this book matches exactly the most important experiences I have had in the last few years. Rome teaches us to dare not to be small, in the non-physical sense. Doing away with defeatism and narrow-mindedness, we should boldly show the world what we can be proud of, and we should not give up what is ours because then we might lose it for good. I started out with the Borromini loggia, so let me finish on the same spot, on the roof terrace. If we look at the city of Rome from above, we can see Europe below us: the French, German, and Spanish institutes, the churches of different nations, the ancient cradle of European culture. Every Hungarian who has come to Rome and climbed up to this terrace has said they felt at home here. This hefty volume is a massive brick in the wall of our shared home—and homeland—in the spiritual sense. Whoever flicks through it or reads it carefully, be it a Hungarian or a European compatriot, will certainly get a sense of the common culture we all share.

The photos of the article are reproduced with kind permission of Pál Lővei and Imre Takács.

- 1This text is the edited version of the presentation delivered at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences on 29 November 2018, the Day of Hungarian Science.

- 2Xavier Barral i Altet, Pál Lővei, Vinni Lucherini, and Imre Takács, eds, The Art of Medieval Hungary (Roma: Viella, 2018) (Bibliotheca Academiae Hungariae – Roma, Studia 7).

- 3András Fejérdy, ed., La Chiesa cattolica dell’Europa centro-orientale di fronte al comunismo. Atteggiamenti, strategie, tattiche (Roma: Viella, 2013) (Biblioteca Academiae Hungariae – Roma, Studia 2); Enikő Csukovitsed., L’Ungheria angioina (Roma: Viella, 2013) (Biblioteca Academiae Hungariae – Roma, Studia 3); Francesca Bartolacci, and Roberto Lambertini, eds, ‘Osservanza francescana e cultura tra Quattrocento e primo Cinquecento: Italia e Ungheria a confronto’, Atti del Convegno Macerata–Sarnano, 6–7 dicembre 2013 (Roma: Viella, 2014) (Bibliotheca Academiae Hungariae – Roma, Studia 4); András Fejérdy,ed., The Vatican ‘Ostpolitik’ 1958–1978. Responsability and Witness during John XXIII and Paul VI (Roma: Viella, 2015) (Biblioteca Academiae Hungariae – Roma, Studia 5); Antal Molnár, Giovanni Pizzorusso, and Matteo Sanfilippo, eds, Chiese e nationes a Roma: dalla Scandinavia ai Balcani. Secoli XV–XVIII (Roma: Viella, 2017) (Biblioteca Academiae Hungariae – Roma, Studia 6)

- 4Michele Renee Salzman, Marianne Sághy, and Rita Lizzi Testa,eds, Pagans and Christians in Late Antique Rome. Conflict, Competition, and Coexistence in the Fourth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016)

- 5Ladislas Gal, L’Architecture religieuse en Hongrie, du XIe au XIIIe siècle (Paris: E. Leroux, 1929).

- 6Journal des Savants 1 (1931), 41–43.

- 7Ernő Marosi, Die Anfänge der Gotik in Ungarn. Esztergom in der Kunst des 12.–13. Jahrhunderts (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1984).

- 8Árpád Mikó and Imre Takács, eds, Pannonia Regia. Művészet a Dunántúlon 1000–1541. Kiállítási katalógus (Pannonia Regia. Transdanubian Art 1000–1541. Exhibition Catalogue) (Budapest, 1994); Imre Takács, ed., Paradisum plantavit. Bencés monostorok a középkori Magyarországon. Kiállítási katalógus (Benedictine Monasteries in Medieval Hungary. Exhibition Catalogue) (Pannonhalma, 2001); Imre Takács, ed., Sigismundus Rex et Imperator. Kunst und Kultur zur Zeit Sigismunds von Luxemburg 1387 – 1437 Austellungskatalog (Mainz, 2006).

- 9Gergely Buzás, József Laszlovszky, and Orsolya Mészáros, eds, The Medieval Royal Town at Visegrád. Royal Centre, Urban Settlement, Churches (Budapest: Archeolingua, 2014); Balázs Nagy, Martyn Rady, Katalin Szende, and András Vadas, eds, Medieval Buda in Context (Leiden: Brill, 2016)